Overview

Cajun music is a distinctive form of American music that blends French Acadian, German, Spanish, African American, Afro-Creole, Scottish, Irish, and English folk traditions. From its roots in 18th-century Acadian music, it developed over generations in southern Louisiana, where people from these cultures interacted. The primary instruments used in traditional Cajun music are the fiddle, accordion, guitar, and triangle, though other instruments may be included. After 1928, Cajun music started to become nationally known through commercial recordings. Exposure to radio, records, and live performances led Cajun musicians to absorb and integrate elements of different forms of American music, resulting in a great deal of variety in Cajun sounds.

The French in North America

Indigenous people first populated the area now called Louisiana approximately 10,000 years before Europeans arrived. The tribes that have lived in this area include the Atakapa, Choctaw, Chitimacha, Houma, Tunia, and Natchez. Though the Spanish were the first European explorers to visit in 1528, the French claimed it in 1682, naming it Louisiana after Louis XIV. The French colony of Louisiana stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada on both sides of the Mississippi River.

In 1604, French settlers led by Pierre du Gua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain established Acadia in present-day Nova Scotia on the border between the United States and Canada. It was the first colony in New France. France and England battled for control of these lands for generations. The Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War) in 1763. It gave Great Britain control over formerly French land in mainland North America except for the territory of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River. In repayment of debt and their alliance in the war, France ceded New Orleans and their western territory to Spain. In 1800, Spain returned Louisiana to France in exchange for territories in Italy.

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Louisiana Territory became part of the United States. Following this, U.S. interests began “Americanizing” New Orleans. This effort was complicated by the arrival of thousands of French refugees, and the people they held in slavery, from Haiti by way of Cuba in 1808. This influx of new arrivals augmented the Francophone (French-speaking) population and made the city much more French than it might otherwise have been. It also introduced musical influences from Cuba.

The Cajun People

The British forcibly expelled approximately 10,000 Acadians from Canada between 1755 and 1763. Most were shipped to England, France, the Caribbean, and the colonies of South Carolina, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. Others escaped to New France, Cape Breton, or into the forests. By 1785, approximately 3,000 Acadians had settled in south Louisiana, still under French rule.

As they adapted to their environment in the swamps and bayous of Louisiana, their French heritage blended with elements of Spanish, African, and Indigenous cultures. The process of creating new cultural forms in this manner is called creolization. The term “Creole” came to identify the people and culture of the region. The word “Cajun” is a creolized version of “Acadian.” The Cajun homeland is a 22-parish region in south Louisiana, known by various names, including Acadiana, Cajun Country, and Bayou Country. Louisiana is divided into 64 parishes, analogous to counties in other states.

