by Esther Morgan-Ellis

This article was written by Esther Morgan-Ellis and published in Accessible Appalachia: An Open-Access Introduction to Appalachian Studies, edited by Lisa Day. The original chapters in Accessible Appalachia are openly licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license and are freely available for reuse or adoption. Ballad of America, Inc. added images, audio examples, and playlists to the original work for publication on this page.

Contents

Introduction

In 2021 in my Music in Appalachia class, I asked students, "When you hear the phrase 'Appalachian music,' what comes to mind?" Their responses reflected old-fashioned notions and cultural stereotypes. One student described “twangy guitar or banjo accompanying lyrics about alcohol, cheating women, and ‘working for the man.’” Another imagined “a group of old men sitting around on the porch of a mountain cabin, strumming guitars and picking banjos.” “The singer will sing in a thick Southern accent,” wrote another, accompanied by “a variety of string instruments such as the fiddle, banjo, guitar, and mandolin.” According to another student, Appalachian music consists of “lots of bluegrass, ballads, hymns, and jigs being played to the delight and enjoyment of the crowd as the lightning bugs glide lazily to the tunes.”

Every student had a clear impression of “Appalachian music,” and in addition to types of singers and songs, they all agreed about its general characteristics: “Appalachian music” is communal, meant to be shared by family and friends; it is recreational and informal, performed by amateurs for their own entertainment; it is acoustic, relying on plucked and bowed string instruments; and it is closely tied to its rural mountain setting. However, my students were also keenly aware of how their impressions had been influenced by mass media. One provided a long list of films—Sergeant York (1941), October Sky (1999), Songcatcher (2000), O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), and Cold Mountain (2003)—that have shaped her ideas about Appalachian life and culture. Others described their experiences with Appalachian music from watching television, reading novels, and attending festivals.

As is the case with most popular stereotypes, my students' ideas about Appalachian music are not wrong. However, they are incomplete. While the sorrowful balladeer and front-porch banjo picker have their place in the story of Appalachian music, theirs is only one chapter in a complex and still-developing narrative. But how did the popular notion of “Appalachian music” come to exist in the first place? Although mass media plays a large role in perpetuating narratives today, people living outside of the Appalachian region have been shaping, defining, and publicizing a narrow concept of “Appalachian music” for well over a century. These people have included educators, record company executives, scholars, tourism officials, and musicians, and they have been driven by diverse and conflicting motivations. As a result, the idea of “Appalachian music” has proven to be highly malleable, changing with the goals and ideologies of the artists who make use of it.

Ballad Hunting

Before the Civil War, most Americans had no interest in Appalachian life. Indeed, the concept of “Appalachia” as a distinct cultural region did not even exist. Between 1870 and 1890, however, local color writers introduced the general public to life in the mountains by means of travel sketches and short stories.1 Early accounts portrayed mountaineers as simple and lazy—out of step with modern life, but essentially harmless. In the 1890s, however, narratives that focused on moonshining and feuding suggested that Appalachian society should be viewed as a threat, while mountain dwellers should be abhorred as primitive and dangerous.2 Such people could not possibly possess cultural practices of any value, and it is hardly surprising that their music was ridiculed or ignored. However, the public perception of Appalachia shifted yet again with the writings of William Goodell Frost, who served as president of Berea College in Kentucky from 1892 to 1920. Frost—who came to Berea from Ohio—regarded mountaineers as descendants of the noble Americans who had fought in the Revolutionary War, and he believed that they preserved important music and craft traditions.3 In his most famous essay, published in 1899, Frost described Appalachians as “our contemporary ancestors,” thereby capturing in a single phrase the idea that mountaineers preserved the genetics, manners, speech, and songs of the nation’s Anglo-Saxon founders.4

Although Frost was only tangentially interested in music, his new characterization of the Appalachian region caught the attention of early folklorists, who had just begun the project of documenting rural American cultural practices. In the Appalachians, collectors, or “ballad hunters,” set about searching for musical artifacts that would link mountaineers to their British forebears—evidence, in fact, that they were indeed “our contemporary ancestors.” Specifically, collectors were looking for ballads: unaccompanied songs in which verses telling a story were sung to a simple melody.5 Interest in British ballads had first been piqued by Harvard rhetoric professor Francis James Child, who scoured ancient manuscripts for ballad texts for inclusion in his ten-volume magnum opus The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, published between 1882 and 1898. As a result, collectors were most eager to find living representations of what were termed “Child ballads.” Their work was supported by universities and folk song societies, and new discoveries were published in the Journal of American Folklore. As the ballad craze intensified, collectors became engaged in fierce turf wars, concealing the identity of their informants and rushing their finds into print before they could be scooped.6

