by Rex Rideout

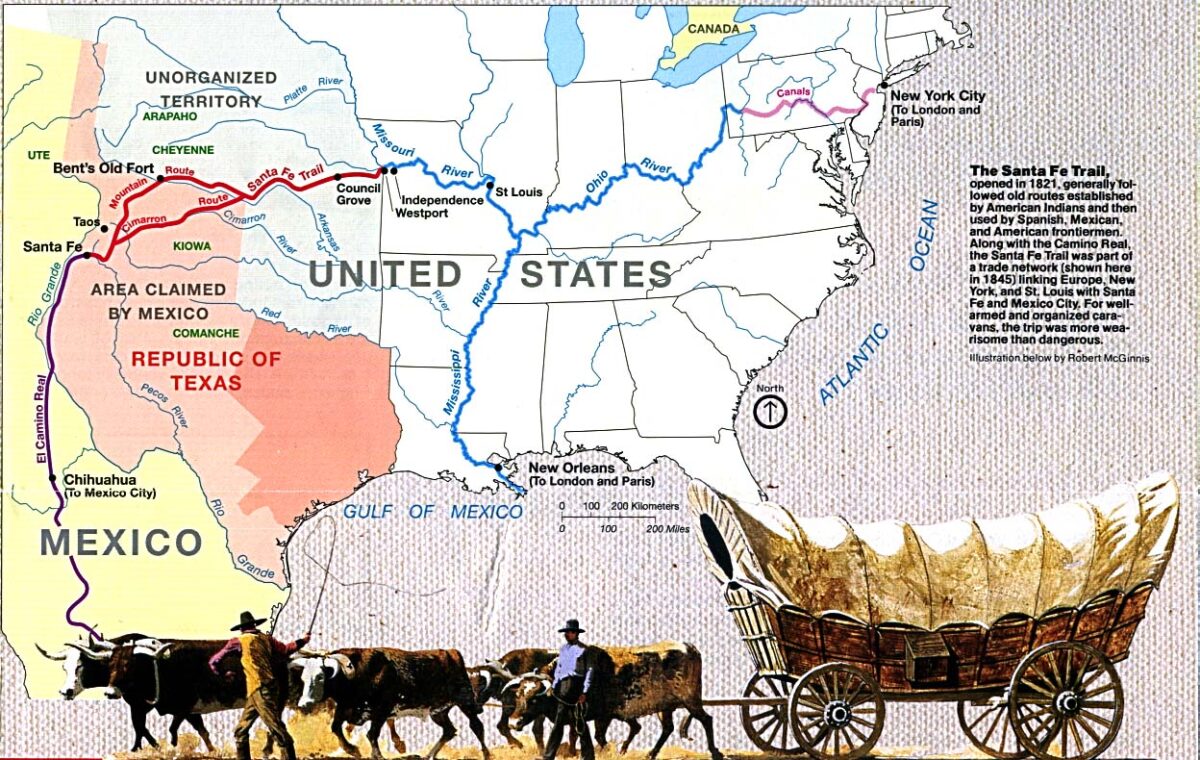

This article was originally published in Wagon Tracks, the official publication of the Santa Fe Trail Association, Volume 36, Number 4, May 2022. In 1821, the Santa Fe Trail became America's first great international commercial highway, and for nearly sixty years thereafter was one of the nation's great routes of adventure and western expansion.

Contents

It was in the summer of 1821 that Captain William Becknell and comrades headed for Santa Fe with goods loaded on pack animals. His actions and great success inspired commerce to ship to the isolated people in northern Mexico via a route that took on the name, the Santa Fe Trail. The dangers and hardships encountered by these would-be merchants inspired many stories and songs. Such danger, and the inspiration to write it all down, was greatest in the early years, but those stories continued even until the use of the trail was all but ended by the completion of the railroad to the region in 1880.

Those with the ability and nerve to travel along the Santa Fe Trail in its early days found a life of hardship and struggle from the elements, their own draft animals, and people already there defending their homeland. Any chance for relief was received with grateful hearts. Now and then, when the work was done, there was time for frolic and music. There are many tales told by those who made this journey and how joyous it was when someone let loose with a song or took up the fiddle.

Music has always been present along the Santa Fe Trail. This article will review the music heard along the trail in early times and how it changed with events, as did the trail itself, until its close by the railroad. Some of the songs and verse heard will be covered, as well as the instruments that would have been found, and in some cases, who was playing those instruments. The trail was a nexus of cultures and music as well. Musicians from the East were joined by those from the North, from the South, and the Native Peoples who were already there. Even after the trail closed, there were songs in praise of its challenge and those who dared to overcome it.

