Overview

Spirituals are African American religious songs that evolved in the context of slavery primarily in the Southern United States. They were a mechanism for survival – a potent example of how humans can endure the worst of conditions. Spirituals combine elements of European American religious music with African musical characteristics. Their influence can be felt in virtually all subsequent forms of American music, including jazz, gospel, blues, rhythm and blues, country, rock and roll, and hip-hop.

Music in Africa

Most people who came to America in slavery were taken from the west coast of Africa. While they hailed from a wide variety of kingdoms, states, city-states, clans, tribes, and kinship groups, music was integral to everyday life throughout the region. “We are almost a nation of dancers, musicians, and poets,” writes Olaudah Equiano, one of the first Africans to write a book in the English language.

Through the slave trade, elements of music and dance traditions from Africa were integrated into American culture. This includes African musical and performance characteristics that were elemental to spirituals. Both musics were very emotional. The singing was often highly intense and included falsettos, shouts, and groans. There was call and response singing, with a song leader singing a phrase and the rest of the group singing a reply. Refrains were repeated and sung as choruses. Percussive sounds were added with handclaps and foot stomps. Words were improvised. Dancers shuffled in ring formations.

European American Religious Music

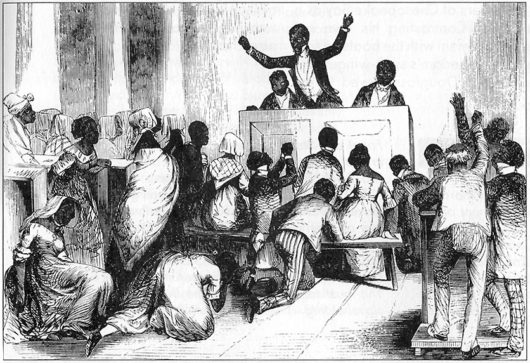

Early Protestants in the New World sang a type of religious song called a psalm. Psalms had lyrics that were taken directly from biblical scripture. They were sung at a slow tempo without instrumental accompaniment. In New England during the colonial era, some African Americans attended Sabbath services in segregated seats and joined in the singing of psalms. Psalm singing was sometimes led by a precentor who "lined out" the psalm and "set the tune" so that those who couldn't read or didn't have the psalm book could join in the singing. The most popular early psalter was the "Bay Psalm Book," first published in 1640. It was the first book printed in the English colonies.

"Psalm 100," also known as "Old Hundred" was one of the best known and most commonly sung psalms.

In the 1730s and 1740s, a series of emotional religious revivals called the Great Awakening swept across the American colonies. Along with the Great Awakening came a new, livelier form of religious song called a hymn. While the words to psalms came directly from the Bible, hymns were religious poems based on scripture. English minister Dr. Isaac Watts published the book "Hymns and Spiritual Songs" in 1707. The book was very popular in the colonies, especially with African Americans. The new hymns gradually replaced the old psalms among the Protestant denominations.

African Americans and Christianity

People in the American colonies disagreed over whether to encourage, discourage, enforce, or prohibit the conversion of African Americans to Christianity. In the North, Christian denominations generally supported and facilitated conversion. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), the Church of England's missionary organization, formed in 1701 to convert African Americans to Christianity. They founded schools, including one at New York's Trinity Church, to provide religious instruction, which included psalm singing. Schools that taught Christianity and psalm singing also formed that were independent of established churches.

In the South, religious conversion was much less common than in the North. Large plantations were relatively isolated, and it was up to individual plantation owners whether or not to convert their slaves. Some believed that religious instruction made enslaved people “proud, and not as good servants." Others used passages from the Bible to justify the existence of slavery. They attempted to leverage these passages to make slaves more docile and subservient. After some people in slavery used their status as Christians to argue for their freedom, Virginia and other states passed laws specifying that baptism does not bring freedom to blacks.

The SPG was active in the South, and the Church of England had a strong influence on Southerners. Some slaves attended church with their masters. They sat in segregated galleries, on the floor, or listened from outside through an open window. The Reverend Samuel Davies, a Presbyterian minister from Virginia noted in 1751 that he was able to attract African Americans to his ministry through congregational singing. "The Negroes, above all the Human Species that I ever knew, have an Ear for Musick, and a kind of extatic Delight in Psalmody; and there are no books they learn so soon or take so much Pleasure in." The songs and hymns of Dr. Watts were favorites.

