Contents

- Overview

- Roots in West Africa

- Early Gourd Banjo in the Americas

- The Banjo and Blackface Minstrelsy

- The Elevation of the Banjo

- Ragtime and Jazz Banjo

- Rural Banjo

- Old-Time Banjo Recordings

- Bluegrass Banjo

- The Banjo and the Folk Music Revival

- The Banjo and Americana

- The Banjo Today

- Playlists

- Further Reading

Overview

The banjo is a stringed instrument that is, or has been, prominent in American folk, country, bluegrass, ragtime, and jazz music. Sharing design elements with many similar West African instruments, the banjo developed in the Caribbean during the first century of the transatlantic slave trade. It was played exclusively by Africans in America and African Americans during colonial times and the early United States. Starting in the 1840s, blackface minstrel performers began popularizing the banjo among middle-class Whites who purchased manufactured instruments and learned to play. By the end of the century, banjo repertoire had expanded from plantation and minstrel tunes to include sentimental popular songs, waltzes, mazurkas, polkas, and ragtime.

Played in the rural South since the second half of the nineteenth century, the banjo rose to become prominent in folk, country, old-time, and bluegrass music. Association with these genres, and the diminished presence of the instrument in twentieth-century African American music, led to the banjo becoming a representation of rural White culture. However, a wealth of historical research conducted since the 1970s has brought attention to the African roots of the banjo, and performers and scholars have been making efforts to restore the instrument’s place in Black culture.

Roots in West Africa

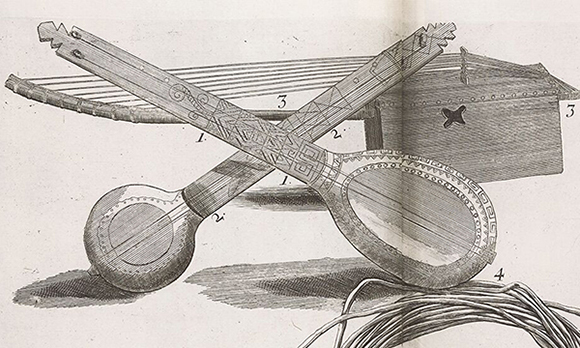

There is likely no single ancestor of the banjo. The instrument shares design elements and playing techniques with a family of approximately eighty known West African plucked spike lutes. Lutes are stringed instruments with necks that are distinct from their bodies. “Spike” implies that the neck passes over or through the body of the instrument. “Plucked” means that it produces sound when the strings are struck or plucked.

West African plucked spike lutes share three basic design features. The body is a hollow gourd, calabash, or carved wood, covered like a drum with an animal hide. A plain round stick serves as a neck. The strings are attached to the neck with leather or cloth rings. Players tune the instrument by sliding the rings up or down to tighten or loosen the strings.

The akonting, n’goni, molo, and gurmi are among the African relatives of the banjo. Musicians play these instruments with a down-stroke technique similar to the earliest known banjo playing in North America. The lead finger, usually the index or middle, strikes a string or strings with a downward motion, and the thumb sometimes plucks a string as the hand returns to starting position.

Ekona Diatta plays "Gambia" on the akonting (2007)

Early Gourd Banjo in the Americas

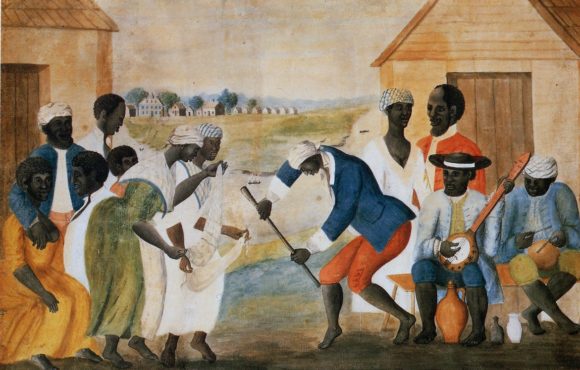

Enslaved West Africans in the Caribbean created a new instrument by incorporating elements of European instruments into the familiar design of their plucked spike lutes. Historians refer to these new instruments as early gourd banjos. They share features that differentiate them from West African lutes, including a flat, fretless fingerboard, wooden friction tuning pegs, and the way the neck enters and attaches to the gourd body. This design was firmly ingrained in the New World, as evidenced by the following instruments found across time and distance: the strum strump observed in Jamaica in the late 1680s, the early gourd banjo in John Rose’s watercolor (sometimes called The Old Plantation) from South Carolina around 1785, and the banza collected in Haiti in 1841.