Most ballad collectors had no interest in the lives or futures of their informants, regarding them merely as imperfect vessels bearing timeless musical artifacts. The role of the collector was to “rescue” these artifacts from destruction. However, the most influential collectors were those who lived and worked in the mountains—in particular, the women who founded and operated settlement schools. The settlement school movement had begun in England, and its mission was to educate and uplift working-class youth. Although the first settlement schools were urban, early 20th-century reformers—inspired in part by Frost’s call to serve the educational needs of “mountain whites”—opened institutions throughout the Appalachians. Settlement workers both collected ballads themselves and hosted visiting collectors, thereby providing access to what had become a much sought-after natural resource.7 However, they did something else that was of even greater significance: They integrated ballad singing into school curricula and encouraged students to recall old ballads and learn new ones. As a result, ballad singing became more common and gained prominence in Appalachian life.8 Settlement women performed other acts of cultural intervention as well. They discouraged fiddle and banjo music, which they associated with Saturday night carousing, and instead encouraged mountaineers to build and play the mountain dulcimer, a plucked string instrument held on the lap. As a result, the mountain dulcimer—previously unknown in most parts of the Appalachians—came to be widespread, and was adopted by influential ambassadors of Appalachian music.

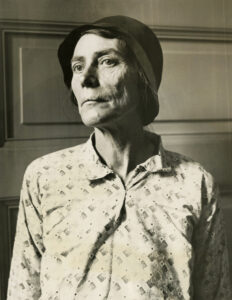

Settlements also played a key role in the most significant ballad collecting expedition, undertaken by Olive Dame Campbell (1882-1954) and Cecil Sharp (1859-1924) in 1916. Campbell first toured Appalachia in the company of her husband, who had been engaged to conduct a social survey of mountain life. In 1908, she visited the Hindman Settlement School in Knott County, Kentucky, where co-founder Katherine Pettit had been collecting ballads since the school opened in 1902. Pettit arranged for a student to sing the Child ballad “Barbara Allen” for Campbell, who found herself overcome by the music; she later described the performance as “so strange, so remote, so thrilling.”9 Campbell set out on her own collecting project, quickly amassing a library of ballads, and in 1916 she convinced the famous English ballad expert Cecil Sharp to visit Southern Appalachia. The two of them began their collecting expedition at Hindman, where Sharp, too, was entranced by the children’s singing. They subsequently spent nine weeks recording ballad texts and tunes in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, publishing their finds as English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians in 1917.10 Sharp would undertake several additional expeditions over the next two years, and it was his scholarly stature that established ballads as the first significant exemplar of “Appalachian music.”

Jean Ritchie "Barbara Allen"

When Sharp went into the mountains, he was explicitly searching for remnants of British musical traditions. He believed that the isolation of Appalachian mountain life had preserved ballads just as they had been sung centuries earlier in the British Isles, and that the versions he collected in the United States were therefore the most “authentic” in existence. Sharp’s mission, however, was extremely narrow, and he turned away all musical practices other than unaccompanied ballad singing. He described the difficulty of convincing his informants to sing anything other than hymns, and lamented the influence of popular songs, which found their way into the lives of mountaineers via phonograph recordings and traveling performers. He also ignored instrumental music, commenting only briefly on the guitar, fiddle, and mountain dulcimer.11 Finally, and perhaps most significantly, he collected exclusively from White informants, despite the fact that Black residents made up 13.4% of the mountain population in 1910. By doing so, he helped to establish the persistent myth that Appalachian music is exclusively the music of White people.12

The Birth of "Hillbilly" Records

The myth of “hillbilly” music was reinforced in the 1920s, when record companies discovered the commercial potential of Appalachian music. In 1923, Ralph Peer—recording director at Okeh Records—traveled to Atlanta to capture the playing of local musician Fiddlin’ John Carson. He came at the behest of an Atlanta phonograph retailer, who felt sure that there would be a market for Carson’s recordings.13 Carson himself was something of a local legend; he was a perennial favorite at the annual Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Convention and could attract a crowd anywhere in the city.14 Although Peer personally found Carson’s records abhorrent, the first thousand sold almost immediately. Clearly, there was money to be made from rural styles and repertoires.

Fiddlin' John Carson "The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane"

The discovery of Carson followed closely on the heels of the first recordings of Black performers, which had likewise proved commercially successful. In 1920, Okeh’s recording of Mamie Smith singing “Crazy Blues” birthed an entire new marketing category: “race” records. Imitators soon flooded the market with recordings of Black blues singers, who were often promoted as being more authentic than their White counterparts.15

Mamie Smith "Crazy Blues"

When Peer began to record rural White musicians, he again declined to list their releases in Okeh’s general catalog, surmising that rural records would have only niche appeal. To accommodate performers like Carson, therefore, the category of “hillbilly” records was invented.

The designations of “race” and “hillbilly,” like musical genres today, were marketing categories, designed to connect consumers with music that they could expect to enjoy. However, these categories did not reflect actual musical practice, which was not divided neatly across racial lines. Just as White musicians often sang the blues, Black performers played fiddle and banjo, formed string bands, and sang sentimental songs. Indeed, Black fiddlers were foundational in the development of Appalachian playing styles, and the banjo is an Afro-Caribbean instrument.

