Overview

“Swannanoa Tunnel,” also known as “Asheville Junction” and “Swannanoa Town,” is an American folk song that originated during the late 19th century as a work song. African American prison laborers leased to Western North Carolina Railroad sang it as they swung their hammers and blasted a series of tunnels to let trains pass through the Blue Ridge Mountains. An estimated 125 – 300 convicts died during the construction of these tunnels. White folklorists and banjo players adapted the song and kept it circulating through the 20th century, obscuring its African American origins.

Historical Background

The Swannanoa River flows down from the Swannanoa Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina. Archeological evidence indicates that humans have inhabited the Swannanoa Valley created by the river for more than 12,000 years. The Cherokee Nation hunted bears, turkeys, buffalo, bobcats, and other animals on these grounds. After the American Revolution, European Americans settled in the area. The Cherokee were forcibly removed with the Indian Removal Act of 1838.

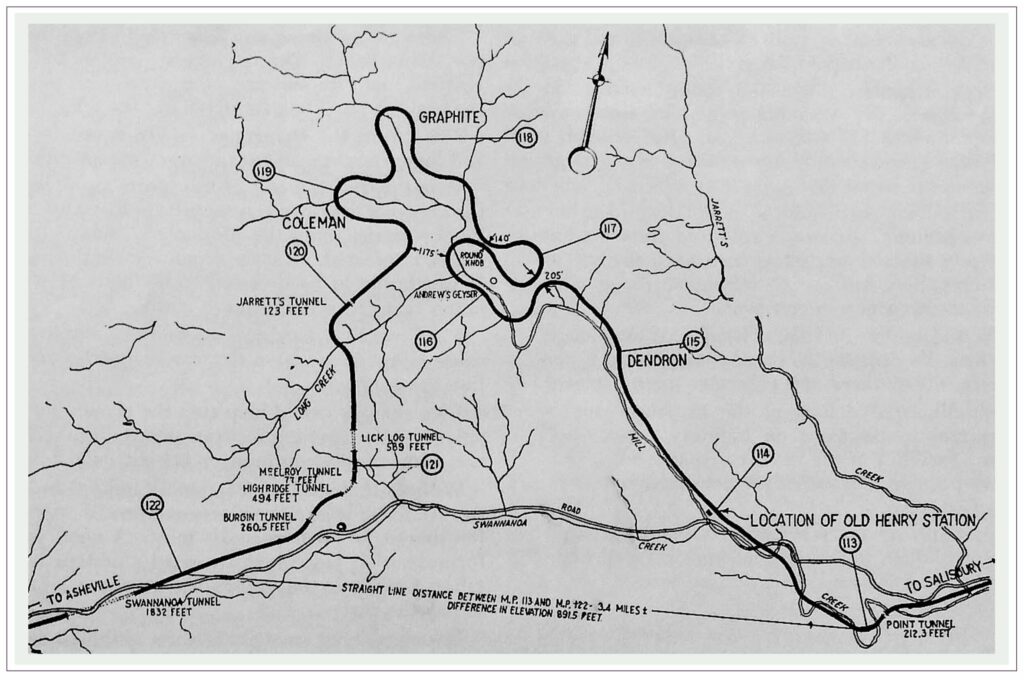

Western North Carolina Railroad (WNCR), incorporated in 1855, laid tracks to carry raw resources from the area, including timber from old-growth forests, to the East Coast ports and the global market. The Swannanoa Gap had provided the most convenient land route for settlers to cross the mountains on foot and by stagecoach, but it was too steep for a train to pass. Following the Civil War, WNCR set about tunneling through Swannanoa Mountain so trains could move goods between Western North Carolina and the Atlantic seaboard. Two crews working from opposite ends of the tunnel met on May 11, 1879. “Daylight entered Buncombe County today through the Swannanoa Tunnel,” wired James H. Wilson, chief engineer of WNCR, to North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance. The work had been done almost entirely by African American convict laborers.

As early as 1862, enslaved African Americans under contract between their owners and WNCR were sent from the eastern part of the state to lay railroad tracks. With the end of slavery as an institution, the state forced convicts to work in both the public and private sectors. Many were sold to work for railroads, lumber camps, coal mines, and plantations. The convict labor system provided a convenient alternative to slavery. The 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in December 1865, codified this system, stating “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