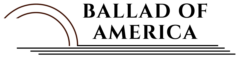

Black Churches

When worshiping in white churches, African Americans were generally segregated and subject to discrimination. By the late 18th century, African Americans began forming their own congregations that were part of the established churches. Whites were divided over their support of separate black congregations. The First African Baptist Church at Savannah, Georgia, formed in 1788. It was the earliest permanent African American congregation in the United States. Blacks in the South formed other congregations, generally Baptist. By the 1790s, there were separate black congregations in the North, most of which were Methodist.

Particularly in the South, most black congregations had white ministers and were governed by white councils. Following the Denmark Vesey uprising in 1822 and the Nat Turner insurrection in 1831, most black congregations were dissolved. As both revolts were led by preachers, whites placed blame on religious organizations. After the Civil War, blacks again formed independent congregations in the South.

In 1784, Old St. George's Methodist Church in Philadelphia issued former slave Richard Allen a preaching license. He was one of the first two black men to receive such a license from the Methodist Church. To overcome the discrimination blacks faced in white churches, Allen organized the first congregation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in 1794.

In 1801 Allen published a hymnal for the AME Church. "A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns Selected from Various Authors by Richard Allen, African Minister" included 54 hymn texts without tunes. Many of these were drawn from the hymnals of Dr. Watts and other favorite Methodist and Baptist hymnals. Others had been in oral circulation, and some may have been original Richard Allen compositions. The book is invaluable as a reference of songs that were favorites of African Americans before and after it was published.

"A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns" was the first song collection published expressly for a black congregation. The hymnal is also significant because it included refrains that both supported and contrasted with the message in the stanza. Refrains can be found in only one previous hymnal. Sung as a call and response, they were an element of African music that became common in later spirituals. Some refrains appeared in more than one song. Wandering refrains such as this appear to be unique to African American singing at the time. They were also frequently found in later African American spirituals.

The spiritual “My Lord, What a Morning” is an adaptation of a hymn from Allen's “A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns.”

Despite the relative freedom enjoyed by the independent black congregations, they were still controlled by white elders and subject to discrimination. In 1816, following a battle in court, several black Methodist congregations separated from the church and established the African Methodist Episcopal Church as the first black denomination. As the Church's first bishop, Allen published a new hymnal in 1818. It was larger than his previous hymnal and still contained favorites by Dr. Watts and others.

Many of these hymns would soon become favorites at the camp meetings of the Second Great Awakening. These camp meetings would provide fertile ground for the further development of spirituals.

Camp Meetings and Spiritual Songs

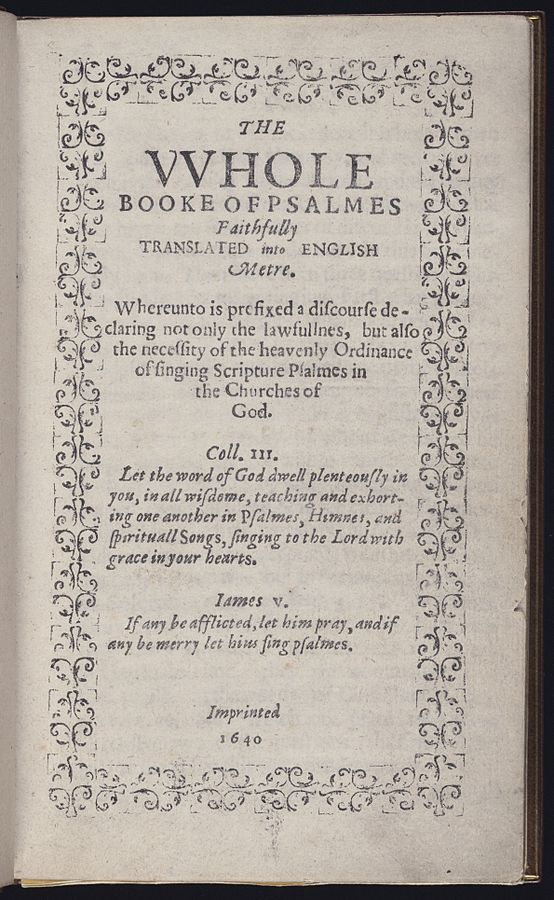

The Second Great Awakening was a religious revival that occurred roughly from the 1780s through the 1850s. Initially, it was led by Evangelical Protestant preachers. After the first few decades, Baptist and Methodist preachers became active leaders of the movement.