Black string band Gribble, Lusk, and York "Rolling River: Country Dance"

Unfortunately, the new categories determined which performers were allowed to record which types of music. Black musicians were often recorded only if they were willing to perform styles of music associated with the Black community—namely, blues and jazz. White musicians were given greater latitude, although they, too, had to accommodate stereotypes in a bid for commercial appeal. The Skillet Lickers, a string band from North Georgia who made their first record in 1924, serve as a prime example. Bandleader Gid Tanner was always willing to put on a “rube” act to win applause, and many of the band’s records contain skits portraying comical scenes of mountain life; even the band’s name was meant to evoke the hillbilly stereotype.16 However, these performers were at least able to make a living. Black musicians who played “hillbilly” music were usually turned away by record company representatives.17

Gid Tanner & His Skillet Lickers "Hen Cackle"

“Hillbilly” music was not necessarily Appalachian music, but the music of White mountaineers certainly qualified as “hillbilly,” and a large number of mountain musicians sought out careers as hillbilly recording artists. At the same time, Appalachia and the hillbilly stereotype were inextricably bound together in the imaginations of many Americans, such that hillbilly records were perceived as the soundtrack of mountain life. The segregation of rural musicians into “race” and “hillbilly” categories, however, meant that the music of Black Americans was excluded from the emerging Appalachian soundscape. By necessity, social constructions of music genres said that if music was “Black,” it could not also be “Appalachian.”

White Appalachian musicians could also find employment and publicity on hillbilly radio programs. In 1923, the first “barn dance” program was broadcast out of Fort Worth, Texas, and the model was firmly established in 1924 by National Barn Dance, which could be heard across much of the United States and Canada. Significantly, however, National Barn Dance broadcast not out of Appalachia, or even the South, but out of Chicago. Founder Edgar L. Bill anticipated that urban Americans, disillusioned by modern city life, would find solace in the nostalgic sounds of rural music. He was also responding to the influx of rural Southerners who came to the Midwest looking for work. These migrants—who included Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass—brought their musical tastes and abilities, providing both an audience and a talent base for hillbilly music.18

The Monroe Brothers "New River Train"

In 1925, National Barn Dance announcer George D. Hay moved to Nashville and founded The Grand Ole Opry, which would go on to become the most famous and influential country radio (and later television) program in the nation. Appalachian musicians could also find employment on local radio programs, although traveling between stations to satisfy a demanding schedule of live broadcasts was exhausting work.19 In all cases, hillbilly radio served to further cement the racial divide and establish Appalachian music as White and Anglo-centric.

The Rise of Folk Festivals

While the 1920s saw the popularization of Appalachian musical styles by means of commercial recordings and radio programs, the 1930s witnessed a reaction against these forces. Many folklorists and collectors were horrified by the entrance of Appalachian performers into the world of mainstream commercial music. They feared that commercial forces would warp and contaminate pure folk culture, and they dismissed hillbilly records as inauthentic and crass. In an effort to stem the flood of commercial folk representations, advocates of “genuine” folk music established festivals for the purpose of encouraging the preservation of what they believed to be the finest and most authentic folk practices. The specific motivations and goals of each festival organizer, however, were unique, as were the limits they placed on the concept of “Appalachian music.”

The first folk festival—not just in Appalachia, but in the entire United States—was founded by Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973), a native of Madison County, North Carolina. Lunsford was well-educated, eventually earning a law degree, but his fascination with rural music and dance kept him in the area, and he dedicated most of his time to seeking out local musicians in order to learn their tunes and songs. He undertook several formal collecting expeditions, touring the mountains with Robert W. Gordon, the first head of the Library of Congress Archive of Folk Song, in 1925, and with Dorothy Scarborough of Columbia University in 1930. A musician himself, Lunsford also recorded hundreds of traditional songs for Columbia Records and the Library of Congress.220 As a member of what Appalachian music scholar David Whisnant has termed the “bi-cultural elite,” Lunsford had access to institutions and funding networks, yet also identified with his sources. He held a deep respect for Appalachian people and culture, and he fought against hillbilly stereotypes throughout his career.21

Bascom Lamar Lunsford "Old Mountain Dew"

In 1928, Lunsford was invited by the Chamber of Commerce in Asheville, North Carolina, to contribute a program of music and dance to the first annual Rhododendron Festival. The object of the festival, which constituted a small part of a broader advertising campaign, was to promote tourism and boost local businesses, and overall it was a highly artificial affair. Lunsford’s evening of regional music and dance was one of few events that reflected local culture, but it also proved to be extremely popular: About five thousand spectators crowded into Pack Square to watch groups of square dancers compete for cash prizes to the accompaniment of string band music.22 The program also included fiddlers, string bands, and singers, each hand-picked and presented to the spectators by Lunsford himself. In 1930, Lunsford left the Rhododendron Festival behind to found Asheville’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival.

