Contents

- Overview

- Musical Characteristics

- Birth of the Blues

- Blues Queens and Race Records in the 1920s

- Country Blues in the 1920s and 1930s

- Urban Blues in the 1930s and 1940s

- Blues, Rhythm and Blues, and the Birth of Rock & Roll in the 1940s and 1950s

- Blues in the 1960s and Beyond

- Playlists

- Further Reading

Overview

Blues music encompasses a variety of musical styles and has included many different sounds, feelings, moods, and meanings over the years. Musical characteristics of the blues are essential components in other forms of American music, including country, bluegrass, rhythm and blues, rock & roll, funk, soul, and hip hop. Often there is no distinction between blues and these related genres, as elements of the blues are so firmly embedded in them.

The music started taking shape in the American South in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. African Americans incorporated folk forms with roots in West Africa into a new music embodying the freedoms and challenges that accompanied emancipation from slavery. Blues emerged as a hot, new popular music style in 1912 with W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues.” From its rural roots, blues music evolved through the decades and developed into varieties that suited urban environments and changing times.

Musical Characteristics

The melody notes in blues songs provide the music with a distinctive sound and feel. For comparison, first listen to a major diatonic scale, one of the most commonly used scales in Western music.

Major Diatonic Scale

Blues melodies generally build on a different type of scale: a five-note pentatonic scale. This scale can include additional notes and microtones, as singers and instrumentalists bend notes and slide up and down between them. Standard music notation cannot adequately represent these microtones, bends, and slides. Adapted versions of the pentatonic scale have come to be known as “blues scales.” Blues scales include "blue notes,” the flatted third and seventh notes of the major scale, which give the music its characteristic color and feel. African Americans preserved these scales and notes from West African musical traditions.

Blues Scale

Another West African element found in blues is call and response. In African and African American work song traditions, call and response involves a song leader singing or chanting a line, which is either echoed or answered by the group. In blues music, call and response often occurs between a singer and a musical instrument, whether a guitar, piano, or horn.

Many blues songs, but certainly not all, use one of two chord progressions, known as twelve-bar and eight-bar blues. Virtually all subsequent genres of American music use these forms. Songs of any genre are often identified as blues if they incorporate one of these chord progressions or blue notes.

Twelve-bar and eight-bar blues forms may be identifiable, even for nonmusicians. Listen to the example of twelve-bar blues below, specifically the chord changes that occur in bars 5, 7, 9, 10, and 11.

Twelve-Bar Blues Form

The typical vocal pattern that accompanies the twelve-bar form is a single line repeated, followed by a rhyming third line:

I hate to see the evening sun go down

I hate to see the evening sun go down

It makes me think I'm on my last go 'round

Not all blues songs utilize the twelve-bar form or this vocal pattern, but they are both common enough to be worth noting.

Birth of the Blues

Blues evolved in the American South during the second half of the nineteenth century from earlier African American musical expressions, including field hollers, spirituals, shouts, work songs, and dance music. Emancipation from slavery brought new freedoms to African American people, but it came with new challenges, hardships, and sorrows. Early blues music resulted from and embodied these circumstances.

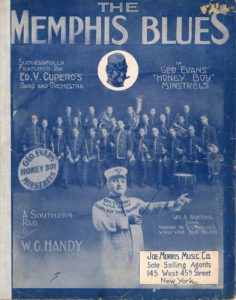

Originally a folk form, the blues became a sensation in the music business. W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues” was a nationwide hit, and it started a blues craze in 1912. Handy, an African American professional bandleader and songwriter, incorporated aspects of the folk blues he heard in the South into “Memphis Blues” and his other compositions.

Morton Harvey: "Memphis Blues" (1914) - the first blues song sung on record

For the remainder of the decade, publishers and record companies released a string of blues hits on sheet music and phonograph recordings, and dance bands played them nationwide. Although originating with African American musicians, many of the published compositions and all the records were by white, professional songwriters, vaudeville singers, and dance orchestras.

See Birth of the Blues for more.

Blues Queens and Race Records in the 1920s

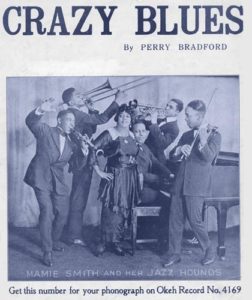

In 1920, OKeh Records released the first blues song recorded by an African American singer. Defying the industry’s expectations, Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” was one of the best-selling records of the year.

Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds: "Crazy Blues" (1920)

The success of “Crazy Blues” prompted companies to realize that a market existed for records by African American musicians. Labels recorded many other successful “blues queens” throughout the decade, including vaudeville singers Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Edith Wilson, and blues specialists Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, Ida Cox, and Ma Rainey. These singers wore glitzy costumes and performed with pianists or small jazz ensembles. Some refer to this style as “classic blues.”

