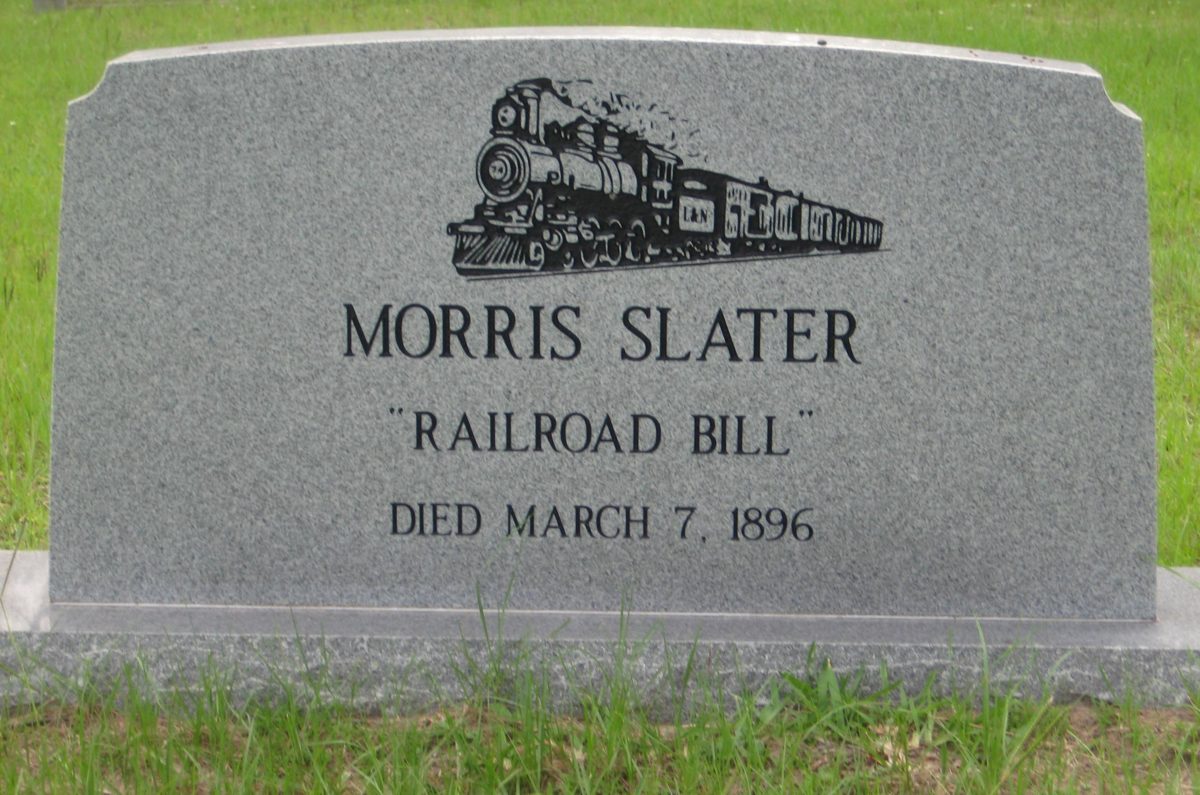

"Railroad Bill" is a blues ballad that dates to the 19th century and has been performed and recorded by many folk artists throughout the 20th century. People have conjectured that the subject of the song is an African American outlaw named Morris Slater who robbed freight trains in the 1890s. Slater's nickname was Railroad Bill. Only a few of the song's dozens of stanzas seem to refer specifically to Slater's activities. The majority of the stanzas are quite general. Was "Railroad Bill" written about Slater? Or did Slater get his nickname from what was a preexisting song, with the verses specific to him being added later?

Historical Background

Stories about Morris Slater began to surface in newspapers in 1895. Slater robbed freight trains, primarily in Alabama and western Florida along the Louisville & Nashville Railroad line. His method was to throw merchandise off moving railroad cars and pick it up later. Slater allegedly killed at least two sheriffs as they, and a succession of detectives and railroad officers, tried to apprehend him. He was shot to death in Tidmore and Ward's General Store in Atmore, Alabama, by Constable McGowan and storekeeper Bob Johns on March 7, 1897.

While most people condemned Slater's crimes, a minority of African Americans in Alabama admired him and turned him into a folk hero. Like the legend of Jesse James, they said he gave the food he stole to poor blacks. Also like the legend of Jesse James, no one has found evidence of this. Some people even attributed supernatural powers to Slater, claiming that he could change form into an animal to escape capture or that he could only be killed by a "solid silver missile."

That Slater could be viewed as a hero and a martyr is not surprising, considering the racial and economic divide in the post-Reconstruction Deep South.

Song History

The song "Railroad Bill" seems to be related to other 19th century songs of African American origin about characters named Bill, including "Roscoe Bill," "Shootin' Bill," and "Buffalo Bill." Some lyrics are shared among these songs. This type of common "floating" stanza is a characteristic of blues ballads and other types of folk songs.

