by David K. Hildebrand

This article, adapted from Kate Van Winkle Keller and Charles Cyril Hendrickson, George Washington, A Biography in Social Dance, is published with the permission of The Colonial Music Institute at George Washington's Mount Vernon. Dr. David Hildebrand is a specialist in early American music. His M.A. and Ph.D. are in musicology from George Washington University and Catholic University. He also teaches American music history at the Peabody Conservatory and writes for the Johns Hopkins University Press.

See also "Southern Appalachian Square Dance: A Brief History"

Contents

Dances of George Washington's Time

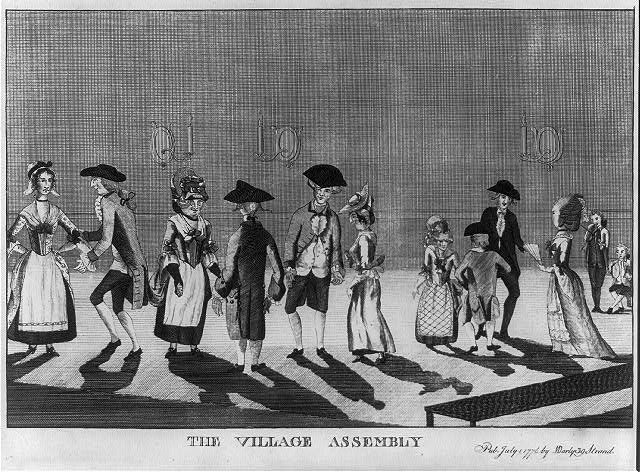

Eighteenth-century social dance is a complex topic. Every occasion where dancing occurred looked different from most others. Important variables that affected the performance were the participants, the on-lookers, the reason for the gathering, the location, the temperature of the room, the hour of the day, and the amount and type of beverages everyone had been drinking. Each of these could change what dance types were selected and how they were actually performed.

A popular country dance might be selected in the spring of 1779 at an officers’ ball hosted by General Greene at the Artillery Park Ballroom in Pluckemin, New Jersey, with music provided by one of the American regimental bands. The same country dance might be chosen six months later in a private room of a ramshackle tavern in Sunbury, Pennsylvania where some of the same officers, a few local merchants, and their families, and a local fiddler might gather, hosted by the innkeeper himself. Patriotic toasts and minuets might open both occasions. The tunes and the figures might be the same, but there the similarities would probably end.

Dancing has always been a public expression of personal abilities. In the eighteenth century, dance events were one of the few venues that brought men and women together in a social setting. There they could publicly display themselves and their families, and solidify friendships that could help with business or political dealings. Since marriages created or continued power dynasties, these dances were important as showcases for eligible partners. On the frontier, dancing after community corn husking certainly helped the romances of young people who spent their days on homesteads far distant from one another.