Origins of Cajun Music

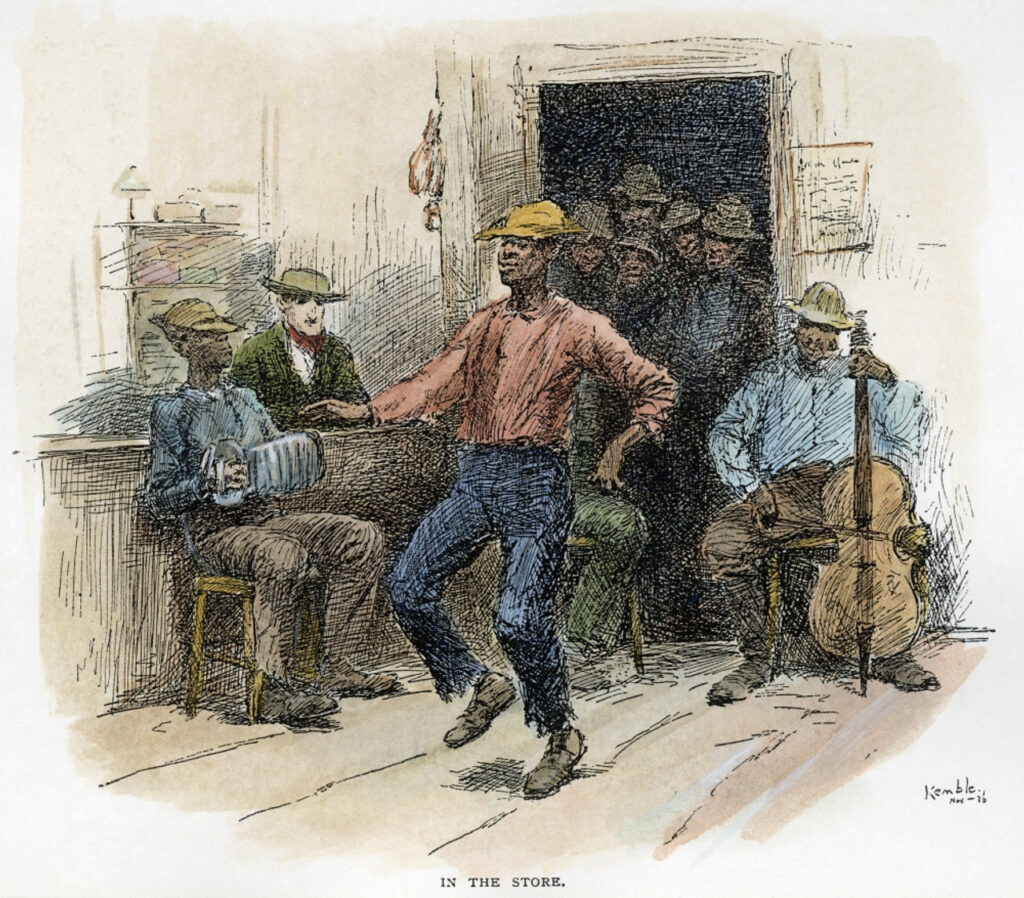

French exiles carried traditional Acadian music with them to Louisiana. These a cappella ballads, drinking songs, laments, chansons rondes, reels á bouche, complaintes, and cantiques formed the foundation of Cajun music. While some Acadians rose to become elite members of the plantation economy, most remained in the working class. These petits habitants, or yeoman farmers, engaged in the neighborhood house dance culture of bals de maison, propelled by fiddle music. Dancing was essential to Acadian life, enabling them to escape daily toil, reinforce social relationships, and court potential romantic partners.

The 19th century brought dramatic change to the area, beginning with President Thomas Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France. This resulted in an influx of Anglo-Americans, shifting the ratio of Francophones to Anglophones (speakers of English) from seven to one in 1803 to three to one in 1812. Following the Civil War, contact with African Americans increased as poor Whites worked alongside Blacks as sharecroppers. Acadian music absorbed qualities of African-American music, including rhythmic syncopation, call-and-response, and highly emotive singing. Dance halls began to replace bals de maison, and both became scenes of frequent violence as the ravages of the postbellum era eroded civility.

Widespread poverty forced many Louisianians to relocate frequently in search of work. Exogamy, or marrying outside one’s social group, became common as Acadians formed families and absorbed the culture of Anglos, Creoles, Italians, and French. In the 1860s and 1870s, Anglophone writers began using terms such as ‘cadien, cagian, cajen, and finally, Cajun, to refer to this mixed cultural group. With increased nationalism and xenophobia, prompted in part by an influx of Irish and German immigrants, Anglos generally viewed Cajuns with contempt or disgust, considering them backward and ignorant.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw Cajun Country increasingly connected with cultural trends of mainstream America. Waterways and railroads brought traveling minstrel, vaudeville, and circus performers to the area. Showboats developed into ornate theaters on the water, delivering minstrel, ragtime, and Broadway songs to patrons along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Phonographs, gramophones, and radios brought mainstream American music to Southern Louisiana.