In the silence of the wilderness with camp made, guards set and the boys gathered around the fires inside the corral, the blue dome above, the flickering lights on the wagon covers and on our bronzed faces, the stage is set for oratory, song and jest.1

Those words are found in David Kellogg’s diary as his party is bound for Santa Fe in 1858. September 30 finds them encamped near Cow Creek along the Arkansas River and thirsting for adventure. A steady flow of wagons had come before them, and many would later follow. These were men who were willing to take risks and seek their fortune in the wild West. They had music as a close companion. Even the Corps of Discovery, a military expedition that set out in 1804, had violins and other instruments to entertain themselves and to aid in securing relationships with the native peoples they would meet. So did those who would follow; they carried instruments, as well as popular songs, cherished hymns, and old ballads from home. Some would also compose verses “in the saddle” as a way to recall new adventures. For those that would follow William Becknell, the first step was to cross that big muddy Missouri. It was as if they must cross the River Jordan to reach the promised land. Marc Simmons tells of his own impressions when seeing the Missouri from Franklin for the first time in his book, The Old Trail to Santa Fe.

There in Franklin, on my first visit, I looked westward past green-robed bluffs to the bottomlands leading down to the banks of the mighty Missouri River. And gazing across the dark waters, I imagined that I could see, in sequence, the many trail landmarks studding the route all the way to Santa Fe. Their colorful names, as familiar to me as to the wagonmasters, conjured up images of shouting teamsters, rumbling wagon wheels, and rattling trace chains.2

The following unadorned example of poetry or verse about the trail served a more urgent purpose. It was intended as a message requesting a mailwagon to hold its departure for Santa Fe. The message was sent October 27, 1853, as a telegraph by Captain Alexander W. Reynolds in Jefferson City, Missouri. He hoped to keep the mailwagon in Independence from departing for Santa Fe before his arrival. This mail-wagon was the only means of transport for that time of year and required the robust fee of 150 dollars. Captain Reynolds’ poetic communication venture was successful. He and fellow riders departed for Santa Fe on November 1, 1853.

Fink’s stages are so rickety,

His horses are so slow,

His drivers are such drunken sots,

They scarce can make them go.

Then hold your horses, Billy,

Just hold them for a day;

I’ve crossed the River Jordan,

And am bound for Santa Fe.3

It seems I am not the first to imagine crossing the Missouri as if it were the River Jordan. The following articles describe well those satisfying times when the work that must be completed that day was done, and the wagon party had some time to give thought to entertainment while meals were being prepared.

...the wagons being drawn up in a circle or semi-circle, and the mules cared for, the drivers give themselves up to enjoyment. Some go out for a chance at a deer or other game, others take to card-playing, and the musical ones of the party make the camp lively with their rude strains.4

The camp cooking fires are lighted, and during the preparations for the meal, which includes both dinner and supper, the hearts of the weary wagoners are beguiled with cheering notes from the musician of the train.5

Following a successful venture to Santa Fe in 1845 and selling his goods at a handsome profit, James Josiah Webb observed that it was early in November and time to return to the States. In time he learned that he might have been better off to have left earlier. Webb and a small party departed for St. Louis with a muledrawn wagon loaded with 40 bushels of corn, and four thousand dollars in gold dust hidden out of sight. They encountered only the usual difficulties until they approached the Arkansas River with the intent of crossing but found it iced over. They attempted to chop their way through with axes but were unable; they couldn’t cross. Webb wrote that there was “snow and very high wind.” The party stopped to consider their options. Meanwhile, the cook was preparing a meal and began to sing "Home Sweet Home" as he worked. Webb questioned his musical selection. “The thought of the comforts of home, and loved friends around the cheerful fireside with no apprehensions of danger from enemies or suffering from cold or hunger, contrasted with our situation... , was too much. And I called him to order and offered a resolution that any member of the company who, during the balance of the trip, should sing any song of home or speak of the good things of home or of the comforts of home, should be fined a gallon of whiskey payable on our arrival at Westport." 6

If there were any further musical misadventures during the trip, there was no mention of them. Webb’s resolution seems to have impressed his companions. George Ruxton tells of encountering a Mormon camp along the Arkansas River near the Rocky Mountains in 1847. In time a dance was called for.