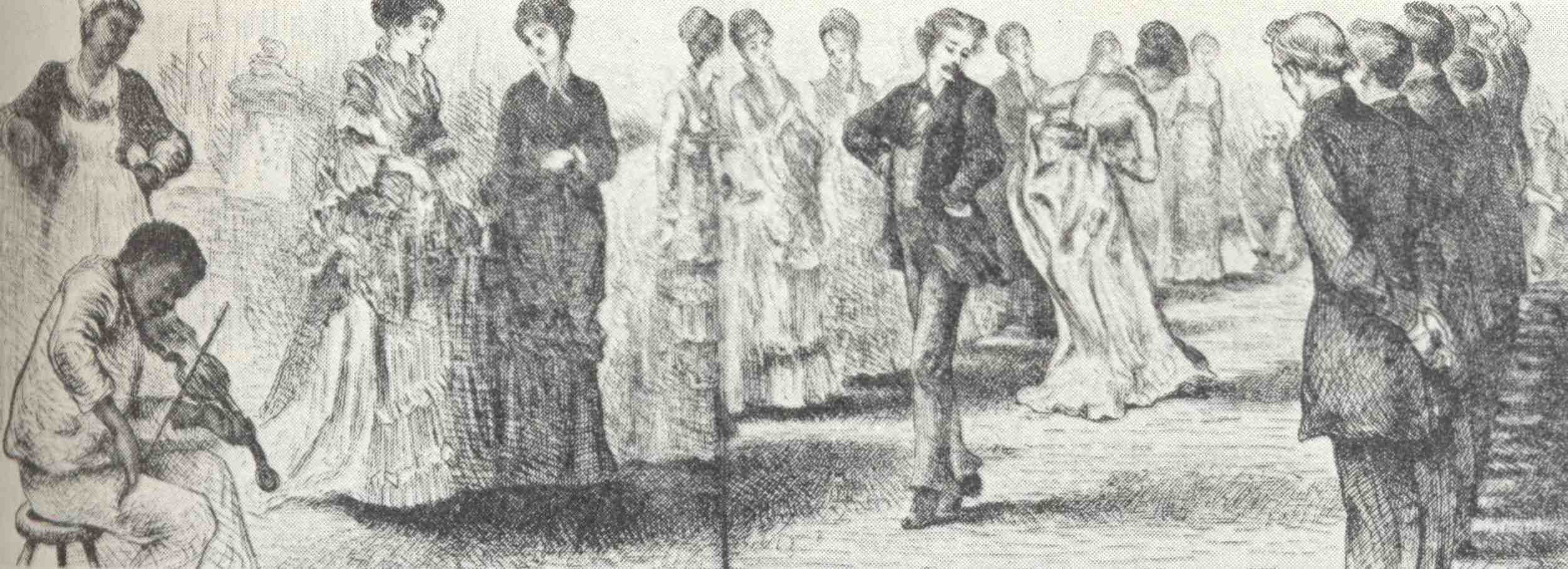

On plantations, African Americans weary from days of toil alone in the fields could gather in groups to relax with dances from their homeland across the sea. It was a chance to reaffirm themselves as a community. In all of these events, the participants enjoyed the pleasure of moving together in time, feeling a sense of oneness with each other, and relishing the physical release from daily pressures and cares. In addition, the musicians, showiest dancers, hosts, managers, and even the caterers gained in status, affecting local balances of power in small but significant ways.

In the century between 1660 and 1760, as the old court-directed society crumbled and the merchant class gained in size and power, the need to establish a social order that all would recognize became urgent. A heavy burden fell on the obtaining and display of consumer goods to define differences. Domestic architecture, clothing, dining customs, and material goods served these functions. In addition, physical demeanor played an increasingly important role. Dance was the art that filled this need, serving the elite well. Instruction in manners, genteel behavior, and movement created visible and portable signs of personal and commercial achievement. Where seventeenth-century sumptuary laws had kept newcomers at bay in the past, a new code of conduct developed that did not require legislation. The test of a gentleman was whether he had the time to absorb the mounting intricacies of taste, grace, fashion, and elegance. The eighteenth-century aesthetic of austerity and nonchalance was considerably harder to emulate than seventeenth-century opulence and bravado.

The “Rules of Civility” that Washington copied out show how real the layers of his society were. In these rules, every social encounter was assessed; participants ranked each other and acted appropriately. As you can see in the rules below, walking and talking with someone in a building or in the street had an etiquette that if mishandled could give insult:

57th In walking up and Down in a house, only with One in Company if he be Greater than yourself, at first give him the Right hand and Stop not till he does and be not the first that turns, and when you do turn let it be with your face towards him, if he be a Man of Great Quality, walk not with him Cheek by Joul but Somewhat behind him.

The depth of a bow was important.

26th In Pulling off your Hat to Persons of Distinction . . . make a Reverence, bowing more or less according to the Custom of the Better Bred, and Quality of the Person.

Frontier and plantation communities were small and tightly knit. Everyone knew everyone else and there was no need to engage in one-ups-man ship. It was in larger population areas that dance came to be used as a badge of membership. Like paper money, gentility was presumed to stand for tangible social assets and was generally accepted at face value. The dance floor was the place where a person’s command of the attributes of gentility: costume, manners, movement grace, and ease, were put to the ultimate and most public test. In 1776, John Adams both acknowledged and decried this display as the “exterior and superficial accomplishments of gentlemen upon which the world has foolishly set so high a value” (Cary Carson 271).

Dance fashions were set by cultivated urban societies as expressions of social status. Enterprising dance professionals devised appropriate movement vehicles to satisfy these needs. Successful dances were promoted as “the latest” or “the most fashionable,” and they displayed the performers to best advantage. Dancing teachers reaped financial gains from the sale of public classes, private lessons, and pre-ball review events. That these lessons and public perception were important is reinforced by William Turner’s advertisement to newly wealthy merchants of Boston in the boom times before the war. In 1774, having just returned from London where he gathered the latest dance fashions, he offered private lessons to “grown gentlemen and ladies, & assures the utmost secrecy shall be kept till they are capable of exhibiting in high taste” (Boston Evening Post May 30, 1774). Tomlinson begins his treatise called The Art of Dancing Explain’d (London, 1735) saying

Let us imagine ourselves, as so many living Pictures drawn by the most excellent Masters, exquisitely designed to afford the utmost Pleasure to the Beholders.