Outdoor religious services called camp meetings were one of the most common ways to preach the revival message during the Second Great Awakening. Camp meetings were held in tents in the countryside, on the frontier, or in the backcountry. They could last for days and include thousands of participants. The participants, mostly rural farmers and their families, sang and prayed in a large tent and often slept in smaller tents nearby. Camp meetings were highly emotional events with preaching about sin and Jesus as the only path to save one's soul from the fires of hell.

African Americans took part in camp meetings, even in slave states, though often in segregated sections. Some black ministers preached at the meetings. In 1818 the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church held the first camp meeting organized by and for African Americans. Other black churches, primarily Methodist and Baptist, sponsored camp meetings throughout the 19th century.

There were generally no hymnbooks in the early years of camp meetings. People sang from memory or learned songs at the meetings. From the energetic, highly emotional, noisy atmosphere of the meetings, a new kind of hymn and style of singing emerged.

Camp-meeting hymns sometimes used popular or folk song melodies to accompany isolated lines from prayers and scriptures. They often incorporated call-and-response singing, with a leader singing a verse and the congregation joining on the chorus or refrain. The new hymns also had wandering refrains and verses that appeared in multiple songs. Both call-and-response singing and wandering refrains were African American innovations that first appeared in print in Richard Allen’s “A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns.”

Contemporaries wrote about differences between traditional European American and African American religious singing. A report from an 1838 camp meeting held in Pennsylvania noted, “Their shouts and singing were so very boisterous that the singing of the white congregation was often completely drowned in the echoes and reverberations of the colored people’s tumultuous strains.” Swedish novelist Fredrika Bremer wrote of a camp meeting in Georgia, “A magnificent choir! Most likely the sound proceeded from the black portion of the assembly, as their number was three times that of the whites, and their voices are naturally beautiful and pure.”

More than a dozen writers reported that African Americans sang long into the night on their own segregated "shouting-ground" after other participants had gone to bed. Wesleyan Methodist John F. Watson was disdainful about African American singing practices, but his 1819 writings are very informative. According to Watson, “In the blacks’ quarter, the coloured people get together, and sing for hours together, short scraps of disjointed affirmations, pledges, or prayers, lengthened out with long repetition choruses. These are all sung in the merry chorus-manner of southern harvest field, or husking-frolic method, of the slave blacks.”

Watson is describing the performance of songs that were coming to be known as camp-meeting hymns or spiritual songs. Some of the songs were improvised on the spot, fitting lines from the Bible, references to everyday experiences, and wandering verses and refrains to familiar tunes. Some of the wandering verses and refrains improvised in these new spiritual songs had been printed in Allen’s 1801 and 1818 hymnals. Some were also present in later spirituals.

The songs and performance practices of African Americans at the camp meetings were having an influence on the white participants. Watson writes, "The example has already visibly affected the religious manners of some whites. I have known in some camp meetings, from 50 to 60 people crowd into one tent, after the public devotions had closed, and there continue the whole night, singing tune after tune, (though with occasional episodes of prayer) scarce one of which were in our hymn books."