Cajuns absorbed the latest musical trends and incorporated them into their music. This social music provided entertainment and fueled interaction at weddings, funerals, home performances, house dances, and dance halls. Cajun music continued to evolve as cultural, social, economic, and technological circumstances changed.

Instrumentation

The primary instruments in traditional Cajun music include the fiddle, diatonic button accordion, guitar, and triangle. Documents from the late 18th century referencing music in southern Louisiana indicate that the fiddle and clarinet were common at the time. By the mid-19th century, the fiddle emerged as the dominant instrument. A visiting writer in 1859 documented musicians playing fiddles, mandolins, banjos, and guitars. Guitars grew in popularity throughout the 19th century in Louisiana and elsewhere in the United States. The triangle is a percussion instrument that African-American string bands in the South commonly incorporated before the Civil War.

In the mid-19th century, Cajuns began incorporating the diatonic button accordion, which became central to their music. Austrian inventor Cyril Demian patented the accordion in 1829, though the instrument has various European antecedents inspired by the Chinese free-reed sheng. The accordion and the related concertina spread quickly throughout Europe. German immigrants introduced the instruments to the New World, where musicians incorporated European song styles, including mazurkas and polkas, and adapted the instrument to local musical traditions. The accordion uses the same free-reed technology as the harmonica, which was common throughout the American South by the Civil War. Both instruments produce diatonic chords when air vibrates the reeds – the harmonica by the breath and the accordion by a bellow-button system.

Evidence from contemporary illustrations and travel writers suggests that, in Louisiana, Afro-Creoles may have accepted and incorporated accordions into their music before White musicians. The choppy, syncopated technique evident on early Cajun recordings suggests the African influence, which differed significantly from the smooth European accordion style. White Cajuns and Afro-Creoles purchased these instruments through mail-order catalogs and from shopkeepers who imported them from France and Germany.

As Cajun musicians absorbed influences from mainstream American music after the 1920s, they incorporated additional instruments, including the drum set, upright bass, tenor banjo, and steel guitar played in the Hawaiian lap steel style.

Early Commercial Recordings

The commercialization of Cajun music began during the 19th century when performers started charging to play at house dances and dance halls. Artists, including Joe Falcon, Cleoma Breaux, Dennis McGee, Leo Soileau, Amédé Ardion, and Angelas LeJeune, toured professionally on a regional dance hall circuit.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, record companies developed lucrative niche markets recording the music of minority ethnic groups and selling the records within those communities. In 1920, this expanded to Black blues, gospel, and jazz music, marketed to African-American record buyers in the category of “race records.” White rural music followed, with records of southern string bands and singers performing fiddle tunes, minstrel songs, and popular sentimental songs that were marketed as “hillbilly” or “old-time” music.

Witnessing these trends and the popularity of Cajun music in Louisiana, New Orleans native George Burrow convinced Columbia Record Company to record and release a record by the trio Leon Meche (vocals), Joe Falcon (accordion), and Cleoma Breaux (guitar). In 1928, Columbia released the first 78 rpm record by these artists, “Lafayette (Allon a Luafette),” with only Joseph F. Falcon credited on the label. The record marked the introduction of Cajun music to mainstream America, and it started a wave of Cajun music recordings. Falcon’s recordings were especially beloved in Acadiana, contributing to the accordion's popularity in the region. “Allon a Luafette” means “Let’s Go Lafayette,” in reference to one of the principal cities in Acadiana.

Joseph F. Falcon “Lafayette (Allon a Luafette)" (1928)

Cajun fiddler Leo Soileau began his recording career for Victor in 1928. He was the second Cajun artist to make a record and the first to play Cajun fiddle on a record.

Leo Soileau & Mayuse LaFleur "Mama, Where You At?" (1928)

Phonograph and record retailers in Bayou Country recommended other potential recording artists to Columbia, Brunswick, Victor, Vocalion, Bluebird, Paramount, Okeh, and Decca. These labels released 280 Cajun recordings between 1928 and 1934, demonstrating a wide range of styles and instrumentation. Small dance bands driven by the accordion make up most of these recordings, but companies also released twin fiddle, solo guitar, and harmonica-based records. Song types include one-steps, two-steps, waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, and French interpretations of Anglo-American songs.

