It is almost impossible to overestimate the impact that Anthology of American Folk Music has had on music, both directly and indirectly. It inspired countless musicians and songwriters, including Bob Dylan, Elvis Costello, Jeff Tweedy, Jerry Garcia, John Sebastian, The Fugs, and their followers. Author Greil Marcus wrote that the Anthology was "the founding document of the American folk revival" of the 1950s and 1960s. According to musician Dave Van Ronk, a key figure in the revival, "(The) Anthology was our bible… We all knew every word of every song on it, including the ones we hated." The set brought virtually unknown parts of America's musical landscape to people's attention, introducing generations of Americans to the music of their heritage.

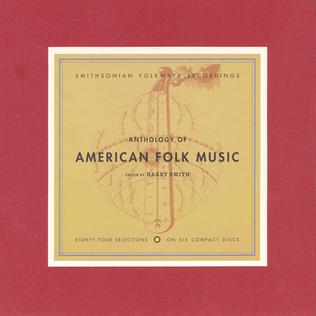

The Anthology was originally released by Folkways Records in 1952 on six long-playing records. The set contains eighty-four recordings that were made and issued on 78 rpm records between 1927 and 1932. The music included Appalachian ballads, fiddle tunes, country blues, Cajun, jug band, sacred harp, and more. It is organized in three volumes, with two discs dedicated to each: Ballads, Social Music, and Songs. In 1997 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings released it on compact disc with expanded essays and annotations.

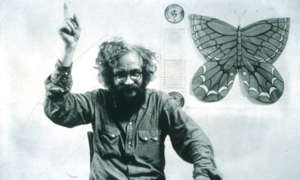

The songs were chosen, sequenced, and annotated by West Coast visual artist, experimental filmmaker, record collector, and mystic, Harry Smith. Smith indicated that his hope in assembling and releasing the Anthology was to see "America changed by music." The success of the Anthology led to the reissue of many other early recordings and is largely responsible for the general interest in roots music that continues to this day. Considering this ongoing impact, it’s hard to deny that Smith succeeded in changing America.

Volume One: Ballads

Ballads features narrative, or storytelling songs. It begins with a set of ballads transplanted from the British Isles and continues with indigenous ballads that were born in the United States.

British Ballads

The ballad tradition as we know it today is traceable to the minstrels and troubadours who traveled and entertained throughout most of Europe during the Middle Ages. A repertoire of common ballads evolved in the British Isles from the 15th through the 18th century. The old British ballads tell stories of nobility, romance, love, family strife, heroes, monsters, ghosts, death, betrayal, and murder. Many of these ballads were carried in the hearts and minds of immigrants to Colonial America. They were commonly sung in America and passed down to subsequent generations orally.

Ballads opens with a series of five Old World ballads that can be found in Francis James Child's seminal work The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. The books, published in five volumes between 1882 and 1898, catalog the texts of 305 distinct ballads and 1,660 variants. Originally sung unaccompanied, by the 1920s and 1930s when the recordings on the Anthology were made, they were often sung with instrumental accompaniment that might include guitar, banjo, fiddle, dulcimer, or any combination of these and other instruments in a small string band.

"The House Carpenter," was recorded in 1930 by singer and clawhammer banjo player Clarence Ashley. All versions listed by Child are of Scottish origin, though details of the story differ. Ashley is from Shouns in East Tennessee and sang with medicine shows in the 1920s and 1930s. He is one of several Anthology artists who had a second career performing and recording music in the 1960s after being rediscovered by young folk revivalists, who had initially assumed all the artists from the Anthology had long since passed.

Heavily influenced by the music of the Anthology, Bob Dylan recorded "The House Carpenter" during the November 1961 recording sessions that produced his eponymous debut album. This recording was not included on the album, which consisted almost entirely of traditional folk songs. His recording of "The House Carpenter" was eventually released as part of The Bootleg Series Volumes 1 - 3, issued in 1991.

Indigenous Ballads

Following the five Child ballads, the Anthology moves into indigenous ballads that were born in the United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries. They generally recount actual events and were composed soon after the events occurred. Indigenous ballads, like British ballads, are often of unknown origin and developed many variants through the singing of people who transmitted them orally over the years. They tell stories of crime, love, natural disasters, and change brought about by the industrial revolution.

"Kassie Jones" recounts events related to an actual train wreck that occurred on April 30, 1900, killing engineer John Luther Jones. Jones was from the town of Cayce, Kentucky, which is how he attained his nickname, usually spelled "Casey." The song was written by Wallace Saunders, a close friend of Jones, a few days after the wreck. It might more accurately be identified as a blues ballad, because it does not strictly follow the events of the story, as ballads generally do. The version of "Kassie Jones" on the Anthology was recorded by Memphis bluesman Walter "Furry" Lewis on August 28, 1928. Like Ashley, Lewis had a second career in music later in life after being rediscovered during the folk music revival by disciples of the Anthology.

Volume Two: Social Music

Social Music focuses on music as a part of community events, specifically dance and worship. The first fourteen tracks include various forms of dance music, and the remaining fifteen songs are church and religious music.

Dance Music

Dancing was the most common pastime in colonial America and the early United States. The wealthier classes danced couples dances, primarily from France, including minuets, gavottes, and bourrees. People of all classes enjoyed country dances. New American dance traditions, including the square dance, emerged from Scots-Irish reels, English, French, African, and Native American dance elements.

