Overview

Southern Appalachian square dance is an American hybrid that incorporates elements of dance traditions from a variety of cultures. It is built on a foundation of Scots-Irish reels, and it includes elements of English, French, African American, and Native American dance. Perhaps the most critical innovation, the dance caller, was the result of African American ingenuity.

There are several different types of dance in the Southern Appalachian dance tradition. Step dances, like flatfooting, clogging, and buckdancing, are for individuals. Round dances, like two-steps and waltzes, are for couples. Set dances, like square dances, are for groups of couples. A community dance, or frolic, in Appalachia might include all of these dance forms.

Two types of square dance are part of the set dance tradition. One is a square set which consists of four couples. The other is a circular set that can include any number of couples. Square dances have a visiting-couple structure, which means that each couple takes turns leading the dance figure. The lead couple dances, or visits, with each of the other couples as they work their way counterclockwise around the set.

Southern Square Dance, Pulaski, TN (2014)

Gerald Young, caller

Cultural Diversity in Appalachia

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, folklorists and writers began propagating the myth that the people of the southern portion of the Appalachian Mountain Range (Appalachia) were of pure Anglo-Saxon heritage. This was far from true. The region was home to Algonquian and Cherokee Indians when Europeans began settling there during the 18th century. Scots-Irish, German, English, Welsh, and French settlers came to live in Appalachia. Most of the early settlers followed the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania southwest through Virginia's Shenandoah Valley. Others traveled west from Tidewater Virginia and Charleston, South Carolina.

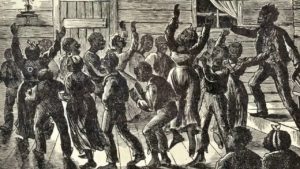

Both free and enslaved African Americans also lived in Appalachia. In the first half of the 19th century, approximately 10 percent of white households owned slaves, typically fewer than five. People in slavery worked in farming, mining, lumbering, riverboats, and hotels. Poor white tenant farmers and sharecroppers often labored alongside enslaved people at work parties, such as corn huskings. They also shared music and dance. Daniel Hundley wrote in 1860 about "industrious poor whites" and slaves in northern Alabama: "And when the long winter evenings have come, you will see blacks and whites sing, and shout, and husk in company, to the music of Ole Virginny reels played on a greasy fiddle by some aged Uncle Edward, whose frosty pow proclaims that he is no longer fit for any more active duty, and whose long skinny fingers are only useful now to put life and mettle into the fingers of the young huskers, by the help of de fiddle and de bow."

The Roots of Square Dance

Southern Appalachian square dance is built on a foundation of circular Scots-Irish reels. The majority of the settlers in the southern mountains were Scots-Irish, and the early frolics that took place there consisted primarily of Scottish and Irish reels and jigs. A reel was not one particular dance. It applied to any number of set dances that had a characteristic weaving movement. Among the early Scottish reels were medieval ring dances, or rounds, which could include many couples. There was also a dance for three dancers called the "Reel for Three" and a variety of four-handed reels for four dancers.

One type of four-handed reel was the Square Four. The Square Four and other four-handed reels were well known in Scotland and Ireland in the early 19th century and became common in Appalachia. Some of the visiting-couple dance figures in the southern square dance most likely originated in the Square Four. Reels for three, four, or five couples were also danced in Scots-Irish communities in 19th century America.

The southern square dance also includes elements of the English country dance. This type of dance became popular in England in the late 16th century. By the end of the 17th century it had spread to France, where the name changed to "contredanse." This name implied its longways formation, which consisted of lines of opposing couples. The French contredanse name was changed to "contra dance" in America. Similar dances by this name can still be found today, especially in New England.

The English country dance was popular in colonial America. John Playford's book The Dancing Master, first published in 1651, included tunes and instructions for 104 dances. In addition to the longways set, formations included "for four," "square dances for eight," and "rounds." Though the English country dance was not widespread in the southern mountains, some of the visiting-couple figures in square dance (Figure Eight, Chase the Rabbit, and Shoot the Owl) likely originated in the English country dance.

A French dance called the cotillion became popular in America in the late 18th century. It was a square dance for four couples. Cotillions largely replaced the English country dance in American ballrooms, perhaps honoring the assistance provided by France in defeating the British during the American Revolution. By the 1820s, a new kind of French square dance, called a quadrille, had become the most popular dance of fashionable society in America. Its popularity spread by flatboat and steamboat, and the earlier Scots-Irish reels came to incorporate its four-couple form.

