Contents

This article focuses on the blues queens of the 1920s. For a general overview that follows the evolution of blues music from its origins through its contemporary forms, see Blues: About the Genre.

Overview

In the 1920s, African Americans enjoyed unprecedented success in the record industry. They had made recordings since Thomas Edison’s phonograph became widely available in the 1890s, but companies dictated that African Americans record primarily "coon songs" (see Ragtime) and minstrel show material that reinforced black subservience. Through blues and jazz in the 1920s, African Americans took center stage with music from their own cultural heritage as record companies propagated the growth of a "race records" market that sold music by black artists to black listeners.

In the decades following emancipation, African Americans living in the South developed blues music from earlier folk forms (see Birth of the Blues). Starting with W.C. Handy's "The Memphis Blues" in 1912, a more formalized blues became popular throughout the United States. Sheet music and recordings sold well, and dance bands performed the hits nationwide. However, only white vaudeville singers and instrumental ensembles were recording blues. This all changed in 1920 when the first blues record released by an African American singer became an instant nationwide hit.

Mamie Smith and "Crazy Blues"

Around the turn of the twentieth century, communities across the United States experienced changes to their racial and ethnic demographics as the nation welcomed new immigrants, experienced internal migrations, and expanded the fringes of the nation’s ethnic tapestry. New groups of immigrants gained legal rights and privileges as legally “white” even as they continued to face prejudices. As household incomes in immigrant neighborhoods increased, businessmen saw opportunities to open new markets for their products. In the late 1910s, record companies successfully targeted ethnic communities with Italian, Polish, Spanish, and Yiddish language recordings.

Perry Bradford, a black composer and publisher, believed that black consumers would purchase records by African American artists if they were made available. Black workers had been migrating from the South in large numbers to fill factory jobs in the North, Midwest, and West since the outbreak of World War I in 1914. As many migrants found more stable living conditions and employment options, they also found new social challenges and novel racial spaces. African American communities formed in cities such as New York, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. While wages were low and working conditions poor, many saw a regular paycheck for the first time in their lives.

Bradford convinced Okeh Records to record a black vaudeville and cabaret singer from Harlem named Mamie Smith. On February 14, 1920, Smith, backed by an all-white orchestra, recorded two non-blues compositions by Bradford. Okeh issued them, and sales numbers showed promise. Smith returned to the studio on August 10 to record two more Bradford compositions. This time, a band of black jazz musicians backed her up. They recorded "Crazy Blues" and "It's Right Here for You." The record, credited to Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds, featured "Crazy Blues" as the A-side. It was the first blues record released by an African American singer. Popular with both black and white audiences, “Crazy Blues” was one of the biggest-selling records of the year.

Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds "Crazy Blues" (1920)

Smith was the first black recording artist marketed to black record buyers. Bradford's experiment was an overwhelming success, awakening the entertainment industry to a vast potential market. Okeh and other labels rushed to find and record African American singers. Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Edith Wilson, Sara Martin, and Lucille Hegamin released blues records by the end of 1921.

Pace Phonograph Company, which issued records on the Black Swan label, represented the first major record company to be owned by African American entrepreneurs. Black Swan enjoyed tremendous success in the spring of 1921 with the release of Ethel Waters' "Down Home Blues" and "Oh Daddy."

Ethel Waters "Down Home Blues" (1921)

Harry Pace founded the label in 1921 after dissolving the music publishing company he had co-owned with W.C. Handy. Waters and Alberta Hunter were versatile vaudeville and cabaret singers who released blues records on Black Swan, which also released records by African American classical musicians and dance bands.

Alberta Hunter "He's a Darn Good Man (To Have Hanging Round)" (1921)