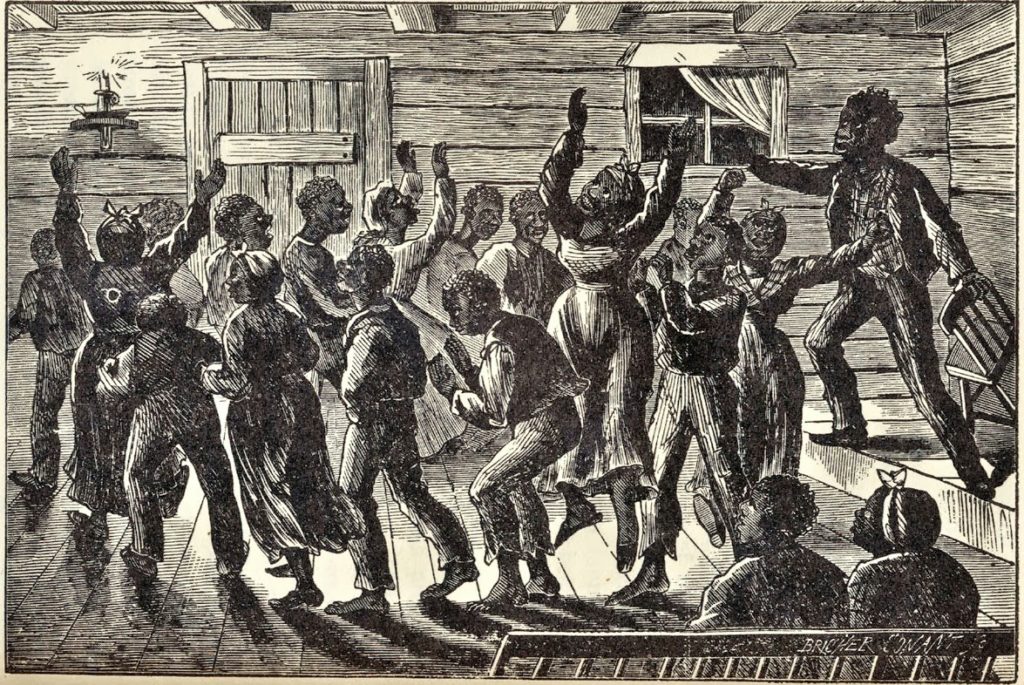

The Ring Shout

Watson also provided the earliest written account of a ceremony of African origin called a ring shout, or shout. A shout is an event in which participants sing a spiritual with strong rhythmic drive while shuffling in a ring formation. Watson observed "With every word so sung, they have a sinking of one or other leg of the body alternately; producing an audible sound of the feet at every step, and as manifest as the steps of actual Negro dancing in Virginia, etc. If some, in the meantime, sit, they strike the sounds alternately on each thigh."

Ring dances were common in many parts of Africa. In the United States, shouts often took place on Sundays or praise nights in the praise house or cabin after the regular meeting was over. They were also seen in New York City markets and in Place Congo, or Congo Square, in New Orleans. Shouts could last four or five hours, with the song taking on the character of a repetitive chant.

"Good Lord (Run Old Jeremiah)" is a ring shout spiritual sung by Joe Washington Brown and Austin Coleman. Folklorists John and Alan Lomax recorded it in 1934 in Jennings, Louisiana, for the Library of Congress.

Spirituals

The improvised religious songs sung by African American Christians at camp meetings, on rural plantations, and in urban churches resulted in a large body of spirituals. Some spirituals were intended to be sung in worship services, others for ring shouts, funerals, or "jes' sittin' around." The word "spiritual" appears to have been commonly used to refer to these songs by the 1860s.

Spirituals were the result of improvisation. A lead singer would sing a line, and others would repeat it or reply with a chorus or refrain. Anyone could interject a new verse. Some lines might be repeated, remembered, and sung the next time. Material from multiple songs or scriptural readings were combined with ideas from personal experiences. Wandering phrases, verses, or refrains appeared in more than one song. The melodies were also born of improvisation, and some tunes might be used for multiple sets of lyrics.

Perhaps the most important element of the spiritual was the performance itself. This was participatory music not intended for an audience. Spirituals demonstrated many characteristics of African music: intense emotion, call and response, polyrhythms, bent notes, blue notes, repetition of rhythmic figures, off-beat phrasings, and body percussion.

Spirituals turned biblical stories into songs. Many centered on faithful servants of God, like Noah, Daniel, and Jonah, who were saved from a sinful world of oppression. One of the most commonly-referenced people in spirituals is Moses. His story of delivering the Israelites from bondage in Egypt resonated with the enslaved African Americans.

“Go Down, Moses” is one of the best-known spirituals. Harriet Tubman said that she used the song to signal that she was nearby and able to help those who wanted to escape. Some slaveholders forbade the singing of it, feeling threatened by the call-and-response message “Let my people go!”