Afro-Creoles recorded songs in a blues-inflected Cajun style, beginning with Douglas Bellard and Kirby Riley’s 1929 release of “La Valse de la Prison” b/w “Les Flammes d’Enfer.”

Douglas Bellard and Kirby Riley "La Valse de la Prison" (1929)

“Waxia Special,” recorded in 1929 by accordionist Oscar “Slim” Doucet and guitarist Chester Hawkins, typified the sound of working-class dance bands in Bayou Country.

Oscar "Slim" Doucet "Waxia Special" (1929)

Also in 1929, banjo player Patrick “Dak” Pellerin and pianist Mina Stubbs recorded a French interpretation of the popular American song “Ain’t Misbehavin.” African-American composers Fats Waller and Andy Razaf wrote the song for “Hot Chocolates,” an all-Black review on Broadway starring Louis Armstrong.

Patrick "Dak" Pellerin "Je Jais Pos C Cannye" (Ain't Misbehavin') (1929)

Alcide “Blind Uncle” Gaspard recorded a pair of French ballads for Vocalion in 1929, including “Mercredi Soir Passé” (Last Wednesday Night) and “Assi dans la Fenetre da Ma Chambre.” He sang these accompanied only by his guitar.

Alcide “Blind Uncle” Gaspard “Mercredi Soir Passé” (Last Wednesday Night) (1929)"

Dennis McGee and his brother-in-law Sady Courville were the first to play twin fiddles on record.

Courville and McGee "Courville & McGee Waltz" (1929)

McGee and Afro-Creole accordionist Amédé Ardion provided music for Black and White dances throughout Louisiana. Ardion’s blues-inflected songs and rhythmic syncopation had an immeasurable impact on Cajun music, especially accordion-based songs. Ardion and McGee recorded six sides for Columbia in 1929 and ten for Brunswick in 1930.

Ardion and McGee "Taunt Aline" (1929)

Records by these and other early Cajun recording artists validated marginalized Cajun people, demonstrating that their music had value and was significant enough to stand alongside the heroes of American popular music. The recordings also helped standardize lyrics and arrangements of songs that had been more subject to variations through oral transmission.

Cajun Swing

Industrialization and the flow of American culture into South Louisiana brought changes to the sounds of Cajun music. Through radio, records, and touring artists, Cajun musicians tuned in to urbanized musical genres, including jazz and Western swing, and incorporated the sounds into their music. Cajun swing emerged, exhibiting elements of Western swing filtered through a Cajun perspective. String bands featuring the fiddle became dominant over ensembles that showcased the accordion. Throughout the 1930s, Cajun music became increasingly known outside of Bayou Country.

Western swing from neighboring east Texas blended older rural influences, such as fiddle tunes, cowboy songs, and norteño music of Mexico, with newer urban influences, including jazz, blues, and swing. The growing petroleum industry increased contact between the people of Texas and Louisiana as workers migrated among oil fields in the region. Relations between the people of the two states grew increasingly strained as they competed for the same work opportunities.

By 1935, commercial Cajun music had gravitated to the urban center of Crowley, Louisiana. Crowley was a railroad town that brought a diverse population to the area. Crowley was home to Leo Soileau’s Three Aces (later the Four Aces) and the Hackberry Ramblers, two of Cajun swing’s most popular and influential ensembles. Shifting from older Cajun styles, Soileau formed the Three Aces in 1934 with guitarists Floyd Shreve and Bill Dewey Landry, along with jazz drummer Tony Gonzales. Their sound, sans accordion, helped define the Cajun swing sound. Soileau’s fiddle style and high-pitched, wailing vocals influenced many other musicians.