Competition was at the heart of Lunsford’s festival design. This approach had a practical benefit: Lunsford did not pay most of his performers, so cash prizes were necessary to lure skilled participants. Although there was a history of fiddle contests in the region, Lunsford’s model was novel in many ways. Square dancing had not previously been presented in a concert setting, and there was also no precedent for competitive dancing (other than the informal buck-dancing duels that might take place at square dances in private homes). As a result, Lunsford’s festival changed local practices. Dancers began introducing buck-dance steps into the square-dance patterns, and they abandoned street clothes in favor of coordinated uniforms. Within a generation, locals were more likely to participate in formal square-dance teams than to attend the private house dances of Lunsford’s youth. The potential rewards for becoming an accomplished square dancer, however, extended beyond prizes and local celebrity. As folk culture gained national cachet, polished practitioners gained access to meaningful career paths and elite sponsorship—a new reality exemplified by Lunsford’s 1939 White House presentation of square dancing for no less an audience than the President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and Great Britain’s King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.23

From Our House to the White House: Mountain Square Dancing in the 1920s - 1930s

Lunsford’s intervention transformed the practice of Appalachian square dancing while simultaneously elevating it to the level of national culture. He also shaped the contents and character of Appalachian instrumental music. While traveling the countryside seeking out possible festival performers, he would give advice to developing musicians, thereby influencing their future repertoire and style. He strictly controlled the material presented on stage, forbidding overt references to alcohol and sex. He also required that performers dress according to his standards, rejecting both hillbilly garb and the “revealing” clothes of the modern woman. As a result, Lunsford’s Appalachian music was significantly more chaste than what might be encountered outside of the festival. Finally, although Lunsford collected music from Black informants and reportedly spoke well of them as individuals and performers, no Black musicians ever took the stage while he led the festival.24

Lunsford’s festival served as an important model for others. In 1934, Sarah Gertrude Knott (1895-1984)—a relative outsider with no real background in Appalachian music—would take the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival as the model for her National Folk Festival. Although Knott sought to recruit performers from diverse traditions, the music of White mountaineers occupied a central role in her efforts; it had come, after all, to stand in for “American” folk music. Lunsford himself brought a contingent of square dancers to participate in Knott’s inaugural event, and he also facilitated some of the regional festivals that were established for the purpose of selecting the finest representatives of each tradition. The artists’ participation had to be subsidized by local arts councils or business leaders; like Lunsford, Knott did not pay performers. Although the regional festivals were not staged as competitions, the fact that only a few local artists would be invited to participate in the National Folk Festival led participants to carefully curate their presentations. The incentive of a national stage encouraged hopefuls to revive forgotten songs and purge popular influence from their performance styles. As a result, Knott and her collaborators—like Lunsford—changed the practices of folk musicians just as they sought to preserve them.25

Knott incorporated diverse performers and traditions into her festival from the start. Indeed, the Black novelist Zora Neale Hurston was one of her first collaborators, participating in the 1934 festival and later serving on the festival board, while the inaugural event opened with music and dance by members of the Kiowa tribe of Oklahoma.26

Kiowa Tribe "Kiowa Gourd Dance"

The same cannot be said of the decade’s other prominent folk festival, the White Top Festival, which took place annually in Grayson County, Virginia, from 1931 until 1939. Although it lacked the staying power of Lunsford and Knott’s festivals, both of which persist into the present day, the White Top Festival was significant and influential while it lasted. It also embodied a darker side of the 1930s-era folk revival.

The White Top Festival began as little more than a fiddlers’ contest, although the organizers had loftier aims for their endeavor. All three of the festival’s architects belonged to the social elite: John Blakemore, who first fielded the idea for a contest, was an attorney; Annabel Morris Buchanan, who did most of the organizational work, was a clubwoman who had long been interested in traditional music; and John Powell was a respected classical composer. From the start, they strictly limited the repertoires and styles that would be allowed into White Top. They favored solo performers over string bands, welcomed the dulcimer, barred popular compositions, and tried to eliminate all traces of the influence of hillbilly records and radio. Over the years, the organizers were successful at encouraging the music they approved of to proliferate, and when academic folklorists gathered at the 1934 festival they were able to congratulate one another on their efforts to preserve mountain culture.27

Although White Top was successful from the start, a visit by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1933 really put the festival on the map. Rumors of her appearance attracted the national press and swelled the crowds from 3,000 to as many as 20,000. Eleanor Roosevelt’s decision to attend should come as no surprise: Her husband, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had just been elected President, and it was fitting for her to take an interest in the cultural practices that were believed to represent working-class Americans.28 Roosevelt’s presence put the stamp of approval on White Top, and the festival continued to expand its offerings in the coming years, adding programs of shape-note singing, of hymns and sword, and of Morris dancing. The latter is particularly fascinating, as these archaic English dance forms had no history in Appalachia whatsoever. They had been introduced by Cecil Sharp to students at the Hindman Settlement School and had then quickly spread to other settlement and folk schools. Sword and Morris dances were regarded as companions to the ballad—the dance equivalent to the music so highly valued by collectors.29