On such occasions, someone in the camp would have to be relied upon to provide the music. It would appear that Brother Ezra was a man you could depend on. “After saying thus, he called upon brother Ezra to ‘strike up’: sundry couples stood forth, and the ball commenced. Ezra of the violin was a tall shambling Missourian, with a pair of homespun pantaloons thrust into the legs of his heavy boots. Nodding his head in time with the music, he occasionally gave instructions to such of the dancers as were at fault, singing them to the tune he was playing, in a dismal nasal tone,-- ’Down the center--hands across, You Jake Herring--thump it, Now, you all go right ahead-- Every one of you hump it. Every one of you--_hump it_.’ The last words being the signal that all should clap the steam on, which they did _con amore_, and with comical seriousness." 7

Music on the trail was by necessity homespun, and a desire for entertainment was to be satisfied even if musical instruments were not at hand. I have read many first-person accounts of how one enjoyed a good meal in a tavern and then rested by a comforting fire while someone played tunes he enjoyed on a fiddle or banjo. But just what those tunes were is frequently overlooked. The following is from a personal journal of Isaac Cooper, who was part of Fremont’s 3rd expedition in 1845. Here we learn of at least two songs that were popular among Cooper and his companions.

Indeed we were all in an admirable condition to speculate on matters and things- for at the tavern of Westport all hands made a simultaneous rush at the bar and the whole crew one and all, by the time we left the town which we did with extraordinary eclat yelling & shouting- were in a most pitiable condition of gloriousness, and adapted in every way to well appreciate the beauty of lanscapes and to poetize theron. 'Old Dan Tucker’ that well patronized air and ‘Lucy Neal’ were sung with rapture, and with a strain of most mournful music proceeding from our throats in the shape of some 5 or 6 different songs at once- our little waggon whirled into the Camp.8

Marian Russell has fond memories of music on the trail in 1848 and hearing her mother sing. “At times I seem to see her standing by a flickering campfire in a flounced gingham dress and a great sunbonnet. Behind her looms the great bulk of a covered wagon. I think I can hear her singing, Flow gently sweet Afton, Among thy green braes.” She recalls Mr. Mahoney, “I remember that he would play the banjo and sing Irish ballads with a good strong voice with a rollicking note in it.” Much later she recalls of being several days from Fort Leavenworth on the trail in 1860 and still there was music. “We drove with us a heard of horses and cattle and for that reason made haste slowly. Singing and shouting went on all around us. From a wagon ahead of us a violin was usually wailing." 9

Lewis Garrard had admiration for his companions on the trail even if their culture was foreign to him. Music needs no translation: “There were eighteen or twenty Canadian Frenchmen (principally from St. Louis), composing part of our company, as drivers of the teams. As I have ever been a lover of sweet, simple music, their beautiful and piquant songs, in the original language, fell most harmoniously on the ear, as we lay wrapped in our blankets.” And later after crossing the Cimarron: “One of the Mexicans — a dreamy looking fellow of twenty-two or three years of age — sang in a low, dulcet tone, in his own harmonious, flexible language, melodies of a plaintive, yet pleasing character; indicating by the expression of his countenance, the sentiment of the song.” Upon his arrival to Bent’s Fort, Garrard recalled the “rudely-scraped tune, from a screaking violin” as the primary source of music for the dances. He leaves us with a vivid picture of how the fort’s occupants could raise the roof when time and circumstance allowed for it. “They nightly were led to the floor ‘to trip the light fantastic toe,’ swung rudely and gently in the mazes of the contra dance – but such a medley of steps is seldom seen out of the mountains – the halting, irregular march of the war dance; the slipping gallopade, the boisterous pitching of the Missouri backwoodsman, and the more nice gyrations of the Frenchmen – for all, irrespective of rank, age, and color, went pellmell into the excitement, in a manner that would have rendered a leveler of aristocracies and select companies frantic with delight. It was a most complete democratic demonstration." 10 George Bent recalls another instrument at Bent’s Fort, the banjo as played by his friend, Frank P. Blair. “They often had balls at the fort, and Blair would sit up all night playing the banjo in the ‘orchestra’." 11 There is more evidence of music at Bent’s Fort. Recovered from the fort’s trash dump were both a Jew’s-harp frame and a reed from a harmonica.12 And as for that violin, Bent, St. Vrain & Co. was billed for violin strings in an 1838 invoice.13

James Bennett writes that while camped on Ocate Creek near Rayado in autumn of 1854, they are joined by 1st Dragoons on their way to Fort Union. Even while far from the comforts of civilization, their regimental band still delivered an impressive performance. And fortunately, Bennett remembered two of the tunes. “Col. T. T. Fauntleroy arrived from the United States Friday with 200 recruits, Companies B and H, 1st Dragoons; the band belonging to the Regiment; 300 horses; 150 wagons; etc. The band came out and played today. They were all mounted on black horses. They looked fine and played well. This is the first brass band I have heard since 1850. The first tunes played were ‘Old Folks At Home’ and ‘Sweet Home’.” 14