Leo Soileau and his Three Aces "Hackberry Hop" (1935)

The Hackberry Ramblers formed in 1933 in Hackberry, Louisiana, before relocating to Crowley. Fiddler Luderin Darbone and accordionist Edwin Duhon founded and led the band until Duhon’s death in 2006. The group continues to tour and perform, albeit with different members, as the Riverside Ramblers. They were the first group to use electronic amplification in a dance hall performance. The introduction of amplification in Cajun and other musical forms enabled musicians to develop more nuanced techniques, as they could perform with less physical strain and still be heard in noisy environments.

Hackberry Rambler's "Darbone's Creole Stomp" (1937)

Cajun Honky-Tonk

During World War II, the center of Cajun music migrated to East Orange, Texas, as impoverished Cajuns left Louisiana for work in the oil and wartime industries. This marked a shift from the community’s agrarian values toward a new industrialized world. East Orange was the center of what was emerging as a honky-tonk corridor along the Texas-Louisiana border and northward to Tulsa, Oklahoma. Honky -tonks are dancing and drinking establishments that evolved from the illegal, Prohibition-era speakeasies. Whereas dance halls were generally family spaces, honky-tonks were rougher, adult-oriented establishments that catered to industrial workers with some disposable income.

In this context, honky-tonk music emerged as a subgenre of country music. It featured a strong beat for dancing, electronic amplification to be heard in noisy rooms, and lyrics centered on love, lost love, drinking, and the honky-tonk itself. Cajuns engaged with honky-tonk music through radio, records, and exposure to live acts, and they integrated the style with their musical traditions. Local independent record companies captured these sounds and brought them into the larger landscape of American music. In 1946, J. D. Miller launched the first such record label, Fais Do Do Records, later renamed Feature Records. Miller’s recordings of Lee Sonnier and his Acadian All-Stars included Cajun accordion and honky-tonk’s electric steel guitar.

Lee Sonnier and His Acadian All Stars "Acadian All Star Special" (1952)

Harry Choates’ 1946 recording of “Jole Blon,” generally considered the Cajun national anthem, became a national success through radio and jukebox play. The song's popularity transformed the regional genre into an American musical style. Roughly translated as “Pretty Blonde,” the lyrics refer to a woman who leaves her lover for another man. The melody may be hundreds of years old. The song rose to popularity in Cajun Country in 1929 after Amédé, Orphy, and Cleoma Breaux recorded it as “Ma Blonde Est Parti.” Following this record, dance bands began performing it regularly, and other Cajuns recorded versions. Choates’ recording featured his emotional, wailing vocals and trademark fiddling.

Harry Choates "Jole Blon" (1946)

The musical exchange went both ways as Cajun music came to influence country music. Country music artists, including Red Foley, Hank Snow, Bob Wills, and Roy Acuff, recorded English-language versions of “Jole Blon.” The melody and storyline changed with nearly every version, but the song further integrated Cajun culture into the American mainstream.

Roy Acuff "Jole Blon" (1947)

Singer and electric steel guitar player Julius “Papa Cairo” Lamperez recorded his Cajun composition “Big Texas,” also known as “Grand Texas,” several times in the late 1940s. He recorded the most popular version as a member of Chuck Guillory & His Rhythm Boys.

Chuck Guillory & His Rhythm Boys "Big Texas" (1948)

Honky-tonk star Hank Williams heard the song and wrote “Jambalaya” based on its rhythm and melody. Hank performed frequently throughout the honky-tonk corridor and was much loved in Cajun Country. Through his successful recording of “Jambalaya,” Cajuns increasingly saw themselves as part of mainstream America, though Lamperez was resentful of what he saw as a rip-off of his melody.

Hank Williams "Jambalaya" (1952)

Throughout the 20th century, Cajun music absorbed outside musical influences, evolving into various subgenres. Austin Pitre and the Evangeline Playboys created a biting dance hall sound centered on Pitre’s accordion.