When Israel was in Egypt’s land

Let my people go

Oppressed so hard they could not stand

Let my people go

Coded Messages

Many spirituals conveyed messages that were not as direct as that of "Go Down, Moses." “Steal Away” could be an invitation to escape from bondage. It could also be a call to meet in the woods for a secret meeting to pray or to make plans to run away. Some reports indicate that Nat Turner, who organized a violent uprising of enslaved people, used the song as a call to action.

Steal away, steal away

Steal away to Jesus

Steal away, steal away home

I ain’t got long to stay here

Harriet Tubman used the song “Wade in the Water” to tell escaping slaves to literally put themselves into bodies of water to avoid being seen and to ensure that the slave-catchers’ dogs couldn’t sniff out their scent.

Wade in the water

Wade in the water, children

Wade in the water

God’s gonna trouble the water

The lyrics to spirituals have vivid imagery and symbolic language. Moses represented deliverance from bondage. Egypt and Babylon were the American South. Hell was the Deep South. Slave owners were Pharaoh. The River Jordan was the Ohio River, or any body of water across which lay freedom in the North. The many modes of movement – chariots, wheels, shoes, trains – represented escape.

While spirituals often had these hidden subtexts, they were also beautiful songs of Christian faith, hope, and spirit.

Spirituals in Print

As early as 1800, observers wrote down lyrics to songs they heard enslaved people singing. The first spiritual to be published in print was "Let My People Go. A Song of the 'Contrabands'," a version of "Go Down, Moses." The song was issued in a Northern abolitionist newspaper in December of 1861. It had been learned and written down by the Reverend Lewis C. Lockwood, a missionary to the ex-slaves who took refuge from the Civil War at Fortress Monroe, Virginia.

During the Civil War, three northern abolitionists were educating freedmen on the Sea Islands near Port Royal, a harbor commanding the approach to Charleston, South Carolina. Fascinated by the singing of the newly-freed African Americans, Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware wrote down the texts and notated the music of the songs they heard. They published the songs and their observations in the 1867 book "Slave Songs of the United States." The book was the first published collection of African American plantation songs. It included melodies and text for 136 songs, most of which were spirituals.

The editors acknowledged that it was impossible to capture the nuance of the singing and melodies in printed form. "The voices of the colored people have a peculiar quality that nothing can imitate; and the intonations and delicate variations of even one singer cannot be reproduced on paper. There is no singing in parts, as we understand it, and yet no two appear to be singing the same thing." Nevertheless, since recording technology was not yet developed, “Slave Songs of the United States” provides a vital repertoire and in-depth representation of what spirituals sounded like during the time of slavery.

Spirituals on Stage

In 1866 Fisk University was established in Nashville, Tennessee to educate newly-freed African Americans. Treasurer and music professor George L. White formed a choral ensemble at Fisk that specialized in singing spirituals. White, a white Northerner, arranged the songs in a way that refined them for the concert stage and maintained the essence of their unique power and beauty.

In 1871 the Fisk Jubilee Singers began performing on tour to raise money for the struggling university. In the United States and in Europe, they earned standing ovations and praise from the media. Theodore Seward's song arrangements were published in books and sung by black and white congregations in the North and South. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were instrumental in introducing spirituals to the world. A version of the ensemble is still active today.

Since audio recording technology had not yet been developed by the time slavery ended in the United States, we will never hear the spirituals as they were originally sung. Their sounds can be imagined through songbooks like "Slave Songs of the United States" and descriptions from other contemporary sources. The echoes of spirituals can be heard in the singing of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and the many other artists who have since performed and recorded them. Their pulse can be felt in gospel music, freedom songs of the Civil Rights Movement, blues, jazz, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and hip hop.

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube Playlist

Further Reading

Allen, William Francis, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison, eds. Slave Songs of the United States. New York: Dover Publications, 1995.

Work, John W. American Negro Songs: 230 Folk Songs and Spirituals, Religious and Secular. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1998.

Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Newman, Richard. Go Down, Moses: Celebrating the African-American Spiritual. New York: Clarkson Potter, 1998.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.