There is one song that seems to singularly represent the great venture of making one’s way into the wild West. Bernard DeVoto offers a nod to it on the frontispiece of his book, Across The Wide Missouri. There he presents the complete words to “Shennydore” with no explanation why or any other mention of the song within those pages.15 Four years later, MGM released the film Across the Wide Missouri in 1951, starring Clark Gable as Flint Mitchell and Ricardo Montalban as Ironshirt. The screenplay was based on DeVoto’s book. The soundtrack included new words and music for "Across The Wide Missouri" and of course, the traditional "Shenandoah." 16

What of this Shenandoah? It seems to be more of myth than history. Yet David Bone, the author of Capstan Bars, gives it some authenticity as an actual sea chanty. “I have never heard this song sung at other duty than weighing anchor.... The very beauty of the air has even curbed the license of wild singers in the text. No bawdy lines, no plaint of mistreatment, no blasphemous exhortations were ranted in the singing of it." 17 But just how old is this song? It appears in Sailors’ Songs, The Riverside Magazine for Young People which dates it to 1868.

Oh, Shannydore, I long to hear you!

Chorus.-- Away, you rollin’ river!

O, Shannydore, I long to hear you!

Full Chorus.--Ah ha! I’m bound away

On the wild Atlantic! 18

It is none other than General William Jackson Palmer, the founder of Colorado Springs and much more in the Rockies, that places this song firmly in the middle of the nineteenth century. Having been sent to England to study railroads and coal mining, he writes of his return voyage to New York in May of 1856. He finds five days of head winds maddening, when - “but a short favorable run of 20 hours would ‘tie us up by the nose’ in the North River, or, as the sailors say

in their songs ‘Run her into clover.’” He recalls the sailors’ songs and shanties to be, “musical but after a certain wild mood that is very appropriate to the words and the scene: ‘Hi, yi, yi, yi, Mister Storm roll on, Storm Along, Storm Along,’ or ‘All on the Plains of Mexico,’ or the wildest and prettiest of all, which ends - ‘Aha, we’re bound away, on the wild Missouri’.” 19

David Bone and others say this song was used as a capstan and sometimes a halyard chanty and was generally sung when they were returning to their home port. So Shenandoah was an actual sea chanty sung at work on sailing ships. But did it make its way inland, even to the Santa Fe Trail? It is said to be a song belonging to the U.S. Cavalry and yet any real evidence to back this up is scarce. I once snapped up sheet music with the title: "Shenandoah A Trooper’s Song." I learned that this was a song in praise of the Army of the Shenandoah and first sung to honor an officer of the Army of the Potomac. While I am happy to have this music in my collection, it was not the missing link I was searching for.20 Carl Sandburg’s The American Songbag, includes “The Wide Mizzoura.” Sandburg writes in its introduction, “Regular army men were singing this in 1897." 21 John Lomax writes in American Ballads and Folk Songs that “The Wild Miz-zou-rye” is an “Old Cavalry Song”.22 The Wide Mizzoura,” “The Wild Miz-zou-rye,” could it be that these alternate titles are to avoid confusion with the above “Shenandoah, A Trooper’s Song?” Edward Dolph writes of this song having the name, For Seven Long Years in Sound Off! Soldier Songs. “The cavalry jealously claims this song for its very own, having acquired it, no doubt, during the frontier days. Sometimes the ‘would not have me for a lover’ stanza is followed by one beginning, ‘Because I was a wagon soldier’; but the cavalry claims this to be a field artillery intrusion and an attempt to steal its song." 23

An article in the July 12, 1915, Chicago Tribune by Floyd P. Gibbons tells of an overnight march by the 1st Cavalry of the Illinois National Guard. The soldiers were singing while marching through the darkness. “The troopers took up the refrain of the marching song used by the old Seventh United States Cavalry during the years that it was in the Indian service along the Missouri river.”

For seven long years, I courted Nancy.

Hi-oh, the rolling river.

She wouldn’t have me for a sweetheart.

Ha, ha. We’re bound away for the wild Missouri.

Because I was a cavalry soldier.

Hi-oh, the rolling river....

“We learned this song from Tommy Tompkins, Hi-Oh, ... Tompkins of the Fifth cavalree." 24

This is very close to the words as collected by Lomax even to the mention of Tommy Tompkins but only in this source is he associated with the 5th Cavalry. Here I want to add that there are about 200 written versions of the old ballad Barbara Allen. I’ve found four that have the line, “I courted her for seven long years.” It makes one wonder if there is some long ago connection between Shenandoah and Barbara Allen but I will leave that for another study.