Many details of these early gourd banjos are evident in the instruments built by European American banjo makers in the mid-nineteenth century. In the book Banjo Roots and Branches, historian Pete Ross concludes, “All three banjos differ enough from African instruments while sharing some details specific to later banjos played and made by European Americans to place them at a point in the banjo’s history where it was no longer simply a relocated African instrument, but on its way to attaining the structure of the well-known antebellum nineteenth-century banjo.”

There are more than eighty-five documented banjo sightings in North America between 1736 and 1840. All but four of these referenced Black musicians. Unlike the fiddle, which African Americans played far more commonly, the banjo was primarily a southern instrument. More than half of the banjos and players reported were in the Chesapeake Bay states of Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. The rest were widely scattered, with small clumps around New York City and New Orleans.

Black musicians played the banjo to accompany singing and dancing, sometimes with percussion or hand clapping. The instrument may also have been part of a religious ceremony known as the banya prei. The Old Plantation and Gerrit Schouten’s Slavendans dioramas from Suriname both appear to depict this ritual. In some historical records, "playing banya" or "playing banjo" may have referred to the dance ritual, not the musical instrument.

Matthew Sabatella plays "Pompey Ran Away" on a banjo built by Pete Ross. The banjo is patterned after detail from "The Old Plantation" painting.

The Banjo and Blackface Minstrelsy

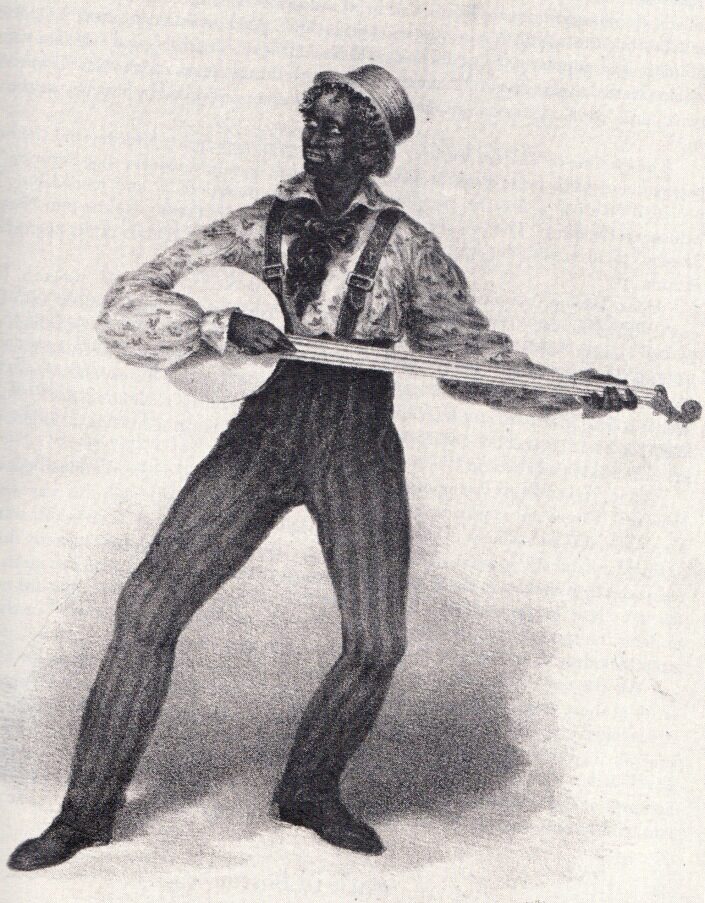

The banjo became prominent in the United States with the rise of blackface minstrelsy in the 1830s. For several decades, minstrel shows were the most popular form of entertainment in the United States. The practice continued in various forms, including film, radio, and television, into the 1950s. Minstrel shows featured music and comedy skits performed primarily by White men made up with burnt cork. Blackface characters portrayed African Americans in derogatory, clownish exaggerations. Minstrel troupes marketed themselves as an authentic representation of Southern plantation life. In reality, they were far from that, but they did incorporate elements from both Black and White folk culture.