The first track on Anthology of American Folk Music Volume Two - Social Music is a 1926 unaccompanied violin recording of "Sail Away Lady" by "Uncle Bunt" Stephens. Smith notes that the style of this performance is probably typical of American dance music between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Early European settlers generally used unaccompanied violin for dancing.

The African-derived banjo became a common accompaniment to the violin during the mid-19th century. The Spanish-derived guitar came into the mix in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. String bands consisting of fiddle, guitar, banjo, and sometimes mandolin and double bass, were popular in the 1920s and 1930s, laying the foundation for bluegrass and country music. "Brilliancy Medley," recorded by Eck Robertson and Family in 1930, features violin with banjo and two guitars. Smith notes that this "medley of traditional tunes is more suited to the popular dance steps of the 1920s than for the square dance."

Social Music also includes a few Acadian dance tunes, a jug band song, and a jazzy song that is "one of the musical ancestors of Spike Jones."

Religious Music

Early Protestants in the New World sang a type of religious song called a psalm. Psalms were sung at a slow tempo without instrumental accompaniment. A new, livelier form of religious song called a hymn came with the Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s. Hymns were especially popular with African Americans as they converted to Christianity. When the Second Great Awakening swept through the United States from the 1780s through the 1850s, African Americans created a new form of religious song called a spiritual, which was informed by the earlier hymns but included uniquely African and African American elements. African American and European American religious musics influenced each other through the 20th century.

The set of religious songs on Social Music begins with two "lining hymns" from Rev. J.M. Gates. In a lining hymn, the leader chants a phrase which is then sung by the congregation or choir. Smith identifies this style of song as "one of the earliest modes of Christian religious singing in this country."

Two shape note songs from The Sacred Harp song book, first published in 1844, follow the lining hymns. Shape note singing originated in New England and was perpetuated in the American South. Shape note songbooks represent the notes of the melody with different shapes to identify the appropriate pitch. The method was devised so people who don't read standard musical notation can join the singing. In the first part of the song, instead of the lyrics, singers sing the name of the scale position - fa, sol, la, or mi.

Other unaccompanied vocal performances follow in addition to some with instrumental accompaniment. Blind Willie Johnson recorded "John the Revelator" in 1930. Johnson made some of the most popular African American religious song recordings of the time.

Social Music concludes with Rev. D.C. Rice and His Sanctified Congregation's notably contemporary, jazz-inflected performance of "I'm in the Battle Field for My Lord" from 1929.

Volume Three: Songs

All three volumes of the Anthology contain "songs" by most definitions of the word. Volume three features non-narrative folk songs, including blues, cowboy, jug band, and other forms that don't quite fit within the parameters of the other two volumes, Ballads and Social Music. Many are of the type that Smith categorizes as "folk-lyric." These are songs made up of verbal fragments or floating verses that have been shared among multiple songs and don't necessarily connect logically to each other within a song.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford recorded the song "I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground" in 1928 for the Brunswick record label. Lunsford was a country lawyer and musician from Madison County in western North Carolina. Known as "The Minstrel of the Appalachians," he traveled extensively through the mountains collecting folk songs. In his later years, he recorded 350 songs for the Library of Congress.

Novelist Robert Cantwell wrote the following about Lunsford's recording of "I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground."

Listen to "I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground" again and again. Learn to play the banjo and sing it yourself over and over again, study every printed version, give up your career and maybe your family, and you will not fathom it.

This writer can attest to that statement, having engaged in most of the aforementioned activities.

Lemon Henry "Blind Lemon" Jefferson was one of the first rural or country blues artists to achieve popular success with just guitar and voice. Born blind in Wortham, Texas, Jefferson earned money busking in the streets of Dallas. He also traveled extensively, sometimes in the company of singer/guitarists Josh White or Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter. He made a series of successful recordings for Paramount Records between 1926 and his death in 1929. The Anthology includes Jefferson's "See That My Grave is Kept Clean," recorded in 1928 at his last recording session before his death the following year.

The Memphis Jug Band, led by singer, songwriter, guitarist, and harmonica player Will Shade, recorded "K.C. Moan" in 1929. Jug bands flourished in the first decades of the 20th century, especially in cities along the Mississippi River. Their styles mixed jazz, blues, ragtime, and string band music. Jug bands played homemade instruments such as the jug, washtub bass, washboard, spoons, comb and tissue paper kazoo, in addition to manufactured instruments that might include guitar, banjo, harmonica, and mandolin.

Henry Thomas' 1929 recording of "Fishing Blues" closes the Anthology. Author Greil Marcus notes that there is an "almost absolute liberation" in the song. Thomas plays guitar and quills, a form of pan-pipe made from cane that has its origins in Africa. You may recognize the sound of the instrument from the Canned Heat hit "Goin' Up the Country."

The Anthology of American Folk Music is one of the most influential albums of the 20th century. Singer/songwriter Elvis Costello noted, "First hearing the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music is like discovering the secret script of so many familiar musical dramas. Many of these actually turn out to be cousins two or three times removed, some of whom were probably created in ignorance of these original riches." The "original riches" of the Anthology are still available to inspire all who choose to explore them.