Austin Pitre and His Evangeline Playboys "Bosco Stomp"

Jimmy C. Newman, from Big Mamou, Louisiana, started his career singing country and western. A one-time member of Chuck Guillory’s Rhythm Boys, he later incorporated more Cajun influence into his music. Newman was a long-time star of the Grand Ole Opry and is a member of the Country Music Association’s International Hall of Fame and the Cajun Hall of Fame.

Jimmy C. Newman "Alligator Man" (1961)

In the 1950s, Al Ferrier, nicknamed “The Cajun Rockabilly,” combined Cajun music, country, and the early rock & roll sounds of artists such as Carl Perkins. Al Ferrier & His Boppin’ Billies, Eddie Shuler’s All Star Reveliers, Bee Arnold & the Tune Toppers, and others performed in this Cajun rockabilly style.

Eddie Shuler's All Star Reveliers "Jambalaya Boogie" (1951)

Swamp pop emerged in the 1950s from a blend of Cajun, New Orleans rhythm and blues, and country and western. “Mathilda,” recorded by Cookie and His Cupcakes in 1958, is considered the unofficial swamp pop anthem.

Cookie and His Cupcakes "Mathilda" (1958)

Zydeco is a style of Louisiana French music that diverged significantly from traditional Cajun music. French-speaking Black Creoles imbued this dance music with strong elements of blues, rhythm and blues, soul, Afro-Caribbean, and rock and roll. Accordionist Clifton Chenier was a key architect of zydeco, mixing Cajun French patois with blues tunes and styles in the 1960s. His 1965 recording of “Zydeco Sont Pas Sale” (The Snap Beans Aren’t Salty) popularized the term zydeco, which folklorist Mack McCormick had already used to label the music.

Clifton Chenier "Zydeco Sont Pas Sale" (1965)

Cajun Renaissance

Dewey Balfa, Gladius Thibodeaux, and Louis Vinesse Lejeune appeared at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. Enthusiastic fans during this peak year of the folk music revival responded to them with standing ovations. The performances marked a renewal of interest in traditional Cajun music. Inspired by the response, Balfa returned to Louisiana devoted to preserving and sharing Cajun music. "We were brought up and told that this kind of music's sort of a bastard music," Balfa said. "And you play it for 17,000 people that gives you a standing ovation. It made me realize that no one is better, no music is better than the other music, but then that music is the universal language. It's who you are. I would like to think that I set the fire to the renaissance of Cajun music."

The Balfa Brothers "Parlez Nous a Boire"

Folklorist Barry Jean Ancelet promoted Cajun music and culture by re-establishing the teaching of Cajun French in schools. He co-founded the annual Festivals Acadiens, taught Acadian folklore and culture at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, and hosted a weekly radio program.

Singer/songwriter/fiddler Michael Doucet formed the band BeauSoleil in 1975. Their blend of Cajun music, zydeco, New Orleans jazz, Tex-Mex, country, blues, and rock & roll has made them one of the most successful recent purveyors of traditional and original music rooted in the folk tunes of the Cajuns and Creoles of Louisiana. As of 2024, they are still actively performing.

BeauSoleil "J'ai Ete au Zydeco"

Doucet also performed in a more traditional acoustic Cajun trio with Marc and Ann Savoy in the Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band.

Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band "Quelle Etoile (Which Star)"

The 1984 World’s Fair in New Orleans introduced Cajun and zydeco music to thousands of attendees. The music has also been featured in movie soundtracks, most notably The Big Easy from 1986. Current practitioners, including the Pine Leaf Boys, Lost Bayou Ramblers, Cajun Country Revival, Pays d’en Haut, The Lee Benoit Family Band, and Sarah Savoy (daughter of Marc Savoy), are keeping Cajun music vibrant and contemporary.

Pine Leaf Boys "Pine Leaf Boy Two-Step"

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Further Reading