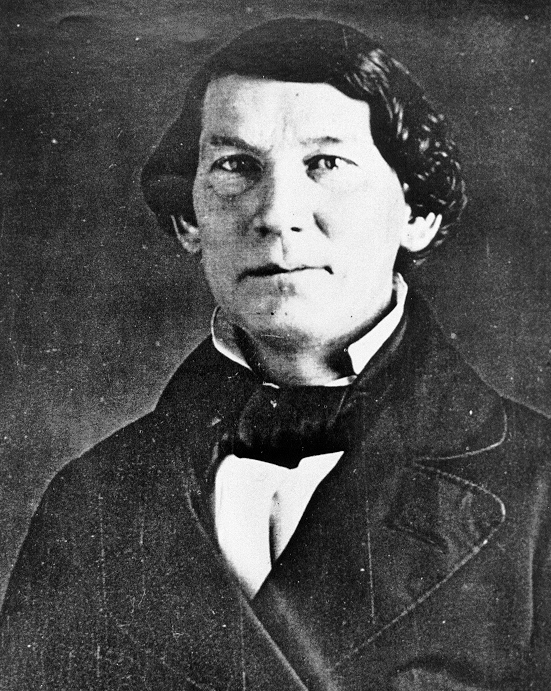

Thomas Dartmouth Rice started the minstrel craze in 1828 with his song and dance “Jump Jim Crow.” Joel Walker Sweeney was the first minstrel performer to play the banjo. He learned the instrument from Black musicians in his home state of Virginia. From 1836 on, Sweeney toured the United States and Europe in blackface, becoming the first superstar of the banjo. By the end of the decade, other White solo banjo players in blackface became popular on the circus and variety show circuit.

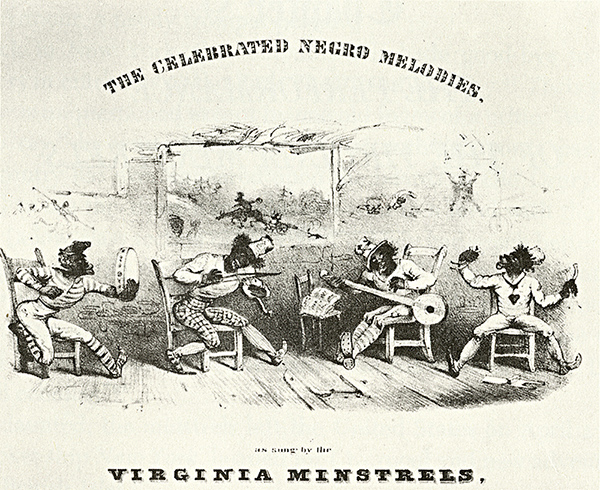

In 1843, a troupe called Virginia Minstrels put on the first full-length minstrel show in a New York City theater. The ensemble included banjo, fiddle, tambourine, and bones, a percussion instrument made from animal rib or shin bones. Virginia Minstrels spawned many imitators, and the instrumentation and general format of the skits and music became somewhat standardized.

The overwhelming popularity of minstrel shows created a demand for banjos from performers and people who wanted to learn to play the instrument at home. Until the 1840s, banjos were homemade gourd-bodied instruments. William Boucher, Jr., the earliest known commercial manufacturer, started building banjos around 1845 from his shop in Baltimore, Maryland. Boucher replaced the gourd with a wood-frame body, which could be mass-produced with much greater consistency. He used European drum technology to attach the head, which provided a mechanism for controlling the instrument’s tone.

Other banjo manufacturers emerged in the 1840s and the following decades. The Dobson brothers, William A. Cole, H.C. Fairbanks, James Ashborn, and Vega built banjos or affixed their names to the banjos of others.