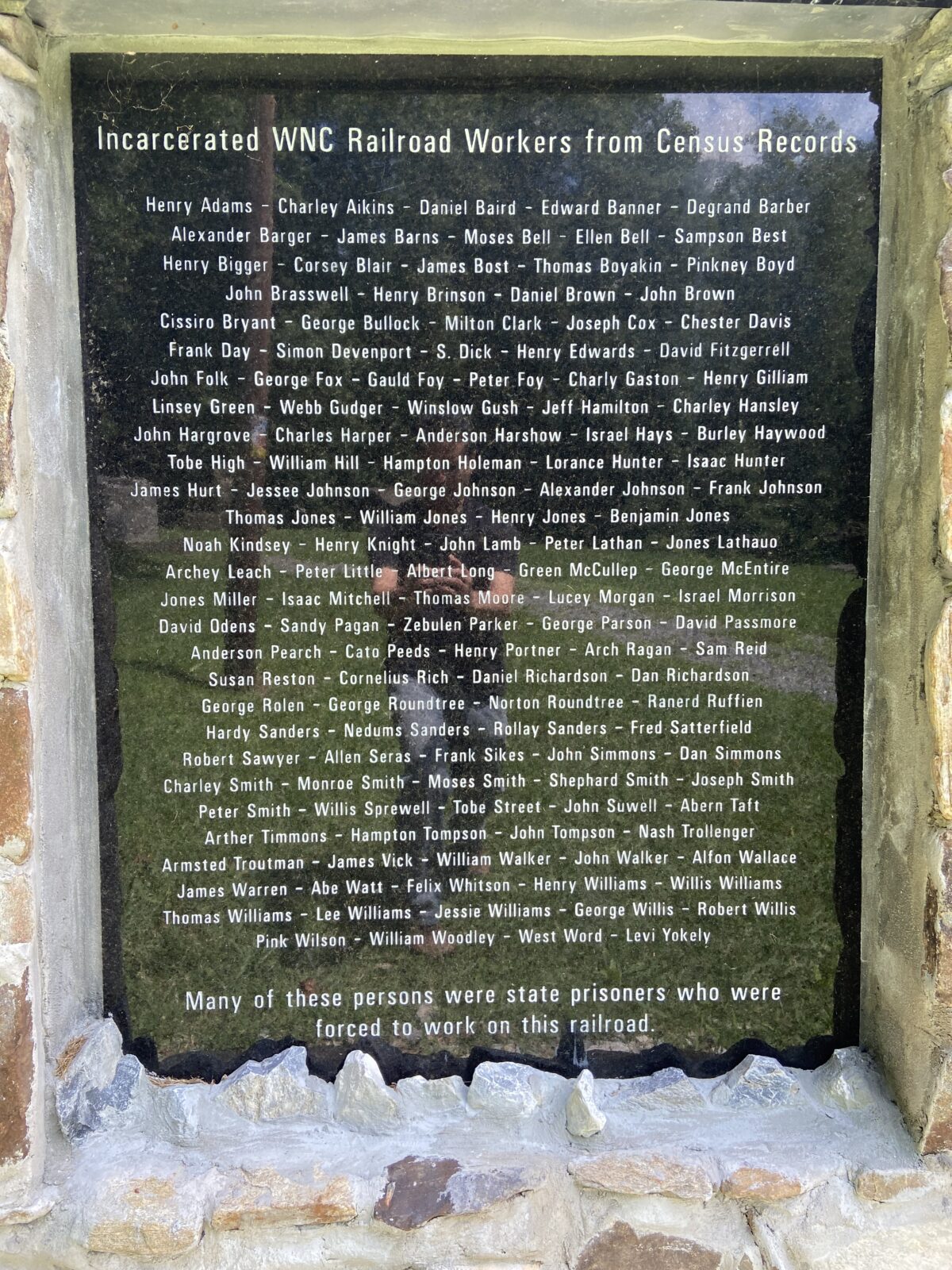

Throughout the South, tens of thousands of African Americans were arbitrarily arrested. New laws enabled states to imprison African Americans for crimes such as vagrancy, which meant not having a job. “Pig laws” dictated that a person could be imprisoned for five years for stealing a farm animal worth as little as one dollar. Nearly 90% of the convicts in North Carolina during these years were African American.

The tracks required to pass through the mountains at Swannanoa Gap wound around in about eight circles to make the ascension. Six tunnels also needed to be cut. The Swannanoa Tunnel was the most challenging and longest, covering a distance of 1,832 feet.

In late 1876, the first group of approximately 300 convicts was shipped to Henry Station, three miles west of Old Fort, the western terminus of the WNCR. By the time the tunnel was completed in 1879, some 3,000 inmates had been forced to work from sunup to sundown on the project. When not working, they were bound by chains in filthy railroad cars.