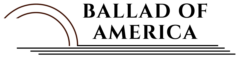

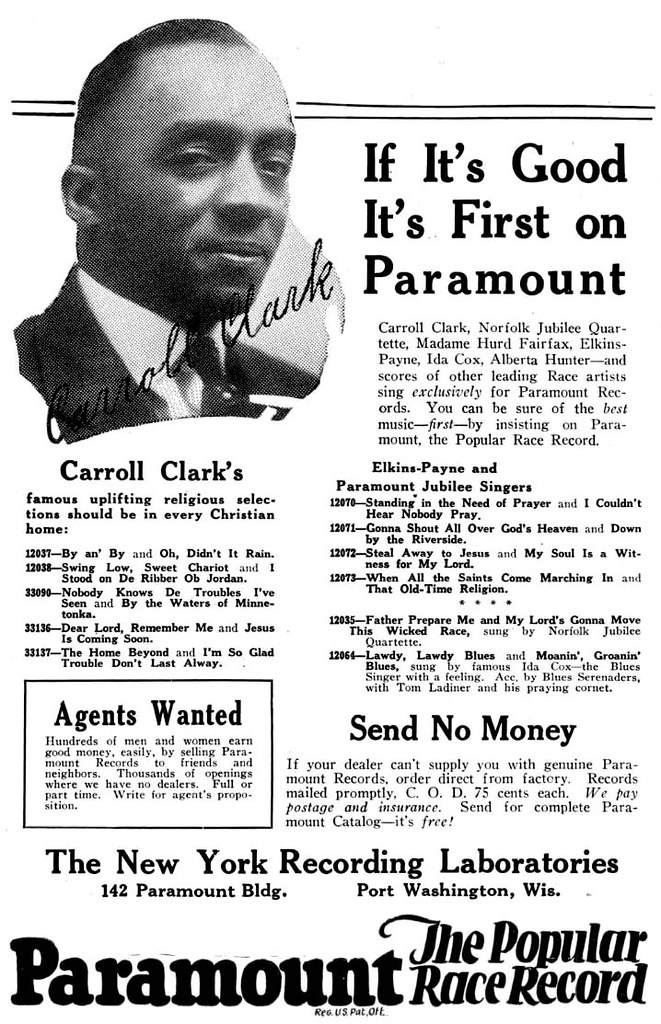

Race Records

Eager to build on the success of their black blues records, companies began organizing their catalogs in a new way. In the summer of 1921, General Phonograph Company, which issued the Okeh label, launched its Original Race Records series. Starting with series number 8001, Original Race Records issued recordings of black blues, jazz, and religious sermons. Other companies created their own race records series, including Columbia, Paramount, Vocalion, and Victor.

Before the advent of race records, companies marketed all different music styles in one catalog, separating only classical music. They made and sold records aligned with their perception of the tastes of the urban middle class, primarily vaudeville, Tin Pan Alley, brass bands, classical, opera, and Broadway. The new race records applied the principles of ethnic niche markets on a much grander scale.

In 1923, Okeh led the way again, starting a separate series that featured records by white rural Southern artists marketed to a similar consumer group. Other labels followed suit, creating new catalogs under names such as "hillbilly," "old-time," or "old familiar tunes." These catalogs paralleled the segregation in society and obscured the musical interaction that had long occurred among blacks and whites.

Both race and hillbilly series included various styles, but only to the extent that the music fit the companies' notions of "black" and "white" music. They did not release fiddle breakdowns in race record catalogs, even though they had traditionally been part of many black musicians' repertoires. Record companies occasionally issued a record by a black artist in the standard pop catalog, but only if they believed it would appeal to white customers. Some black artists found their way onto hillbilly records, although generally as uncredited members of backing bands.

African American blues queens were race records' biggest stars. The first wave included Mamie Smith, Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Lucille Hegamin, Trixie Smith, Edith Wilson, Sara Martin, Victoria Spivey, Sippie Wallace, and many others. These early blues queens did not specialize in blues. They were versatile theater and cabaret singers who performed a variety of popular music styles. For their race catalogs, the labels wanted blues, and that’s what they captured on record. The vocal delivery of these artists, though, was not unlike that of the numerous white performers who released successful blues records during the previous decade (see Birth of the Blues).

Southern Blues Specialists

In May 1923, Bessie Smith made her first recordings for Columbia. She sang "Gulf Coast Blues" and "Down Hearted Blues." The latter had been a hit the previous summer for the song's co-composer, Alberta Hunter. Smith's release of "Down Hearted Blues" sold a million copies within a year.

Bessie Smith "Down Hearted Blues" (1923)

Unlike Hunter and the rest in the first wave of blues queens, Smith hailed from the South and specialized in the blues. She got her start busking on Chattanooga's streets as a child after the death of her parents. In 1912, at the age of 14, Smith joined a professional traveling troupe that included the singing star Gertrude "Ma" Rainey. For a decade, Rainey had been adapting the folk blues she encountered in the South and incorporating it into her stage act with great success (see Birth of the Blues). Rainey, who would become known as "Mother of the Blues," mentored the younger, less-experienced Smith in matters of stage presence, style, and life on the road.

Following her hit "Down Hearted Blues," Smith became the most famous and successful blues singer. Known as "Empress of the Blues," she recorded and toured extensively until the Great Depression dampened the music industry. In 1929, Smith starred in a 16-minute film called "St. Louis Blues." The film dramatized W.C. Handy's most enduring song, which he published in 1914. Handy produced this early sound film and asked Smith, who had a hit with the song in 1925, to star in it.