The Elevation of the Banjo

By the 1850s, the banjo had become an integral part of American culture. Throughout the remainder of the century, banjo makers and music book publishers sought to increase sales among the burgeoning White middle class. Their attempts to elevate the instrument disassociated it from its African roots. In the process, banjos underwent significant changes in structure, appearance, and repertoire.

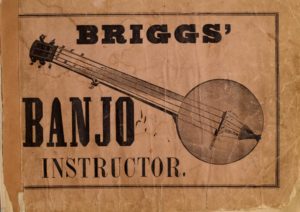

In 1855, Tom Briggs, a minstrel banjo player and teacher, published Briggs’ Banjo Instructor, the first in a series of banjo tutors published over the following decades. These books demonstrate a transition in playing technique from the African-rooted downstroke, utilized by Black musicians and minstrel performers, to an up-picking method common among guitarists. This technique has come to be known as guitar, or classic, style. The musical repertoire in the tutors expanded to include sentimental popular songs, European waltzes, mazurkas, and polkas. While Briggs' tutor includes guitar-style playing in addition to downstroke, he was more interested in promoting his invention, the banjo thimble. The banjo thimble, a precursor to the fingerpicks that are standard in bluegrass playing, increased the volume of banjo soloists performing in the downstroke style on stage.

Timothy Twiss plays the basic movements described in Briggs' Banjo Instructor

Also during the second half of the nineteenth century, banjo manufacturers began installing frets on the instrument. Frets are metal strips inserted into the fingerboard of string instruments that divide the neck into fixed intervals. Fretted instruments, such as guitars and mandolins, are generally easier to play in tune than unfretted instruments, such as violins, violas, and cellos. However, the nature of the fixed intervals requires some compromise in intonation. Most banjos today are fretted, though some musicians play fretless.

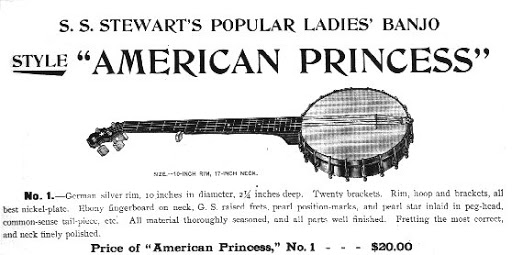

To make the banjo more appealing to middle-class Americans, manufacturers put more attention on physical aesthetics. They made smaller instruments and added intricate pearl inlays to the neck and headstock. Companies designed banjos particularly for young ladies and targeted marketing campaigns at these principal purveyors of music in Victorian-era parlors.

To make the banjo more appealing to middle-class Americans, manufacturers put more attention on physical aesthetics. They made smaller instruments and added intricate pearl inlays to the neck and headstock. Companies designed banjos particularly for young ladies and targeted marketing campaigns at these principal purveyors of music in Victorian-era parlors.

Starting in the 1880s, amateur musicians formed banjo, mandolin, and guitar (BMG) clubs. These groups were common, especially on college campuses. Members of BMG clubs played plucked stringed instruments in a variety of sizes and shapes.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the banjo had become the most popular fretted, stringed instrument in America.

Ragtime and Jazz Banjo

The 1890s brought the dawn of recorded sound with Thomas Edison’s phonograph and Emile Berliner’s gramophone. The banjo featured prominently in records manufactured and sold in the first decades of the industry. Sylvester Louis “Vess” Ossman was one of the most popular recording artists of his time. Between 1893 and 1917, he made more than 500 recordings of ragtime songs, marches, and minstrel material.

Vess Ossman: "The Buffalo Rag" (1906)

In the early twentieth century, manufacturers introduced the four-string, or tenor, banjo. It was tuned in fifths, like a mandolin or violin, and played by strumming with a plectrum, also known as a pick. The tenor banjo lacked the short fifth string, which provided a single-note musical drone. When ragtime and blues music melded into jazz in the 1910s, the tenor banjo was one of the principal instruments in the rhythm section. Its loud, bright sound cut through jazz bands and dance orchestras, providing a solid rhythm.

Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five with Johnny St. Cyr on banjo: "Gut Bucket Blues" (1926)

Through the 1920s and early 1930s, the guitar gradually replaced the banjo in jazz ensembles. Physical improvements in the instrument had enabled it to produce a sufficiently loud sound. By the early 1940s, musicians introduced electric guitars in jazz and blues. As African American musicians continued their innovations in blues, rhythm and blues, and gospel music, the guitar’s sustain and deep bottom end suited their musical needs better than the banjo. While some continued to play the instrument, there was a steep decline in the presence of the banjo in Black music.

Rural Banjo

As the banjo made inroads into middle-class American parlors during the second half of the nineteenth century, it also became integral to the music of the rural South. Many White musicians learned to play banjo directly from African Americans. Though there is little documentation, some may have picked up the instrument before the rise of minstrelsy. The two races lived in close proximity in the Appalachian Mountains, Piedmont, and other parts of the South, interacting socially and playing music together for dances.

The pairing of fiddle and banjo, which integrated Celtic American fiddle and African American banjo styles, became central to song and dance traditions. The instruments were at the core of White, Black, and integrated string bands, which might also include guitar, mandolin, harmonica, or other instruments. String bands primarily provided music for square dances and step dances in southern Appalachia.

Tommy Jarrell and string band with Ray Chatfield on banjo: "Sally Anne" (1983)

Musicians adapted various genres to the banjo, including fiddle tunes, popular sentimental songs, ballads from the British Isles, and songs from the minstrel stage. They also composed new songs on the banjo, often devising unique tunings for the instrument to achieve the desired tonalities. They played in both the African-rooted downstroke style, now commonly called frailing or clawhammer, and the two- and three-finger up-picking guitar styles taught in the banjo tutors.

B.F. Shelton: "Darlin' Cora" (1927)

Some localities in the Appalachians developed distinctive designs for homemade banjos. As products from mail-order companies like Sears & Roebuck became available in the late nineteenth century, rural Americans increasingly purchased inexpensive manufactured instruments.

Old-Time Banjo Recordings

In the 1920s, record companies discovered and nurtured a market for Southern rural music. They recorded string bands and solo musicians, often on location in makeshift recording studios, and released the music under the labels “old-time,” old familiar tunes,” or “hillbilly.” Samantha Bumgarner from Dillsboro, North Carolina, recorded ten songs for Columbia Records in April 1924. She may have been the first Appalachian banjo player to cut a commercial record.

Samantha Bumgarner (banjo) and Eva Davis (fddle): "Cindy in the Meadow" (1924)

Uncle Dave Macon was a skilled musician and showman who gained regional fame as a vaudeville performer in the early 1920s. He became the first star of the Grand Ole Opry radio broadcast. Macon incorporated multiple techniques, including clawhammer and two- and three-finger up-picking, into his banjo playing.

Uncle Dave Macon: "Take Me Back to My Old Carolina Home"

Clarence “Tom” Ashley, Dock Boggs, Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Buell Kazee, and other rural banjoists recorded in the 1920s using various techniques. Charlie Poole, who started playing a gourd banjo in his childhood, recorded many sides for Columbia Records in the late 1920s. His three-finger guitar style had a significant influence on the bluegrass players of the 1940s.

Charlie Poole with the North Carolina Ramblers: "Don't Let Your Deal Go Down Blues" (1927)

Black string bands still performed at community dances at this time. Because they did not fit the White stereotype of hillbilly music, record companies were not interested in recording them, though occasionally Black musicians played in the background on records by White artists.

Murph Gribble (banjo), Albert York (guitar), and John Lusk (fiddle): "Altamont" (1946)

Gus Cannon was a versatile and influential African American banjo player. During the late 1920s, he recorded for various companies’ race record lines, which captured African American blues, jazz, and gospel music and marketed to Black record buyers. Cannon’s output included bluesy and jazzy music, and he played banjo with both downstroke and up-picking styles.

Cannon's Jug Stompers: "Walk Right In" (1929)

Bluegrass Banjo

In the late 1930s, mandolinist, singer, songwriter Bill Monroe formed The Blue Grass Boys, the band primarily responsible for developing bluegrass music. Bluegrass is rooted in the rural music of Appalachia as captured on the old-time string band recordings of the 1920s and 30s. However, bluegrass incorporates jazz influences and emphasizes instrumental virtuosity and improvised solo breaks, which were not prevalent in old-time music.