The first lyrics to "Railroad Bill" were collected by folklorists in Mississippi and Alabama during the first two decades of the 20th century. Newman I. White reported three fragments of lyrics he collected from a construction gang in Mississippi in 1906.

Railroad Bill did not know

That Jim McMillan had a forty-fo'

Sheriff Edward S. McMillan of Escambia County, Alabama was killed by Slater while trying to apprehend him. Though the first name in the lyric is different, this stanza may refer to Sheriff McMillan. In "Songs and Rhymes of the South," published in 1912 in the Journal of American Folklore, E.C. Perrow includes a text in which Railroad Bill "killed McMillan like a lightnin' flash."

Howard Odum published three longer texts in his 1911 Journal of American Folklore article "Folk-Song and Folk-Poetry as Found in the Secular Songs of the Southern Negroes." One has no identifiable references to Slater, and one seems to be mostly about him.

The following stanza collected by Odum is very similar to stanzas found in other 19th century Bill songs.

Railroad Bill, Railroad Bill

He never work, an' he never will

It was that bad Railroad Bill

Only four or five of the dozens of "Railroad Bill" stanzas collected and recorded make definite reference to Slater's activities. Especially considering the oddity of a man named Morris Slater being nicknamed Railroad Bill, it is entirely likely that Slater was given the nickname as a reference to a preexisting song or songs. The few verses that specifically reference Slater's activities may have been added later. As with many traditional folk songs, the origins of "Railroad Bill" may never be revealed.

Recordings

The first recording of "Railroad Bill" was made by Riley Puckett and Gid Tanner on September 11, 1924.

Two months later, Roba Stanley and Bill Patterson recorded it. Stanley took out the first copyright on the song, claiming credit for the words and music.

Three recordings of the song were made in 1929, including the first by an African American artist, Will Bennett.

Frank Hutchison's 1929 recording appears to be the first one that was played in fingerpicking style on the guitar. It's also the first with the distinctive Major III chord following the I chord behind the second line of the verse. Both of these attributes became standard in many subsequent versions of the song.

Recordings of "Railroad Bill" are available from many other artists, including Joan Baez, Jerry Garcia, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Hobart Smith, Lonnie Donegan, Crooked Still, Van Morrison, Etta Baker, and Billy Bragg.

Lyrics

Dozens of different stanzas of "Railroad Bill" have appeared in print and on recordings. Below are the complete lyrics from the recordings of Will Bennett and Frank Hutchison.

From Will Bennett (1929):

Railroad Bill, ought to be killed

Never worked, and he never will

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill done took my wife

Threatened to me that he would take my life

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Going upon the mountain, take my stand

Forty-one derringer in my right and left hand

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Going up on the mountain, going out west

Forty-one derringer sticking in my breast

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Buy me a gun just as long as my arm

Kill everybody ever done me wrong

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Buy me a gun with a shiny barrel

Kill somebody 'bout my good-looking gal

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Got a thirty-eight special on a forty-four frame

How in the world can I miss him when I've got dead aim

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

When I went to the doctor, asked him what the matter could be

Said "If you don't stop drinking, son, it'll kill you dead"

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Going to drink my liquor, drink it and win

Doctor said it'd kill me, but he never said when

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

If the river was brandy, and I was a duck

I'd sink to the bottom and I'd never come up

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Honey, honey, do you think I'm mean

Times have caught me living on pork and beans

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Son, you talk about your honey, you ought to see mine

She's humpbacked, bowlegged, crippled and blind

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

Honey, honey, do you think I'm a fool

Think I'm gonna quit you while the weather is cool

Now I'm gonna ride, my Railroad Bill

From Frank Hutchison (1929):

Railroad Bill, got so bad

Stole all the chickens the poor farmers had

Well, it's too bad, Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill, went out west

Shot all the buttons off a brakeman's vest

Well, it's too bad, Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill, got so fine

Shot ninety-nine holes in a shilver shine(?)

Well, it's ride, Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill, standing at the tank

Waiting for the train they call Nancy Hanks

Well, it's ride, Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill, standing at the curve

Gonna rob a mail train but he didn't have the nerve

Well, it's too bad, Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill, he lived on the hill

He never worked or he never will

Well, it's ride, Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill went out west

Shot all the buttons off a brakeman's vest

Well, it's get back, Railroad Bill

YouTube Playlist

Spotify Playlist

Further Reading

Cohen, Norm, and David Cohen. Long Steel Rail: The Railroad in American Folksong. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

“Railroad Bill.” Encyclopedia of Alabama.

http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1258.

“Railroad Bill [Laws I13].” Traditional Ballad Index.

http://www.fresnostate.edu/folklore/ballads/LI13.html.