The introduction of archaic English dance into the White Top program, however, was of great symbolic significance. It represented the organizers’ commitment to an explicitly Anglo-Saxon strain of Appalachian music. It also brought the omission of all other cultures and traditions into stark relief, for White Top explicitly barred the participation of Black musicians. This exclusion was due to the influence of John Powell, who was a committed segregationist and anti-miscegenation activist. In 1924, Powell had helped to design Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act, which defined “White” and “colored” races and prohibited any “mixing.” The Act established that a single drop of “colored” blood meant that an individual was legally “colored” and therefore subject to Jim Crow segregation ordinances.30 When Powell barred Black musicians and their traditions from White Top, he likewise sought to prevent mixing. His aim was to preserve the so-called purity of what he believed to be superior White culture.

Unfortunately, Powell was not the only prominent cultural organizer to deploy Appalachian music and dance for the purpose of upholding White supremacy. Although White Top collapsed in the second half of the decade due to a combination of bad weather and interpersonal strains, the mission to promote Anglo-Saxon folk culture as an antidote to Black influence was being carried out on other fronts. The most famous advocate of Appalachian culture to oppose racial mixing was most certainly Henry Ford, who in 1923 embarked on a well-funded campaign to promote old-time music and dance that would end only with his death in 1947. In the early 1920s, Ford established himself as the leading American anti-Jewish fear-mongerer by publishing a series of overtly antisemitic articles in the Dearborn Independent, a Michigan newspaper that he had recently purchased.31 He used the same newspaper to trumpet the virtues of the fiddle, banjo, and square dance, and he explicitly framed his revivalist efforts as an offensive against the onslaught of Black music and dance (namely, jazz). Ford had widespread influence: In addition to funding recordings and radio broadcasts, he inspired a surge of new fiddle contests and was largely responsible for the incorporation of square dancing into school curricula.32 His contributions to the folk revival, however, were driven by the belief that Appalachian culture—viewed narrowly—was a powerful tool for upholding White supremacy.

The Urban Folk Revival

The ideologies of Powell and Ford are particularly fascinating in the light of the urban folk revival, which commenced in the 1930s and gained national momentum in the 1950s and 1960s, eventually exerting a significant influence on mainstream popular music. Although all of the activities described in the previous section constituted “revivals,” they were largely confined to the South and centered in rural communities. During the Great Depression, however, urban youth with left-wing political leanings became increasingly fascinated with folk music in general and Appalachian music in particular. They viewed it as the music of the working class and believed that it was the ideal vehicle for radical political messages. Although they were often frustrated by the real-life politics of the musicians they revered, urban folk revivalists were successful in cultivating widespread interest in Appalachian music among well-educated, White, middle-class Northerners. These revivalists not only listened to recordings but adopted Appalachian musical practices as their own, playing fiddle and banjo in traditional mountain styles, singing ballads and songs as the mountaineers did, and mastering the steps of the flatfoot and buck dances.

Urban folk revivalists took a broader view of Appalachian music than those who had come before them, embracing artists and repertoire that had been rejected by the ballad collectors and festival organizers. For example, some of the first Appalachian musicians to become celebrities in folk music circles were the coal miners whose political songs had fueled the labor struggle in Harlan County, Kentucky. After participating in the so-called Harlan County War of 1931 and 1932, Aunt Molly Jackson, Jim Garland, and Sara Ogan Gunning all relocated to New York City, where they were active as performers and organizers.33 Along with Florence Reese, who remained in Kentucky, these musicians wrote new verses to traditional melodies in order to inspire members of the coal miners’ unions to action.34 Their songs concerned the harsh conditions of life in the mining camps—a far cry from the nostalgic ballads first sought by Sharp.

Jim Garland "The Death of Harry Simms"

The singers from Harlan County—especially Aunt Molly Jackson—had a significant impact on two young revivalists who would go on to shape the movement in the mid-20th century: folklorist Alan Lomax (1915-2002), who recorded the bulk of Jackson’s repertoire when he was only nineteen, and folk musician Pete Seeger (1919-2014), who met Jackson as a fifteen-year-old and transcribed many of her songs. It is worth considering the contributions of these two men in considerable detail, for they were representative of the activities and interests of urban folk revivalists as a whole.