When Earl Scruggs replaced original Blue Grass Boys banjo player David “Stringbean” Akeman in 1945, the bluegrass sound fully emerged. Akeman played in the older clawhammer style and rarely took an improvised solo. Scruggs was a 3-finger up-picking virtuoso who soloed frequently and took the banjo to inventive new places. His eighth-note arpeggio patterns, called “rolls,” have been widely imitated. To this day, players who emulate his techniques are said to be playing either bluegrass- or Scruggs-style banjo.

Earl Scruggs and His Blue Grass Boys with Earl Scruggs on banjo: "Why Did You Wander"

Scruggs and guitarist Lester Flatt left the Blue Grass Boys to form Flatt & Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys in 1948. They were instrumental in bringing bluegrass to a wider audience through television, radio, and live performances. The sound of the banjo became commonplace with their theme song for the television show The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971) and the prominent placement of their instrumental “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” in the 1967 film Bonnie & Clyde.

Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs: "Foggy Mountain Breakdown" (1949)

Other prominent bluegrass banjo players, including Don Reno, Sonny Osborne, and Bill Keith, followed in Scruggs’ footsteps and broke ground of their own. While musical tradition runs strong in bluegrass, a generation of younger players started taking the music in new directions in the 1970s. Progressive bluegrass, or newgrass, draws from a wider pool of musical influences than traditional bluegrass and might include more rock and jazz elements. Pioneers of progressive bluegrass include John Hartford, New Grass Revival, featuring banjo virtuoso Bela Fleck, and J.D. Crowe’s New South, featuring Crowe on banjo. Progressive bluegrass continues today with artists such as Alison Krauss and Union Station, Infamous Stringdusters, and Yonder Mountain String Band.

J.D. Crowe & The New South: "Old Home Place" (1975)

The Banjo and the Folk Music Revival

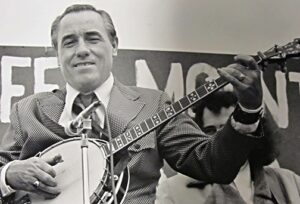

Between the 1930s and 1960s, American roots music enjoyed successive waves of interest. Pete Seeger, son of musicologist Charles Seeger, first heard the 5-string banjo in 1936 at the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in western North Carolina, organized by Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Intrigued by what he witnessed and the banjo, in particular, the younger Seeger began learning to play. The banjo became his instrument of choice in work as an activist and advocate for folk music and group singing. With the group The Weavers, formed in 1948, Seeger took the banjo to the top of the popular music charts multiple times, though the orchestra arrangements on many of their recordings obscured it.

The Weavers with Pete Seeger on banjo: "On Top of Old Smoky" (1951)

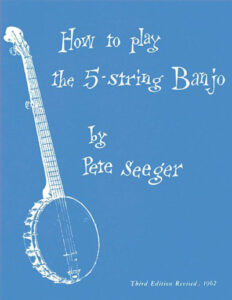

Seeger’s 1948 book How to Play the 5-String Banjo taught countless aspiring banjo players.

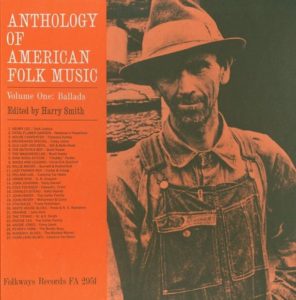

In 1952, Folkways Records released Anthology of American Folk Music, which prompted tremendous interest in the raw, rural sounds of the banjo. The Anthology was a set of six long-playing records that compiled eighty-four songs initially released on old-time and race record lines in the 1920s and 30s. The collection became popular with urban college students and inspired many young musicians, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Jerry Garcia.

Realizing the recordings were made only a few decades earlier, disciples of the Anthology began seeking out some of the performers. Old-time banjo players Clarence Ashley and Dock Boggs enjoyed new opportunities to record and perform on stage at folk festivals, coffeehouses, and college campuses.

Dock Boggs: "Country Blues" (1966)

In 1958, Mike Seeger (Pete’s half-brother), Tom Paley, and John Cohen formed the New Lost City Ramblers, a young group that remained faithful to old-time music traditions. They learned directly from the older masters and recorded them to capture their stories, wisdom, and musical approach.