Bessie Smith "St. Louis Blues" (1929)

Smith's initial success in the spring of 1923 prompted record companies to seek out other Southern blues specialists. Her mentor, Rainey, made her first recordings later that year. Unlike the Northern singers, who recorded the latest compositions by professional songwriters, Rainey had a repertoire of songs she picked up over two decades of successfully singing the blues across the South.

Ma Rainey "Moonshine Blues" (1923)

Other singers in the Southern wave included Clara Smith, Ida Cox, and Sippie Wallace. They brought "deep blues" vocal styles rooted in older black folk traditions, traceable back to Africa (see Birth of the Blues). Echoes of sorrowful plantation field hollers and moans were evident in their voices. To many Northerners, these singers came across as unappealing and old-fashioned. Black Swan had passed on the opportunity to record Bessie Smith because she was "too gritty." These Southerners sang some of the same songs as the Northern blues singers, but they also recorded songs reflecting rural experiences, such as boll weevils destroying cotton crops and drinking moonshine whiskey.

Ida Cox "Any Woman's Blues" (1923)

Significance

With increasing middle-class prosperity, the 1920s saw a rise in consumer-oriented culture. As buying on credit became the norm, families purchased new, or newly-affordable, technologies such as cars, washing machines, refrigerators, radios, and toasters. Women, both black and white, enjoyed new means of self-expression during the decade that started with being granted the right to vote. Some paid more attention to clothing and cosmetics, wore scandalously short dresses, men’s hats, and smoked cigarettes. Women, and men, enjoyed the new freedoms afforded by developments in birth control and its gradual acceptance in society.

The blues queens embodied these changes in society. They were glamorous pop stars who performed and appeared in photographs wearing glitzy dresses and jewelry. They headlined large shows that included dancers, comedians, and other entertainers. It was a significant leap forward for African American entertainers in a time of intense racism and segregation. No longer beholden to the tropes of minstrelsy, blues queens presented themselves as sophisticated professionals. Race records advertisements sometimes included minstrel imagery, but many featured realistic portraits of the artists.

Thomas "Fats" Waller, Charles Warfield, Clarence Williams, Perry Bradford, Alex Hill, and Chris Smith were among the African American professional songwriters who wrote hits for the blues queens. In the 1910s, white vaudeville singers who recorded blues sought material by black composers to give them authenticity. In the 1920s, white composers sought authenticity by having black singers record their songs. Several blues queens, including Ma Rainey, Victoria Spivey, Bessie Smith, and Ida Cox, wrote or co-wrote some of their songs.

For the first time in the professional music industry, African Americans sang about issues relevant to their own lives and the lives of their core audience – black women. They sang of economic hardship, bad luck, and travel. Most commonly, they explored the contours of love and romantic relationships. Lyrics examined jealousy, cheating, revenge, physical pleasure, and abuse with unflinching candor. Though the singer was often the victim in a bad relationship, they might also seize control of their destiny. While mainstream popular music favored notions of romantic love, African American women celebrated sexual independence with unparalleled frankness. As Bessie Smith sang, "No time to marry, no time to settle down, I'm a young woman, and ain't done running 'round.”

The blues queens generally had a small jazz ensemble backing them. It was the jazz age, and many songs and recordings defied clear delineation between the two genres. Ma Rainey, one of the earthier performers, occasionally included rural instrumentation, such as banjo, guitar, and jug band. Record companies had established the blues queens' basic style by 1924 and began seeking new variations to excite sales. In January, Okeh Records released "the first blue guitar record," featuring singer Sara Martin backed only by Sylvester Weaver's "big, mean, blue guitar." The record was marketed with a hand-drawn country scene featuring an old black man playing guitar in front of a shack. It was a far cry from the glamour of the blues queens and an indicator of the next popular trend in blues music – country, or rural, blues.

Solo singer/songwriter/guitarists, such as Charley Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and later Robert Johnson, did not reach the heights of the blues queens' success. However, they had a more significant impact on later blues revivalists and in the evolution of rock and roll.

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Further Reading

Crawford, Richard. America’s Musical Life: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Gioia, Ted. Delta Blues: The Life and Times of the Mississippi Masters Who Revolutionized American Music, 2009.

Jones, Leroi. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Harper Perennial, 1999.

Miller, Karl Hagstrom. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Milward, John. Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock ’n’ Roll. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2013.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Wald, Elijah. Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. New York: Amistad, 2004.

Wald, Elijah. The Blues: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.