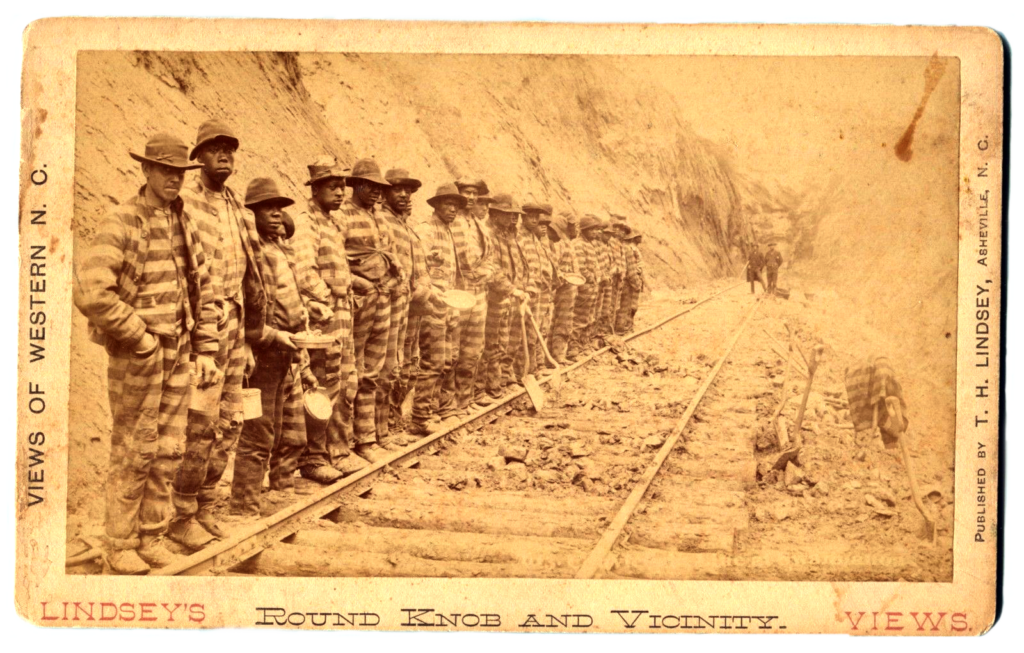

The tunneling work was difficult and dangerous. Teams of two or three men drilled holes in the rock. A shaker held a steel drill bit against the rock while a hammer man landed blows on it. The shaker shook the rock and dust loose, and the hammer man struck again. Sometimes two hammer men alternated strikes. When the hole was deep enough, they tamped into it a mix of sawdust, cornmeal, and nitroglycerin. After igniting the mixture, they carried away the blasted rock and drilled a hole for another explosion.

During the construction of the Swannanoa Tunnel, between 125 and 300 convicts died from cave-ins, explosion accidents, and disease. Others were shot by prison guards. They lie today in unmarked graves alongside the railroad track in and around the tunnel. The Railroad and Incarcerated Laborer Memorial (RAIL) Project works today to recognize and memorialize these workers.

Song History

When the hammer crews were working, they often sang hammer songs, a subcategory of work songs. As the timing of the hammer man, or men, and shaker was critical for safety and efficiency, hammer songs provided a steady rhythm by which to work. Lyrics, often improvised, commented on working conditions, struggles, strength, and resistance. The steel-driving man John Henry is referenced in many hammer songs, including “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Henry, a convict laborer who worked himself to death, served as a hero and cautionary tale.

Will “Shorty” Love’s version of “Swannanoa Tunnel,” recorded as “Asheville Junction” for Duke University folklorist Frank C. Brown in 1939, perhaps most closely resembles the original hammer song. Love, an African American employee at Duke, sang unaccompanied while pounding a table to mimic hammer strikes.

Audio recording courtesy of Duke University archives

WNCR’s convict laborers were permitted time for rest and recreation on Saturday nights and Sundays. They often sang and played music on the fiddle, banjo, or guitar during these times. On occasion, visitors from the community came by to hear their songs. When these visitors heard “Swannanoa Tunnel,” some learned to sing and play it, and the song began to travel.

Folk song collector Cecil Sharp published a version of “Swannanoa Tunnel” in his 1917 book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. Sharp was an Englishman who believed that songs from English culture had been preserved in the Appalachian Mountains untainted by outside influences. He collected “Swannanoa Tunnel” from the singing of two White women who lived a few miles west of the tunnel. Perhaps misunderstanding the words they sang, he documented and published it as “Swannanoa Town, O” and claimed it as English in origin. This title and lyric persisted in later published and recorded versions.

Artus Moser was born in 1894 and grew up in Western North Carolina. He collected hundreds of folk songs in this region, which he contributed to the Library of Congress. In 1955, he recorded a version of “Swannanoa Tunnel” as “Swannanoa Town” for his Folkways album North Carolina Ballads. The liner notes for the album indicate that Black prison laborers sang the song and that “until recently, many people in the vicinity of Swannanoa knew this song.” He contests the notion that Sharp misheard “tunnel” as “town-o” and theorizes that “the people in the area, proud of the song and the things it helped to accomplish, adapted it to their own devices when it no longer served as a work song.”