New Lost City Ramblers: "I Truly Understand" (1958)

Other musicians polished up the old sounds and made slick new commercial recordings. The Kingston Trio, with banjo player Dave Guard, released their first album in 1958. The album included their interpretation of “Tom Dooley,” a song that was already old when G.B. Grayson and Henry Whitter first recorded it in 1929. The Kingston Trio’s version sold more than three million copies as a single.

The Kingston Trio: "Tom Dooley" (1958)

The Banjo and Americana

The folk music revival took a turn towards folk-rock in the mid-1960s, as Bob Dylan plugged in, and the Byrds played folk songs with electric guitars. In 1968, the Byrds brought it back home with their album Sweetheart of the Rodeo, hailed by many as among the first country-rock albums. Roger McGuinn, whose electric 12-string guitar sound defined the Byrds’ earlier music, played banjo on some songs, as did virtuoso John Hartford.

The Byrds with John Hartford on banjo: "I Am a Pilgrim" (1968)

Poco, New Riders of the Purple Sage, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and others carried country-rock into the 1970s and beyond. The genre is part of the Americana or American roots music category, which includes elements of traditional folk, country, blues, rhythm and blues, and gospel music. Emmylou Harris, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Neil Young, the Eagles, Pure Prairie League, Linda Ronstadt, and Gillian Welch have created music within these spaces, often featuring banjo in their recordings.

Gillian Welch: "Hard Times" (2011)

The Banjo Today

Today, the banjo can be heard in virtually every genre of music. Bluegrass, both progressive and traditional, old-time, and Americana music are still going strong in recordings, concerts, and gatherings of musicians and fans at festivals. Folk rock bands, including Mumford & Sons and the Avett Brothers, have introduced the instrument to younger mainstream audiences. Virtuosos like Bela Fleck have continued to extend the range of what a banjo can do.

Bela Fleck, Edgar Meyer, Zakir Hussain: NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert (2010)

The disassociation of the banjo from its African roots is starting to reverse. Beginning in 1977 with Dena Epstein’s book Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War, scholars have published extensively on the early history of the banjo. New generations of Black musicians have taken up the instrument and are making efforts to preserve its place in African American culture. Prominent players today include Jake Blount, Otis Taylor, Corey Harris, and Taj Mahal. In 2005, the Carolina Chocolate Drops brought together four African American musicians playing traditional string band music on fiddle, banjo, guitar, and various other instruments. Their 2010 album Genuine Negro Jig won a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album.

The Carolina Chocolate Drops with Dom Flemons on banjo: "Country Girl" (2012)

Rhiannon Giddens and Dom Flemons, former members of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, continue to perform, explore, and tell the banjo’s story in live performances, recordings, writings, and interviews. In 2019, Giddens, in collaboration with Black banjo players Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, and Allison Russell, released the album Songs of Our Native Daughters. “Much of what is deemed folk music has its roots in Africa and African American tradition,” notes Giddens. “I am obsessed with banjo as a tool of reclamation for African American artists.”

Our Native Daughters with Allison Russell on banjo: "Quasheba, Quasheba" (2020)

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Further Reading

Chuck Levy, Shlomo Pestcoe, Pete Ross, Tony Thomas, and Saskia Willaert. Banjo Roots and Branches. Edited by Robert B. Winans. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Carlin, Bob. Banjo: An Illustrated History. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 2016.

Carlin, Bob. The Birth of the Banjo: Joel Walker Sweeney and Early Minstrelsy. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2007.

Conway, Cecelia. African Banjo Echoes In Appalachia: Study Folk Traditions. University of Tennessee Press, 1995.

Dubois, Laurent. The Banjo: America’s African Instrument. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Gaddy, Kristina R. Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo's Hidden History. W.W. Norton & Company, 2022.

Gura, Philip F., and James F. Bollman. America’s Instrument: The Banjo in the Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Linn, Karen. That Half-Barbaric Twang: The Banjo in American Popular Culture. Urbana: Illini Books, 1994.

Mazow, Leo G. Picturing the Banjo. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2006.