Both men came to the study and performance of American folk music through their parents. Alan Lomax was the son of John Lomax (1867-1948), who had studied at Harvard under the ballad expert George Lyman Kittredge (himself a disciple of Francis James Child). Although John Lomax’s initial interest was in cowboy songs of the Western frontier, his fascination with American folk culture quickly broadened. In 1933, he and his son embarked on the first of many tours through the rural South for the purpose of making sound recordings. Unlike the collectors who had come before, the Lomaxes were expressly interested in documenting Black music, which they primarily sought among the incarcerated. Also novel was their commitment to recorded media. While early ballad hunters had prized the text and perhaps tune of a song as the authentic musical object, the Lomaxes believed that folk authenticity resided just as much in performance style, and their recordings preserved both songs and the unique ways in which they were rendered. In this way, the Lomaxes’ work served to move attention from artifacts (ballads, fiddle tunes) to individual musicians, who were revealed to be more than mere vessels for the preservation of culture. This shift was a significant change in thinking that would characterize the activities and values of the folk revivalists for decades to come. Alan Lomax would go on to become the most influential American folklorist of the 20th century, making countless recordings of Appalachian musicians on behalf of the Archive of Folk Song of the Library of Congress and popularizing Appalachian tunes and styles by means of live performances, recordings, books, radio broadcasts, and documentaries.35

Pete Seeger would likewise embrace a broad range of American folk styles, although much of his work was rooted in the Appalachians. His father, Charles Seeger (1886-1979), was a music scholar, while his step-mother, Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953), was a leading American composer. During the 1930s, both were employed by the U.S. Government to work on behalf of music projects funded by the New Deal, and much of their work concerned the collecting and study of folk music. Pete Seeger, who was profoundly influenced by his parents’ interests, is remembered primarily as an activist and performer. However, he did a great deal to promote and shape engagement with Appalachian music.

Pete Seeger "Old Joe Clark"

In 1948 he published the popular instruction manual How to Play the Five-String Banjo, which inspired generations of folk revivalists to pick up the instrument and master authentic Appalachian playing styles. At the same time, Seeger made his own changes to the banjo, extending the neck in order to accommodate a greater range of musical material. Seeger was also associated with the Highlander Folk School of Tennessee, where he deployed folk music in support of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. And in the mid-1960s he featured Appalachian musicians—including guitar player Doc Watson, banjo player Roscoe Holcomb, and dulcimer player Jean Ritchie—on his television program Rainbow Quest.6

Doc Watson "Shady Grove"

It was Pete Seeger’s half-brother Mike Seeger (1933-2009), however, who would set the standard for revivalist engagement with Appalachian music. In 1958, Mike Seeger joined with fellow New Yorkers John Cohen and Tom Paley (later replaced by Tracy Schwartz) to form the New Lost City Ramblers, a string band dedicated to the preservation of authentic playing styles. Seeger and his friends would study old recordings of Appalachian musicians, seeking to imitate the details of their singing and playing.37 Significantly, they embraced the hillbilly records of the 1920s, accepting them alongside field recordings as authentic folk documents.38 The Ramblers spent a great deal of time rummaging through record bins and visiting the collections at the Library of Congress long before recordings of Appalachian music were widely available.

New Lost City Ramblers "Red Rocking Chair"

A generation later, the first major commercial collection to include historical recordings of Appalachian music, the Anthology of American Folk Music, was released by Harry Smith on Folkways Records in 1952.

Buell Kazee "The Wagoner's Lad" from Anthology of American Folk Music

Soon, however, the Ramblers became discontent with mere recordings and set out to find the artists who had made them, with other revivalists following close on their heels. This turn led to the “rediscovery” of a host of rural musicians who had first been recorded in the 1920s, many of whom were presented with new opportunities to make recordings, undertake concert tours, and appear at folk festivals.39 In some cases, folk revivalists encouraged old musicians to pick up long-forgotten instruments, or even revert to more traditional styles. The folklorist Ralph Rinzler, for example, convinced Doc Watson to give up rock ’n’ roll and return to the acoustic repertoire he had played with Clarence Ashley decades earlier. The switch paid off for Watson, who became a folk music star.40 Other Appalachian musicians were discovered for the first time—most notably the fiddler Tommy Jarrell of Surry County, North Carolina, who had worked as a road grader for 41 years and never considered music as a viable career.41

Tommy Jarrell "Walking in My Sleep"

The New Lost City Ramblers did not just sell records and concert tickets. They inspired countless Americans to pick up Appalachian instruments and seek to master traditional repertoires and playing styles. This legacy resonates into the present day. The Ramblers’ efforts, however, have done more than sustain participatory engagement with Appalachian music. As well-educated, White, liberal Northerners, the Ramblers naturally inspired imitators who were essentially like them—a partial explanation for why even today the community of old-time music revivalists is for the most part racially homogenous and dominated by liberal politics. Similarly, their obsession with authenticity—direct contact with tradition-bearers, careful imitation of historical models, and reverence for tradition—has set the standard for 21st century revivalists.

Conclusion

Appalachian music is a story of increasing inclusion. While early ballad hunters ignored instrumental music, record executives eagerly sought out fiddlers and string bands. Although festival organizers excluded newly-composed songs, Appalachian songwriters had a formative influence on the early folk revival. And while collectors of all types neglected Black musical traditions for many years, those traditions were finally documented by the mid-century folk revivalists.