John Lomax appears again in an article within the U.S. Cavalry Journal in 1910. On his behalf, the editor of the journal is asking readers to send in their old campaign songs. Once again the Wild Missouri is remembered. “Professor Lomax asks that our readers send in copies of old army songs or any relating to the military life of the soldier. ...and it is possible that in another generation even the ‘Wild Missouri’ will be a thing of the past." 25 At last I found what I was looking for, a solid connection between Shenandoah and the Cavalry. It was the 7th Cavalry, as stated by the Army itself in the Army and Navy Register, 1907. “...The officers assembled then sang an old regimental song of the 7th cavalry, “The Wild Missouri. ..." 26

I was hunting through a used book store some years ago and found one of the most complete sources for this song as “The Wide Missouri” in a tattered copy of Chowder Melodies - Sea Chanties & Other Songs of the Plains. Within were six complete verses beginning with the following:

For seven long years I courted Nancy--

Hi-ho! The rolling river!

For seven long years I courted Nancy--

Hi-ho! I’m bound away for the wide Missouri! 27

These words are identical to those credited to the Seventh United States Cavalry when in the Indian service along the Missouri River. I wish I could know where the collectors of Chowder Melodies found their songs. Maybe they met an old Cavalry officer. The above sources confirm that "Shenandoah" did find its way inland even to the Southwest and the old trail. All of these sources date to the beginning of the 20th century and tell of it being at the time an old song, easily reaching back to the time of the Santa Fe Trail. It was carried horseback with the 5th and 7th Cavalry and as it was sung with feeling, was heard by other inhabitants of the West. "Shenandoah," "Dan Tucker," and "Home Sweet Home" were sung around many a lonely campfire along the trail. They pushed back the darkness and made the long journey a bit more bearable. In turn, they add a bit more color to the stories we have today of those who braved the Santa Fe Trail.

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Notes

1. David Kellogg’s Diary, Society of Sons of Colorado, The Trail, December, 1912.

2. Simmons, Marc, The Old Trail to Santa Fe, (University of New Mexico Press, 1996), xiii - xiv.

3. Davis, William Watts Hart, El Gringo; or, New Mexico and Her People, (Harper & Brothers, 1857), 14.

4. Cary, William M., “The Train Encamped,” Hearth and Home, Feb. 25, 1871, 148.

5. Pilgrims of the Plains, Harpers Weekly 12-23-1871, 1200.

6. Webb, James Josiah, Adventures in the Santa Fé Trade, 1844–1847. (University of Nebraska Press - Bison Books 1995), 159.

7. Ruxton, George, In the Old West 1845 (Outing Publishing Company 1915).

8. Fremont 3rd exp 1845, Journal of Isaac Cooper (Francois des Montaignes).

9. Russell, Marian, Land of Enchantment, (Branding Iron Press, 1954) 2, 5, 78.

10. Gerrard, Lewis H. Wah-To-Yah, and the Taos Trail 1846 (University of Oklahoma Press 1955), 11, 74, 149.

11. Hyde, George, Life of George Bent (University of Oklahoma Press 1968), 84.

12. Bent’s Old Fort NHS archives.

13. Ledger Z, Pierre Chouteau Jr. & Co., Fur Trade Ledger Collection, Missouri History Museum.

14. Forts and Forays James A. Bennett: a Dragoon in New Mexico 1850-1856, (University of New Mexico Press, 1948).

15. DeVoto, Bernard, Across The Wide Missouri, (Houghton Mifflin, 1947).

16. Across the Wide Missouri (1951), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

17. Bone, David William, Capstan Bars, (Porpoise Press 1931), 105.

18. Sailors’ Songs, The Riverside Magazine for Young People (April 1868), 185.

19. Fisher, John Stirling, A builder of the West; the life of General William Jackson Palmer, (Caxton printers, 1939), 49.

20. Shenandoah A Trooper’s Song, 1896, (Oliver Ditson Company).

21. Sandburg, Carl, The American Songbag (Harcourt, Brace and Company 1927), 408.

22. Lomax, John, American Ballads and Folk Songs, (The MacMillan Company1934), 544.

23. Dolph, Edward Arthur, Sound Off! Soldier Songs, (Cosmopolitan Book Corporation 1929), 4.

24. Gibbons, Floyd P., "It’s a Wild Life, a Cavalry Ride, in Mud and Dark, Troopers Get Taste of Real Soldiering on Thirty Mile Forced March." Chicago Tribune July 12, 1915.

25. Army Ballads, U.S. Cavalry Journal July 1910, 204, 205.

26. Notes from Fort Riley, The Army and Navy Register, Oct. 19, 1907, 167.

27. Chowder Melodies - Sea Chanties & Other Songs of the Plains, The General Miles Marching