Artus Moser "Swannanoa Town" (1955)

Bascom Lamar Lunsford, born in Mars Hill in 1882, is probably most responsible for the enduring popularity of “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Lunsford was a lawyer, folklorist, and performer whose mission was “spreading the gospel of folk music,” especially from his region. He collected and memorized hundreds of folk songs and ballads that he could perform at will – his so-called “memory collection.” Lunsford learned “Swannanoa Tunnel” from a White banjo player named Fletcher Rymer. It became one of his signature songs. He recorded it multiple times and established it as a representative song from the region.

Lunsford’s book 30 and 1 Folk Songs from the Southern Mountains lists “Swannanoa Tunnel” as “an old labor song” sung by “section hands” who built the tunnel, making no mention of African Americans or convict labor. One of the printed verses appears to shift the song’s perspective from that of a worker to that of a prison guard overseeing the laborers – “When you hear my pistol firin’, ‘nother n----- dead, baby, ‘nother n----- dead.” Lunsford sings this verse on his 1935 recording for the Department of English at Columbia University. Lunsford tells Columbia that the song “possibly was brought to that great section by the construction men, Negroes, who worked in the construction of the great Swannanoa Tunnel. Then it has been influenced a great deal by mountain sentiment. Often in that section, where music has been brought in, then the mountaineer works it over and uses it to his own taste.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s 1935 Columbia University recording with spoken narrative

Lunsford’s subsequent recordings in the 1940s omit the “pistol” verse. In his liner notes about the song on the Smoky Mt. Ballads album, released by Folkways Records in 1953, he doesn’t mention African Americans or convicts as the “construction work hands” who “brought it to that section.” He restates and reinforces Sharpe’s claim that “it is a variant of an old English song.”

Bascom Lamar Lunsford "Swannanoa Tunnel" (1953)

During the 1960s, several folk music revival performers recorded versions of “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Through performance context and variations in lyrics, these tend to obscure further the song’s origins as an African American work song. Paul Clayton, a musician, and scholar who earned a master’s degree in folklore from the University of Virginia, recorded a version similar to Lunsford’s for his 1962 Folkways album Dulcimer Songs and Solos Sung and Played by Paul Clayton on the Southern Mountain Dulcimer.

Paul Clayton "Swannanoa Tunnel" (1962)

Erik Darling, who recorded and performed both as a solo artist and with The Rooftop Singers, released a version of “Swannanoa Tunnel” on his first solo album in 1958. He learned the song from fellow folk music revivalists in New York City. His version includes the stanza, “If I could gamble like Tom Dooley, I’d leave my home, honey, I’d leave my home.”

Erik Darling "Swannanoa Tunnel" (1958)

Bryan Sutton recorded a bluegrass version of “Swannanoa Tunnel” for his 2014 album Into My Own. His new opening stanza adds context to the song without mentioning African American convict laborers. “Train’s gotta run from Rowan County, the land’s run dry, baby, the land’s run dry. And how you gonna get that line over the mountain? Gonna dig right through, baby, gonna dig right through.”

Bryan Sutton "Swannanoa Tunnel" (2014)

Live performance videos by Sutton, and others by folk musician Willie Watson, can be found on YouTube. While the singers’ spoken introductions give the song some context, they do not mention the African American convict laborers who sacrificed their lives to blast the tunnel. Perhaps this article, the RAIL Project, and the sources listed in Further Reading will help bring daylight to the story of the men whose work brought daylight to Buncombe County through the Swannanoa Tunnel.

Lyrics

(adapted from multiple versions of the song)

I'm going back to that Swannanoa Tunnel

That's my home, baby, that's my home

Asheville Junction, Swannanoa Tunnel

All caved in, baby, all caved in

Last December, I remember

The wind blowed cold, baby, the wind blowed cold

Hammer falling from my shoulder

All day long, baby, all day long

When you hear my watchdog howling

Somebody around, baby, somebody around

When you hear that hoot owl squalling

Somebody dying, baby, somebody dying

Ain't no hammer in this mountain

Outrings mine, baby, outrings mine

This old hammer, it killed John Henry

It didn't kill me, baby, it couldn’t kill me

This old hammer rings like silver

Shines like gold, baby, shines like gold

Take this hammer, throw it in the river

It rings right on, baby, it shines right on

Some of these days I'll see that woman

Well, that's no dream, baby, that’s no dream

I'm going back to that Swannanoa Tunnel

That's my home, baby, that's my home

Sing It Yourself Videos and Recordings

Download or stream recordings from Bandcamp:

Lead Sheet

Download and print lead sheets that include lyrics, chords, and melody.

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Further Reading