All the same, “Appalachian music” as a public concept is still narrowly bound and governed by long-standing stereotypes. Whole genres of music—especially Black genres, such as blues, jazz, soul, and R&B, as well as Indigenous musical practices—have been largely excluded from the mainstream narrative.42 Relatedly, Black participation in the genres that are included has long been erased, although there is reason to hope that these injustices are being rectified. Recent decades have seen a proliferation of scholarship on influential Black musicians, including studies of guitar player Arnold Shultz and fiddler William “Bill” Livers.43 Likewise, the origins of the banjo in West Africa are now thoroughly documented.44 And although not everyone reads scholarly books, many are learning from the Black fiddlers and banjo players—including Rhiannon Giddens, Earl White, and Jake Blount—who have dedicated their careers to elucidating the histories of Black Appalachian music.45

Earl White Stringband "Cottoned Eyed Joe / Happy Hollow"

The historical exclusion of marginalized musicians and practices, however, is not the only challenge in defining an inclusive and fully representative “Appalachian music.” It is all too common to locate “Appalachian music”—indeed, Appalachia as a whole—in the past, and to identify Appalachian-ness as being a historical condition. To do so, however, is to ignore the people who live in the region today and to deny the Appalachian identity of their traditions. For example, immigration from Latin America has reshaped Appalachian demographics in recent years, introducing a range of new musical practices. When will these join the ballads and fiddle tunes of Scots-Irish immigrants as representatives of “Appalachian music”? Performers and scholars are already at work establishing the Appalachian identity of music with Latine roots.46 However, there are many other contemporary musical practices—especially those that might be denigrated as “popular” or “mainstream”—that have yet to be admitted to the “Appalachian music” canon.

Modern institutions reinforce received ideas about what constitutes “Appalachian music.” These include tourism bureaus, historical centers, music camps, music festivals—yes, even Appalachian Studies courses and textbooks. Every year, visitors to Appalachia drop in to the Ralph Stanley Museum in Clintwood, Virginia, take banjo classes at the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, North Carolina, and attend the Appalachian String Band Festival in Clifftop, West Virginia.47 None of these institutions presents an inaccurate version of “Appalachian music,” but each is incomplete, and each has been informed by the history outlined in this chapter. How might we reshape our notions of “Appalachian music” to include the musical activities of all Appalachians, past and present?

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Bibliography

Allen, Ray. “In Pursuit of Authenticity: The New Lost City Ramblers and the Postwar Folk Music Revival.” Journal of the Society for American Music 4 (2010): 277-305.

Brady, Erika. “Contested Origins: Arnold Shultz and the Music of Western Kentucky.” In Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music. Edited by Diane Pecknold, 100-18. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

Campbell, Gavin James. Music and the Making of a New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Campbell, Olive Dame, and Cecil Sharp. English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1917.

Cantwell, Robert. Bluegrass Breakdown: The Making of the Old Southern Sound. Urbana: University of Illinois, 1984.

Chaney, Ryan. “Straightening the Crooked Road.” Ethnography 14 (2013): 387-411.

Cohen, Norman. “The Skillet Lickers: A Study of a Hillbilly String Band and Its Repertoire.” Journal of American Folklore 78 (1965): 229-44.

Conway, Cecilia. African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A Study of Folk Traditions. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1995.

Davenport, Doris. “A Candle for Queen Ida.” Black Music Research Journal 23 (2003): 91-102.

Enriquez, Sophia M. “‘Penned Against the Wall’: Migration Narratives, Cultural Resonances, and Latinx Experiences in Appalachian Music.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32 (2020): 63-76.

Filene, Benjamin. Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Frost, William Goodell. “Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains.” Atlantic Monthly, March 1899. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1899/03/our-contemporary-ancestors-southern-mountains/581332/

Harkins, Anthony. Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Hay, Fred J. “Music Box Meets the Toccoa Band: The Godfather of Soul in Appalachia.” Black Music Research Journal 23 (2003): 103-33.

Horton, Laurel Mckay. “Lunsford, Bascom Lamar.” NCPedia. 1991. https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/lunsford-bascom-lamar

Huber, Patrick. “Black Hillbillies: African American Musicians on Old-Time Records, 1924-1932.” In Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music. Edited by Diane Pecknold, 19-81. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Jones, Brian. “Finding the Avant-Garde in the Old-Time: John Cohen in the American Folk Revival.” American Music 28 (2010): 402-35.

Jones, Loyal. Minstrel of the Appalachians: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford. 1984. Reprint, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002.

Keith, Jeffrey A. “Fiddling with Race Relations in Rural Kentucky: The Life, Times, and Contested Identity of Fiddlin’ Bill Livers.” In Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music. Edited by Diane Pecknold, 119-39. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Library of Congress. “Alan Lomax (1915-2002).” Biography, n.d. https://www.loc.gov/item/n50039476/alan-lomax-1915-2002/

Lightfoot, William. “A Regional Musical Style: The Legacy of Arnold Shultz.” In Sense of Place: American Regional Cultures. Edited by Barbara Allen and Thomas J. Schelereth, 120-37. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992.