Record companies promoted and sold these records as part of dedicated “race records” series, targeting black record buyers with blues, jazz, gospel, and comedy recordings by black artists.

See Blues Queens and Race Records in the 1920s for more.

Country Blues in the 1920s and 1930s

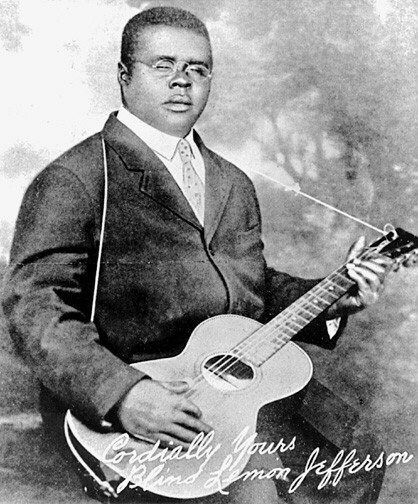

In 1926, Paramount Records recorded a Texas street singer and guitarist named Blind Lemon Jefferson. His records were a runaway success.

Blind Lemon Jefferson: "See That My Grave is Kept Clean" (1927)

Jefferson’s popularity started a wave of country, or rural, blues records. These were primarily solo singers who performed their own compositions and accompanied themselves on acoustic guitar, sometimes with other sparse instrumentation. Many people believe that country blues represents the original blues music as it existed in the South before taking shape as popular music in 1912. However, rural blues recordings of the late 1920s capture professional musicians who heard more than ten years of published and recorded popular blues music. The influence between these styles likely went both ways.

While most country blues artists did not reach the levels of professional success of the blues queens, their records sold well between 1926 and the start of the Great Depression in late 1929. They also influenced other genres of American music, most notably country and rock & roll. Country blues artists from the 1920s and 1930s include Charley Patton, Son House, the Mississippi Sheiks, Blind Blake, Blind Willie McTell, and Robert Johnson.

Johnson was in the generation of blues artists that followed the first recorded Delta singers, which included Charley Patton and Tommy Johnson. Robert Johnson’s recordings from 1936 and 1937 integrated elements from the older bluesmen with the sophisticated urban blues styles that developed in the 1930s.

Robert Johnson: "Me and the Devil Blues" (1937)

Urban Blues in the 1930s and 1940s

Around 1916, Southern African Americans started migrating in large numbers to urban centers, including Chicago, New York City, St. Louis, Detroit, and Los Angeles. Black musicians brought blues music with them, and they adapted the sounds to fit their new, urban environments. Guitarists transitioned to electric instruments, so patrons in noisy bars, restaurants, and rent parties could hear them. Pianists played repetitive boogie-woogie bass note patterns that drove the dance rhythms coming out of jukeboxes.

Albert Ammons: "Boogie Woogie Stomp" (1936)

Popular blues styles in the 1930s included blues crooning, hokum, and big band swing. The first big hit of the relaxed, crooning style was “How Long, Low Long Blues,” recorded by singer and pianist Leroy Carr and guitarist Scrapper Blackwell for Vocalion in 1928.

Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell: "How Long, How Long Blues (1928)

Hokum blues was upbeat, party music with humorous lyrics rich in sexual analogies and innuendo. Popular titles included “Banana in Your Fruitbasket” and “Let Me Play with Yo’ Yo-Yo.” “It’s Tight Like That,” by the guitar and piano duo of Tampa Red and Georgia Tom, set off this wave in 1928.

Tampa Red and Georgia Tom: "It's Tight Like That" (1928)

From the mid-1930s through the mid-1940s, big band swing music dominated the popular music landscape in the United States. Swing was an incarnation of jazz music that emphasized song arrangements and orchestrations focused on sections of instruments, which included trumpets, trombones, saxophones, and rhythm (piano, guitar, bass, and drums). Many swing hits were blues songs built on blues scales or the standard twelve- and eight-bar forms.

The Count Basie Orchestra: "One O'Clock Jump" (1937)

The constrictions in human, material, and financial resources that came with the United States’ entry into World War II resulted in the rise of small-group jazz and blues. Jump blues groups stripped big bands down to a rhythm section, just two or three horns, and a singer. Stars of this genre included Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five, Big Joe Turner, and Louis Prima.

Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five: "Choo Choo Ch'Boogie" (1946)

Los Angeles produced a sophisticated blues sound that featured crooning vocals and increased prominence of electric guitar. Nat King Cole, Charles Brown, Amos Milburn, and T-Bone Walker exemplified this sound. T-Bone Walker’s guitar playing and showmanship influenced countless guitar players from blues to rock & roll.