In the eighteenth century, dance was meant to be enjoyed as much by the audience as by the participants. As Cary Carson points out, taste and gentility were sought after and acquired after diligent application and validated only by open demonstration. (Carson 272, 656) Life, in a way, was theater. It needed a setting, props, and an audience, and it was full of aspiring imitators. Rules and standards helped to distinguish the genuine article from the counterfeit.

Main Dance Types

Two dance types, the French minuet and the English country dance, became the staple of eighteenth-century ballrooms in much of the western world, from Moscow to Philadelphia and Mexico City. Ideally suited for performance by dancers of varying skills and abilities, each offered a distinct structure that was fairly easy to learn. Like thorough-bass technique in music, by which fairly simple compositions could be realized in different ways by musicians of varying skills, these dances could be embroidered by their performers to suit their skills and the occasion on which they were being danced. Masters could create new dances every year; composers wrote new tunes. Printers had increasingly cheaper methods by which to reproduce these effusions and the public bought them eagerly.

By 1752, a sufficiently large market had developed that Nicholas Dukes prepared an expensive eighty-three page engraved book with detailed diagrams for the most common country dance figures and the basic figures of the minuet. In his introduction, he explained his purpose.

Though I propose Chiefly to Treat on the different parts of the figuring of Country Dances, yet first of all I will take the Liberty to acquaint every Gentleman or Lady who is desirous of performing Country dances, in a Genteel, free, & easy manner, the necessity they are under of being first duly Qualified in a Minuet; that beautifull dance being so well calculated and adapted as to give room for every person to display all the beauties & Graces of the body which becomes a genteel Carriage. As this dance is the Ground work of all other dancing, I thought it my duty to recommend ye knowledge of it.

Minuet

The menuet ordinaire or ballroom minuet was the chief dance of ceremony and ritual. Devised in the 1660s for the French court, it was a dramatic and powerful dance. Using one of several standard step-sequences and a specific floor pattern, it left some latitude for individualization through ornamentation. Alone on the floor with their concentration on each other and moving with four steps in six beats, two dancers move on a symmetrical track using the entire dance space. Honors to partner and the company open and close the dance. The remainder of the dance consists of parallel passes across the floor and one- and two-hand turns.

The menuet ordinaire or ballroom minuet was the chief dance of ceremony and ritual. Devised in the 1660s for the French court, it was a dramatic and powerful dance. Using one of several standard step-sequences and a specific floor pattern, it left some latitude for individualization through ornamentation. Alone on the floor with their concentration on each other and moving with four steps in six beats, two dancers move on a symmetrical track using the entire dance space. Honors to partner and the company open and close the dance. The remainder of the dance consists of parallel passes across the floor and one- and two-hand turns.

The minuet has a complex basic step, but it is not a string of different steps as in other composed dances like gavottes or allemandes. The challenge of the minuet is the smooth execution with one’s partner, something akin to ice-dancing. It is hard to do so that it looks easy, which, of course, is the desired effect. The minuet became a ritual of the ballroom for the entire eighteenth century. A symbol of precedence and power, the first minuet was performed by the leading man and most important lady present while the rest of the company watched. It served to remind everyone of his or her position within the group. Balls at court often consisted of nothing but minuets as the clamor to be seen attracted more and more dancers.

In America, minuets opened most formal occasions, the Governor, senior military officer, leading merchant, or the host of the event dancing with the most senior ladies present. That the minuet was daunting echoes from account after account of frightened dancers, trembling knees, and laughable performances. It is no wonder that everyone relaxed when the minuets were over and the country dances could begin.

Country Dance

The best-documented group dance of the period is the eighteenth-century version of the English country dance, arranged for “as many couples as will” standing in lines, partner-facing partner. The figures of over 25,000 dances were published with their music in English books between 1700 and 1830 and many more in Ireland and Scotland and Holland. The figures for over 2,800 dances appear in American collections handmade or published between 1730 and 1810. Most of these dances appear to be of English origin or inspiration; several of the collections are direct copies of English books.

Democratic rather than hierarchical, each country dance is constructed so that after one repetition of the figures, the leading couple is in second place and repeats the figures with the next one or two couples. This progression continues down through the entire line and back up, until the leading couple is again at the top and each couple in the set has had a turn leading the dance.