Dancing was an important part of the culture and religion of Native American societies. These dances were often in a circular ring formation. Sometimes they created a serpentine movement with a dancer leading the line in a spiral coiling into the center, then reversing itself to uncoil. These figures are also part of southern square dance, though it is impossible to determine whether they were inspired by Native American dance or earlier European dances that incorporated similar figures.

Ring dances were also common in African and African American cultures. In these dances, individuals take turns dancing in the center of the ring. This concept became part of southern square dance in the Bird in the Cage figure, which involves a lone dancer in the center of a circle. Perhaps the most significant contribution that African Americans made to the southern square dance is that of the dance caller.

The Square Dance Caller

The European dance forms that preceded the square dance, including Scots-Irish reels, English country dance, and French cotillions and quadrilles, were not prompted by a dance caller. People learned the dances at dancing schools and from itinerant dancing masters. Having the time and money to learn these dances distinguished the middle and upper classes from the lower classes, both in Europe and America. Dancing schools and traveling dancing masters taught the "latest and most fashionable" European dances by the early 18th century in cities and towns throughout colonial America.

African American fiddlers often provided music for dancing schools, masters, and society dances. As they played their instruments, some also learned the dances and figures. Many of these musicians were enslaved and played music at dances for others in slavery. At some point, fiddlers began to call out the figures to English and French dances while the music was being played at plantation frolics. This was the start of the dance calling tradition that is so characteristic of square dancing.

All of the historical accounts of early dance callers, from the mid-18th through early 19th centuries, describe black or mixed-race callers. The fact that these accounts were widespread from New Orleans to New England suggest that the tradition may have begun in the West Indies. Many of the people sold into slavery in North America had been taken from West Africa to work in the Caribbean Islands for "seasoning" prior to entering the mainland.

European Americans were calling dances by the mid-1830s. Published dance manuals began including tips and instructions for calling by the 1850s. This new custom was not received well by all, however. Dancing teacher Charles Durang called it "a vile custom, marring the melody of the airs." Nonetheless, dance calls made the European dances accessible to all, regardless of class or race.

Dance calling was well established in Appalachia by the end of the 19th century. Different styles emerged, with some taking on more rhythmic and rhyming characteristics. Through dance callers, the figures of the Scots-Irish, English, French, Native American, and African American dances converged into the southern square dance.

Square Dance Recordings

Barn dance radio programs gained popularity through the 1920s. These were variety shows that featured the old-time dance music of rural America. When record companies began releasing old-time records in 1923, some of the recordings included dance calls. The calls were generally not timed and sequenced to actually be used to guide a square dance. They were primarily there to provide down-home color to the recordings. Records companies marketed these recordings as "Barn Dances with Calls."

These recordings are a great resource to hear and study regional dance calling styles. The first recordings to include square dance calls were made by banjo player Samantha Bumgarner from Jackson County in Western North Carolina.

There are two African American callers on record from the 1920s: Sam Jones and Jim Baxter. Baxter was an African American-Cherokee guitar player from north Georgia.

Phil Jamison's book Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics provides a complete listing and analysis of the 78-rpm recordings of southern dance callers made from 1924-1933. Some of these recordings are provided in the playlists at the end of this article.

Square Dance Traditions

Dancing was an important social activity throughout the rural South in the 19th century. Dances often took place in homes, with all of the furniture moved out of the largest room. As Harden Taliaferro recalled of dances in Surry County, North Carolina in the 1820s, "As soon as night came, or the work was done, the fiddle sounded, and they danced and courted all night." In the early 20th century, dances moved out of private homes into community spaces such as VFW halls, schoolhouses, and firehouses.

The 1930s saw the rise of the Western square dance. As country musicians moved away from the negative connotations of the mountain hillbilly image, the Western singing cowboy was born and popularized through movies and recordings. Though its roots were in the southern mountains, square dancing became associated with the West.

In the 20th century, people started to promote folk dances, including the square dance, in schools and dance clubs. Their motives ranged from helping to preserve America's cultural heritage to blatantly racist attempts to promote what they perceived as white culture. While the popularity of square dancing has ebbed and flowed through the years, it is an American tradition that is still enjoyed in many communities in the United States.