T-Bone Walker: "Mean Old World" (1942)

Blues, Rhythm and Blues, and the Birth of Rock & Roll in the 1940s and 1950s

Chicago attracted many migrants from the Mississippi Delta, and the city became a center for blues music in the 1930s. McKinley Morganfield, better known as Muddy Waters, moved to Chicago in 1943 to pursue a career as a musician. He started playing his Delta blues songs on electric guitar and added drums, bass, piano, and amplified harmonica. It was a rawer, grittier sound than West Coast and jump blues. Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, and Jimmy Rogers were among the musicians who defined the Chicago blues sound in the 1950s.

Muddy Waters: "Walkin' Thru The Park" (1959)

In 1949, Billboard magazine gave their Race Records chart a new name – Rhythm and Blues. The chart still tracked the popularity of records by black artists in a variety of genres, but in the late 1940s, the term was coming to define a distinct style of music. The contemporary blues sounds coming out of urban centers were beginning to be called rhythm and blues.

Among the rhythm and blues artists, New Orleans pianists Fats Domino and Professor Longhair flavored boogie-woogie and West Coast blues styles with the Caribbean rhythms of the city.

Fats Domino: "The Fat Man" (1949)

In Sun Studio in Memphis, blues and rhythm and blues artists, including Rosco Gordon, Ike Turner, Little Milton, and B.B. King made their first recordings. King, who was born on a cotton plantation in the Mississippi Delta, had a long and successful career that moved easily between blues, rhythm and blues, and, later, soul, which added gospel inflections.

B.B. King: "How Blue Can You Get?" (1971)

The rhythm and blues genre also included vocal harmony groups that were emerging from the streets of Baltimore, Washington, D.C. New York City, Philadelphia, and other urban centers. These quartets or quintets of African American male singers fused Tin Pan Alley standards and sentimental pop songs with blues material and energy.

The Clovers: "Fool, Fool, Fool" (1951)

In the early 1950s, the music industry started re-branding rhythm and blues as rock & roll. White teenagers were increasingly listening to rhythm and blues on the radio and buying the records, which challenged societal norms of segregation. The term rock & roll was an attempt to make rhythm and blues more acceptable to mainstream America.

To sell to more white customers, record companies also released cover versions of songs originally recorded by African American artists. Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll” reached #1 on Billboard’s Rhythm and Blues chart and peaked at #22 on the popular music chart in 1954. Bill Haley & His Comets’ cover version was released four months later and reached #7 on the popular music chart.

Big Joe Turner: "Shake, Rattle and Roll" (1954)

Blues in the 1960s and Beyond

By the early 1960s, interest in folk music was growing among young adults, inspired by the 1953 release of The Anthology of American Folk Music and the success of the Kingston Trio and other contemporary folk artists. The folk music revival included a renewed interest in the older country blues styles. Still-living country blues artists who first recorded in the 1920s and 1930s, including Mississippi John Hurt and Son House, enjoyed success performing at folk festivals, in coffeehouses, and on college campuses. The revival also inspired a new generation of young acoustic-blues-based performers, including Dave Van Ronk, Jim Kswekin, and Koerner, Ray, and Glover.

Dave Van Ronk: "Stackerlee" (1962)

During the 1960s, the blues genre further branched out into soul, funk, and blues rock. A wave of British artists, inspired by American blues and rhythm and blues of the 1950s and a reissue of Robert Johnson’s recordings, became popular in the United States with blends of blues and rock. These artists include the Rolling Stones, the Animals, Cream, John Mayall, and the Yardbirds. American artists in this field include Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Canned Heat, and Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band: "Blues with a Feeling" (1965)

Since the 1960s, electric and acoustic blues performers have carried on traditions, pushed the blues in new directions, and developed loyal followings. Acoustic performers include Guy Davis, Rory Block, Corey Harris, and Paul Geremia.

Rory Block: "Tallahatchie Blues" (1995)

Electric blues artists include Robert Cray, Bonnie Raitt, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Johnny Winter, and Joe Bonamassa.

Beth Hart and Joe Bonamassa: "I'd Rather Go Blind" (2011)

Blues stands as the trunk of the American music tree. It grew from the roots of older, primarily African American, elements and branched into virtually every form of American music. There is a strong blues presence in jazz, rock, country, bluegrass, rhythm and blues, soul, funk, and hip-hop music to this day. The sounds, styles, meanings, and instruments have changed through the years, but blues remains fundamental to America’s music.

Playlists

Apple Music

Spotify

YouTube

Further Reading

Crawford, Richard. America’s Musical Life: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Gioia, Ted. Delta Blues: The Life and Times of the Mississippi Masters Who Revolutionized American Music, 2009.

Jones, Leroi. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Harper Perennial, 1999.

Miller, Karl Hagstrom. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Milward, John. Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock ’n’ Roll. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2013.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Wald, Elijah. Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. New York: Amistad, 2004.

Wald, Elijah. The Blues: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.