Before 1680, Americans probably danced earlier forms of the English country dance using familiar renaissance steps: the single, the double, and perhaps some steps from the galliard for the more energetic. Once the new French technique was introduced, the basic step became a smooth pas de bourrée, with a demi-coupé for setting and honors. Optional steps included pas de rigaudon (rigadoon), assemblé, balancé, chassé, contretemps, and pas de gavotte (Keller 18–20). For most occasions, deportment and performance style was still formal and presentational. Despite the informal-sounding name, country dances were not undisciplined romps.

At a ball or dancing party, the top couple in the set selected the dance. They not only had to know how the dance figures fit the music, but were responsible for selecting steps appropriate for the abilities of the dancers present, and, by their performance of the first round, the phrasing of steps and figures to the music, a daunting responsibility. Calling the figures as the dance progressed was not an American invention as is often claimed. In 1752 Nicholas Dukes suggests that the top couple might recite the names of the figures when they selected the dance of their choice (Dukes iv).

Public prompting was used in the late 1770s in London by Francis Werner who played on the harp and directed the figures at the same time (Werner title page). It did not become a wide-spread practice until the nineteenth century when the dancers no longer selected the dances to be performed and dance events drew less homogeneous companies.

Cotillion

Several other types of dance appeared in early American ballrooms, promoted by dancing masters to hold their pupils’ interest and by fashionable dancers who wished to keep one step ahead of the crowd. In the 1680s, possibly inspired by the English country dance and using many of the same figures, French dancing masters developed another type of country dance, terming it contredanse. For the next hundred years, as the English longways progressive dance with increasingly simpler figures became the favorite of middle-class ballrooms, the French type developed into a more and more complex, non-progressive dance, usually in closed set formation, suitable for the most elite dancers.

Lacking a clear notation system and, unlike the English country dance, too complicated to transmit in words, these did not become widely fashionable at first. In the 1760s, La Cuisse perfected a system of depicting the figures graphically and these interesting and challenging dances began to appear in print. Almost immediately, English dancers adopted a fairly basic type of French contredanse, the cotillon, anglicized as “cotillion.”

This dance was usually but not always performed in a square of four couples. A cotillion consisted of a number of standard verses called “changes” followed by a chorus that was distinctive to that particular dance. The changes were movements such as circles, hand-turns, hands-across, allemande turns, and rights-and-lefts (chain). The figure, or chorus, was repeated after each change. A cotillion might be performed with as many as eight or ten changes. They employed similar steps to those used in country dances, but usually in more complex combinations, a boon to dancing masters whose services were less needed as the country dances became simpler and simpler to meet the needs of a wider and wider consumer base.

Cotillions were introduced in America in the early 1770s. It is interesting to note that the longways English country dance type has remained in use to the present in New England, having been the fashionable group dance when much of that area was settled. In contrast, the cotillion was at its height of fashion in urban ballrooms between 1780 and 1810, a period during which many European migrants arrived in eastern cities, and many others left for new homes over the mountains. Ironically, it was the cotillion that was carried west and was the basis of traditional American square dancing, recently declared our “national folk dance” and far more associated with cowboy culture than the French ballrooms that gave it birth.

Hornpipes and Jigs

Among other dances in the new French style were those which came to be known as jigs and hornpipes—the names were used interchangeably at this time. These were free-form, display dances for one or two dancers. Early hornpipes were in 3/2, 6/8, or 2/4 meter, but by 1770 most were in 2/4. Such a dance was a personal routine created with step combinations and floor patterns particularly adapted to the skills of the soloist for whom or by whom it was constructed. It could be completely choreographed for a stage or ballroom performance or be entirely a product of personal improvisation, changing every time it was danced.

A hornpipe made famous by Pennsylvanian John Durang, a theatrical dancer active from the early 1780s, survives in a nineteenth-century description. The music and sketchy instructions for the steps were published by his son and employ both cultivated and vernacular dance movements (Durang 158). Durang’s drawings of himself dancing, such as that illustrated here, show that he used standard French techniques such as the foot positions and arms in opposition. Hornpipes and jigs were ubiquitous. All classes of people danced them in all sorts of places, from the opera stage to the back-water tavern, with differing results depending on the time and place. Period images show that routines by sailors in wharf-side pubs were quite different from the dances performed as a “Sailor’s Hornpipe” in professional theaters.

A hornpipe made famous by Pennsylvanian John Durang, a theatrical dancer active from the early 1780s, survives in a nineteenth-century description. The music and sketchy instructions for the steps were published by his son and employ both cultivated and vernacular dance movements (Durang 158). Durang’s drawings of himself dancing, such as that illustrated here, show that he used standard French techniques such as the foot positions and arms in opposition. Hornpipes and jigs were ubiquitous. All classes of people danced them in all sorts of places, from the opera stage to the back-water tavern, with differing results depending on the time and place. Period images show that routines by sailors in wharf-side pubs were quite different from the dances performed as a “Sailor’s Hornpipe” in professional theaters.