Lightfoot, William. “The Three Doc(k)s: White Blues in Appalachia.” Black Music Research Journal 23, (2003): 167-93.

Mack, Kimberly. “She’s a Country Girl All Right: Rhiannon Giddens’s Powerful Reclamation of Country Culture.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32 (2020): 144-61.

Miller, Karl Hagstrom. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Morgan-Ellis, Esther M., ed. Resonances: Engaging Music in Its Cultural Context. Dahlonega: University of North Georgia Press, 2020.

Pearson, Barry Lee. “Appalachian Blues.” Black Music Research Journal 23 (2003): 23-51.

Romalis, Shelly. Pistol Packin’ Mama: Aunt Molly Jackson and the Politics of Folksong. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Stoddart, Jess. Challenge and Change in Appalachia: The Story of the Hindman Settlement School. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002.

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. “A Tribute to Pete Seeger.” n.d. https://folkways.si.edu/peteseeger

Whisnant, David E. All That is Native and Fine. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

Whisnant, David. “Finding the Way Between the Old and the New: The Mountain Dance and Folk Festival and Bascom Lamar Lunsford's Work as a Citizen.” Appalachian Journal 7 (1979): 135-54.

Winans, Robert B., ed. Banjo Roots and Branches. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Wright, Todd, and John Higby. “Appalachian Jazz: Some Preliminary Notes.” Black Music Research Journal 23 (2003): 53-65.

Wilson, Shannon. “William Goodell Frost: Race and Region.” Berea College, December 2017. https://libraryguides.berea.edu/frostessay

Zolten, Jerry. “Movin’ the Mountains: An Overview of Rhythm and Blues and Its Presence in Appalachia.” Black Music Research Journal 23 (2003): 67-89.

End Notes

- Harkins, Hillbilly, 30.

- Ibid, 34.

- Wilson, “William Goodell Frost.”

- Frost, “Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains.”

- Morgan-Ellis, Resonances, 144.

- Whisnant, All That is Native and Fine, 112.

- Ibid, 54.

- Filene, Romancing the Folk, 16.

- Stoddart, Challenge and Change in Appalachia, 87.

- Campbell and Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, iv.

- Ibid, ix-xi.

- Filene, Romancing the Folk, 27.

- Miller, Segregating Sound, 201.

- Campbell, Music and the Making of a New South, 128.

- Miller, Segregating Sound, 192.

- Cohen, “The Skillet Lickers,” 242.

- For a complete account of recorded Black string band musicians, see Huber, “Black Hillbillies.”

- Cantwell, Bluegrass Breakdown, 41.

- Lightfoot, “The Three Doc(k)s,” 186.

- Horton, “Lunsford, Bascom Lamar.”

- Whisnant, “Finding the Way Between the Old and the New,” 136.

- Ibid, 138-39.

- Jones, Minstrel of the Appalachians, 71-73.

- Whisnant, “Finding the Way Between the Old and the New,” 144.

- Williams, Staging Tradition, 23-26.

- Ibid, 20-21.

- Whisnant, All That is Native and Fine, 197-99.

- Ibid, 191-93.

- Ibid, 199-201.

- Morgan-Ellis, Resonances, 240.

- La Chapelle, I’d Fight the World, 55.

- Ibid, 30.

- Romalis, Pistol Packin’ Mama, 89, 130.

- Morgan-Ellis, Resonances, 369-72.

- Library of Congress, “Alan Lomax Biography.”

- Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, “A Tribute to Pete Seeger.”

- Jones, “Finding the Avant-Garde in the Old-Time,” 409.

- Allen, “In Pursuit of Authenticity,” 292.

- Ibid, 295.

- Lightfoot, “The Three Doc(k)s,” 186-87.

- Morgan-Ellis, Resonances, 455.

- In 2003, an entire issue of the Black Music Research Journal was dedicated to “Affrilachian Music,” or the music of Black Appalachians. Individual articles in the issue sought to undertake or make way for serious research on Affrilachian musical practices. See, for example, Pearson, “Appalachian Blues”; Wright and Higby, “Appalachian Jazz”; Zolten, “Movin’ the Mountains”; Davenport, “A Candle for Queen Ida”; and Hay, “Music Box Meets the Toccoa Band.”

- Lightfoot, “A Regional Musical Style”; Brady, “Contested Origins”; Keith, “Fiddling with Race Relations in Rural Kentucky.”

- Conway, African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia; Winans, Banjo Roots and Branches.

- Mack, “She’s a Country Girl Alright,” 145.

- Enriquez, “‘Penned Against the Wall.’”

- Chaney, “Straightening the Crooked Road,” 388.