One type of impromptu vernacular jig for which descriptions survive had an extremely long and cross-cultural life. It was called a “cut-out jig,” “Virginia jig,” or “Negro jig” in eighteenth-century records and was probably derived from African-American roots. A very similar dance called “Red River Jig” was collected in the 1980s among the Gwich’in Athapaskan Indians who live in the sub-arctic borderlands between Alaska and Canada. This is a step dance performed by one couple on the floor at a time, with everyone else standing as interested spectators and getting ready for their own participation (Mischler 65-69). This same type of dance was observed by the Fletts in Kilberry, Scotland in the 1960s. There the floor would hold many dancers who cut in on one another.

the Everlasting Jig . . . was really a sort of romp. Partners would stand up and jig opposite each other until someone cut in between them. The man or woman displaced had to go off and cut in between another pair. This frolic continued for as long as the piper chose to play (Flett 155).

Samuel Johnson and James Boswell saw a version of this free-form dance on the island of Skye in Scotland in 1773. It is curious that the dance was called “America.”

We had . . . in the evening a great dance. We made out five country squares without sitting down: and then we performed with much alacrity a dance which I suppose the emigration from Skye has occasioned. They call it “America.” A brisk reel is played. The first couple begin, and each sets to one—then each to another—then as they set to the next couple, the second and third couples are setting; and so it goes on till all are set a-going, setting and wheeling round each other, while each is making a tour of all in the dance. It shows how emigration catches till all are set afloat. (Flett 155)

Reels

Another cross-cultural group dance was the Scottish reel, a dance for three or four people in a line. Passages of footwork in place are alternated with traveling on a weaving track. Because of their informal nature, reels were usually impromptu. Little instruction was needed to perform them although they often involved complex individual footwork displaying well-developed personal skills. While simple country dance figures such as circles, hand-turns, and elbow swings may have been danced by the lower classes, the reel was probably the group dance of choice on most occasions. It offered both structure and individual freedom within an improvisational framework.

Allemandes, Gavottes, and Rigadoons

These dances were solos or duets that were choreographed for specific dancers and consisted of individually designed tracks on which the dancer performed combinations of baroque dance steps such as coupé, battement, jeté, pirouette, pas de sissone, and pas tombé. The dances were taught in dancing schools and danced as demonstration or show-off dances in the ballroom or in the theater, but were not group dances. Some of the steps used in these dances, such as the allemande step, rigadoon, and pas de gavotte were occasionally used in social dances, particularly in cotillions.

The Music

Although each of these dance types has a specific name, the music may be called a jig, reel, march, gavotte, hornpipe, allemande, and beginning in the 1790s, waltz. While it might indicate a tune’s origin, the name of the music did not limit its use to any particular kind of dance. In general, rigadoons were usually danced to duple-meter tunes, and minuets were always danced to triple meter tunes. Allemande, minuet, and gavotte tunes were all used for country dances and any lively tune could be used for reels and jigs. The distinction musicians of today make between 2/4 and 6/8 rhythms for reels and jigs did not pertain in the eighteenth century.

Further Reading

Carson, Cary, et al. Of Consuming Interest: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994.

Dukes, Nicholas. A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances, by way of Characters. To which is Prefixed The Figure of the Minuet. London: 1752.

Durang, Charles. The Ballroom Bijou. Philadelphia: 1855.

Durang, John. Memoir. Ed. by Alan S. Downer. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966.

Flett, J. P. & T. M. Traditional Dancing in Scotland. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964.

Keller, Kate Van Winkle Keller. “If the Company can do it!” Technique in Eighteenth-Century American Social Dance. 3rd edition. Sandy Hook: The Hendrickson Group, 1996.

Mishler, Craig. The Crooked Stovepipe. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Werner, Francis. For the Year 1778. Three New Minuets with Seven Favorite Cotillions . . . dedicated to the Nobility and Gentry Subscribers to Almacks &c. By Francis Werner. Where he plays the Cottilons on the Harp and directs the Figures. London: Jold [John] Rutherford, 1778.

* This essay was adapted from Kate Van Winkle Keller and Charles Cyril Hendrickson, George Washington, A Biography in Social Dance (Sandy Hook, CT: The Hendrickson Group, 1998), pp. 18–23